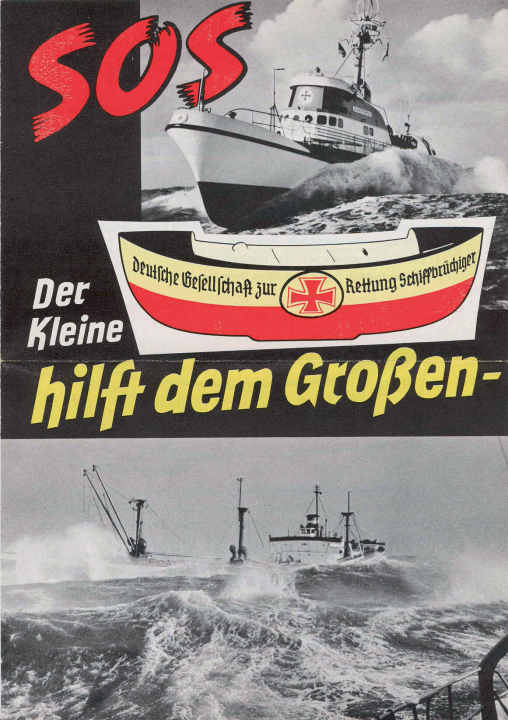

With cork waistcoats on the rowing boat and rowing off: This is how sea rescue began on German coasts 160 years ago. Whether bakers, blacksmiths or the occasional fisherman on watch, they battled the stormy seas to help their neighbours in distress. They were equipped with courage, determination and local knowledge of the area.

If today a Dinghy driver overboard a boater is in urgent need of medical assistance, on the Baltic Sea a boat drifting along rudderlesst or tanker is on fire, an emergency call is made to the Bremen Maritime Rescue Centre. A coordinated search and rescue operation is then launched. Around 1,000 sea rescuers, including around 800 volunteers, are always on standby with 60 rescue cruisers and boats at 54 stations from Borkum in the west to Ueckermünde in the east.

Challenging assignments and training that packs a punch

Every year, sea rescuers are deployed around 2,000 times. It is not uncommon for them to risk their own lives in the process. To minimise the risks as much as possible, they need state-of-the-art technology and extremely seaworthy, high-performance ships. But also the training of sea rescuers is a tough one: before they are sent out on their first mission, they undergo a demanding training programme. They have to be familiar with complex manoeuvres, navigation electronics, engines, rescue equipment, first aid and, without fail, the special features of the local area.

The careers of rescue workers can be very different. Some have many years behind them as seafarers, on the world's oceans in cargo transport or as fishermen on the coast. Others are recreational skippers or completely inexperienced in seafaring. But they have one thing in common: they want to rescue people from distress at sea and have proven themselves to be team players and reliable - these are some of the most important personal requirements for this job.

Since 2019, the DGzRS has bundled all of its training and further education programmes under the umbrella of the Maritime Search and Rescue Academy. This is based on four pillars and is based at various locations: at the sea rescue stations along the North Sea and Baltic Sea coasts, at the simulator centre in Bremen and at the sea rescue training centre in Neustadt, including a training fleet attached to it.

In ship safety courses, they practise leak defence, firefighting and abseiling from helicopters. These courses have to be repeated regularly - they can be life insurance for the rescuers. Regular training also takes place at the stations themselves, such as towing large ships with comparatively small lifeboats - a demanding and not without danger manoeuvre.

The floating classroom comes to the volunteers

More than 800 volunteer sea rescuers are on constant standby on the North Sea and Baltic Sea. On the Training ship "Carlo Schneider" they train for emergencies directly on site. The 22-metre-long training ship travels along the German coast and enables the sea rescuers to train directly in their operational area. "The sea rescue service requires lifelong learning," explains trainer Thomas Baumgärtel. With the "floating classroom" concept, the 800 or so volunteer sea rescuers do not have to travel to training courses, but can practise in their own area. "This is a huge advantage for our volunteers when we come to their homes," emphasises Baumgärtel. "On the one hand, they don't have to take time off work and travel, and on the other hand, they practise in their own area, where they will also go out in an emergency."

