- Different VAT rates

- Illegal import can result in a fine

- Not only buyers, but also owners affected

- Tax already paid on purchase 15 years ago

- EU Community status lost

- State cashes in several times

- Chained up in France

- Lower tax rate in the overseas departments

- Some countries handle tax issues more laxly

- EU tax rules are a barrier to trade for yacht brokers

- Tax dispute has landed at French ministry

Anyone importing a motorboat that has been based in an EU member state for a long time or never before into Germany or another EU country must expect a visit from customs when entering the country. This is because, by law, VAT is almost always due on the boat. This can quickly become expensive. However, the tax is apparently not collected everywhere. In some countries, however, it is, as a recent case shows.

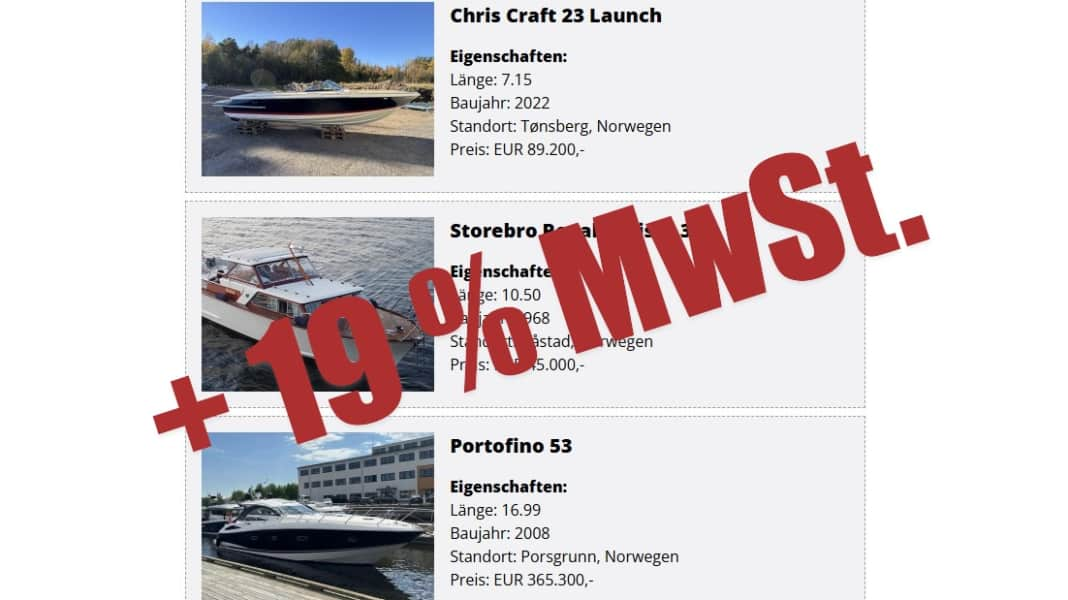

Anyone looking for their next dream boat on second-hand boat exchanges sometimes comes across offers, particularly from non-EU countries, that seem surprisingly lucrative. At least at first glance. However, if you take a closer look, it is not uncommon to see indications such as "ex VAT", "export price" or simply "net" behind the price.

The reason: sellers in the countries concerned are hoping to attract potential buyers from abroad. In Norway, VAT is 25 per cent, in Montenegro 21 per cent and in Turkey 20 per cent. Without this tax surcharge, the boat price looks much more favourable.

Different VAT rates

And it is actually an advantage in such cases if, for example, only 19 per cent VAT is payable on the purchase price in Germany. The problem is that not every used boat buyer in Germany has this in mind.

In the Lake Constance region in particular, customs often catch owners who have bought their boat in neighbouring Switzerland (not an EU country) and then brought it to Germany (EU country) by sea or land without worrying about customs or VAT.

Illegal import can result in a fine

Both must then be paid retrospectively. And there may also be a fine for the tax offence. Only if a used boat is purchased in an EU country and the VAT has usually already been paid by the first owner can the VAT issue be ignored. It will not be charged a second time. However: exceptions prove the rule!

In one case, the tax authorities of the EU member states do hold out their hand a second time. This is when a boat from a non-EU country, but which originally comes from the EU and for which VAT was also paid in the EU by the first owner, is now brought back into the EU. The three-year rule then applies: if the boat has been outside the EU for longer, the tax is due again upon importation. Reasoning: After this period, exported goods lose their EU Community status.

Not only buyers, but also owners affected

Incidentally, this not only affects second-hand boat buyers, but also owners who have had their boat moored in a non-EU country for more than three years. For example, in Montenegro or Turkey. They will also have to pay VAT again when travelling to Greece or Croatia, for example.

But not always. It often depends on the customs and tax authorities of the EU countries whether they actually charge the owner the VAT that is actually due. This is illustrated by the recent case of a Belgian who first travelled to Spain and then France with his yacht purchased in the Caribbean.

Stéphane Dubois now sees himself (Name changed by the editors) was confronted with hefty tax demands from the French tax authorities. They are demanding several tens of thousands of euros in VAT from him, which is to be paid to the French treasury for his ship. However, VAT had already been paid on Dubois' yacht in France many years ago.

Tax already paid on purchase 15 years ago

The problem: the ship, a 19-metre blue water yacht from the French Garcia shipyard, had been sailing around the world with the first owners in recent years. They had bought the boat new in 2010 and also paid VAT in France as part of the purchase. Two years later, they left EU waters and set off on their long voyage. This lasted until 2016, when they headed for Martinique and ended their round-the-world trip there.

In the years that followed, the ship remained in the Caribbean state - apart from individual trips and repair stops on neighbouring islands. A special feature in this context: Martinique is a French overseas department and is therefore part of the EU.

Two years ago, Stéphane Dubois discovered the circumnavigator's yacht, which had since been put up for sale, and struck. He brought the ship back across the Atlantic to Europe. His first port of call in the EU was Baiona in Spain. He cleared in there. Spanish customs inspected the ship and confirmed that it had entered the EU. The officials did not mention the VAT that was automatically due in Spain.

EU Community status lost

Dubois continued his voyage without a care in the world. Next harbour: La Rochelle in France. Customs came on board there too - and to the owner's surprise, issued a hefty tax assessment. To determine the tax amount, they used the current value of the ship as a basis. The customs officers calculated this on the basis of the purchase price that Dubois had just paid to the previous owners.

"As the ship had been outside EU waters for more than three years without interruption during its circumnavigation with the first owners, it had lost its status as a Community good under EU-wide tax regulations," explains Dubois. "This means it is treated by customs in the same way as any other goods imported into the EU from outside."

State cashes in several times

This means that VAT is levied in addition to customs duty. The amount depends on the value of the goods and the tax rate of the EU country to which the goods are first imported or for which they are destined.

Whether VAT has already been paid in the EU in the past, as in the case of Garcia, is irrelevant. "But that's just one aspect of the matter that I find unfair. Because even if I pay the tax again now, the first owners won't get back the tax they paid in 2010," explains Dubois. "So in the end, the state collects twice for the same product!"

Chained up in France

Incidentally, formally speaking, it is not VAT that is charged on the import of goods, but import VAT. However, the same tax rate applies to both.

What also annoys the Belgian: "Other countries turn a blind eye if the three-year period is exceeded by up to six months and then do not deny the ship its Community goods character. According to the previous owner's logbooks, my Garcia was outside EU waters for three years and five months, and yet the French tax authorities are now insisting on taxing it," complains Dubois.

When he arrived with the ship in La Rochelle in 2023, customs had put it on a chain. I had to pay a security deposit in the amount of the tax. Only when that was done was I allowed to continue sailing," reports the Belgian. He has been contesting the tax assessment ever since. So far with moderate success.

Lower tax rate in the overseas departments

After all, the authorities are probably prepared to deduct the tax that was theoretically already due when the ship entered Martinique in 2016. Actually a great concession. In Martinique, as in all overseas departments of France, a very low VAT rate of 8.5 per cent applies. This leaves "only" 11.5 percentage points difference to the French tax rate of 20 per cent.

However, there are several catches: the overseas departments are not officially part of the EU tax territory. This type of differential taxation, which France applies, is therefore not anchored anywhere in EU tax law. With regard to the Garcia, the next EU country to which the yacht travels could therefore object to the French differential taxation and correct it to the detriment of Stéphane Dubois.

Some countries handle tax issues more laxly

But even more problematic: the first owners had apparently not paid any import tax when they arrived in Martinique in 2016. As was later the case in Spain, the authorities there had probably waived it or simply failed to collect it.

"The EU has forgotten to take the specific needs of recreational boating into account in its tax legislation," says Stéphane Dubois with annoyance. He calls on the local maritime associations to urge politicians to address the problem. "You can't equate a ship that is used for living and travelling with just any other product that is imported into the EU."

EU tax rules are a barrier to trade for yacht brokers

Jean-Paul Bahuaud shares this view. He has been selling second-hand yachts in Guadeloupe for many years. This Caribbean island is also a French department. "Many of our customers who buy a boat here and want to bring it back to Europe get into trouble with customs." Bahuaud is in favour of changing the status of the overseas departments as quickly as possible and extending the EU tax territory to them.

"Otherwise, it is left to chance whether or not you will be asked to pay when re-importing a ship into EU waters," says the yacht broker. Countries such as Spain and Portugal are known for not caring about the issue. Other countries, on the other hand, are known for their rigid approach. In the past, this included Italy in particular. Now France is apparently also keen to relentlessly collect tax debts from yachtsmen.

Tax dispute has landed at French ministry

Stéphane Dubois definitely wants to continue fighting for what he sees as more tax justice for boat buyers and long-distance travellers, as well as for an end to the uncertainty about what sailors will face when they return to the EU. After all, for many long-distance returnees in particular, the yacht is often the only asset they own after years away. They often lack the means to cope with a high tax demand.

Dubois: "My case is now with the arbitration centre of the French Ministry of Economy and Finance. I hope that they will be sympathetic to us sailors."

Pascal Schürmann

Editor YACHT