The training programme on the "Carlo Schneider" includes a wide range of exercises. In addition to towing, line handovers in swell and communication with casualties are also trained. "You must never forget the psychology of the moment," explains Baumgärtel. "Many casualties are overwhelmed and frightened. Our job is to exude calm and safety and to give them precise and clear instructions." The training sessions therefore take place under different conditions. While calm harbour basins offer ideal conditions for initial exercises, the manoeuvres are later carried out in freshening winds and swells. This allows the sea rescuers to internalise the procedures and act safely even in stressful situations.

The training vessel was specially designed for training purposes. It has a modern training room and is equipped with the same engines that are used in the 10.1 metre sea rescue boats. This means that the volunteers can also receive technical training and further training. "In the past, you could rely more on skilled seafarers," explains Baumgärtel. "Today, there are fewer and fewer people in Germany who come from a seafaring background and have the relevant experience."

Norddeich Radio" became the Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centre (MRCC)

The DGzRS is responsible for the maritime search and rescue service in the event of an emergency at sea, the so-called SAR service (Search and Rescue). The coastal radio station "Norddeich Radio" played an important role in this for over 90 years. It went into operation on 1 April 1907, heralding a new era of maritime communication. With the constant monitoring of the 500 kHz maritime distress frequency from 1936, Norddeich Radio became indispensable for the safety of shipping. In the post-war years, the coastal radio station continuously expanded its range of services, broadcasting nautical warning messages on medium and border waves and conducting radio medical (medico) calls, which enabled medical assistance at sea.

However, advancing digitalisation and new communication technologies heralded the end of Norddeich Radio. At the turn of the year 1998, the MRCC Bremen of the DGzRS took over the VHF call channels 16 (analogue) and 70 (digital). Norddeich Radio thus ceased its VHF maritime radio service and the legendary DAN call sign fell silent forever. Since then, the Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centre (MRCC) Bremen, operated by the DGzRS, has acted as the German maritime rescue coordination centre and coordinates all measures in accordance with internationally binding standards. This centralised coordination is crucial for the efficiency of rescue operations, as this is where all the information comes together and resources can be optimally deployed. In addition, the MRCC Bremen monitors the globally standardised emergency radio frequencies in order to be able to receive international calls for help.

Best rescue fleet: the collection ships

Although the DGzRS fulfils a task assigned to it by the federal government with its SAR (Search and Rescue) service, it has retained its independence and is financed exclusively by voluntary donations. The collection vessels also make a significant contribution to this. The smallest members of the sea rescue fleet are also celebrating their birthday this year: the mini-model lifeboats have been standing on counters in pubs, shops and passenger ships for 150 years and are also missing from small pleasure craft tests. They literally have it all: every year, they contribute up to 900,000 euros to the sea rescuers' budget. There are around 14,000 collection boats throughout Germany.

The DGzRS's "register of ships" lists an impressive variety of berths for the collection ships. Some are travelling "piggyback" on the training sailing ship "Alexander von Humboldt II" or on large Hapag-Lloyd container ships across the world's oceans. Particularly unusual: one collection ship is even travelling underwater on a German Navy submarine. One reached the North Pole with the research icebreaker "Polarstern", while another is anchored in the Antarctic on the research station "Neumayer III", where it functions as a "phrase pig".

The collection boats can also be found in remarkable places on land. The 50,000th one was placed on the Zugspitze in 1996 by actor Wolfgang Fierek, almost 3,000 metres above sea level. Singer and DGzRS ambassador Reinhard Mey placed the 55,000th collection boat four years later on the Berlin television tower, Germany's tallest building. Deep underground, one can be found in the UNESCO World Heritage Rammelsberg mine in the Harz Mountains, while another is located in the nearby Brocken Hotel at an altitude of over 1,100 metres.