Why the hell do they have a nine metre high mast on their rib? That's the first question I ask myself when I visit the base of the SP-80 team in Leucate, France. Two 300 hp engines at the back and then this carbon fibre mast in the middle of the dinghy? The solution to the riddle also reveals the speciality of the Swiss team: the huge kite is attached to the mast out at sea on the record course. This is because the team's trimaran is not powered by a classic rig with conventional sails, but by the very sports equipment that kiteboarders - nomen est omen - usually use.

Mayeul van den Brock, team leader and helmsman of the SP 80, smiles when he notices my gaze. "Benoit and I drive the boat, but ultimately we need eight people on the water to be able to launch." He explains that the size of the kite varies depending on the wind strength. It can be between 12 and 40 square metres in size. The team rigs it up, attaches it to the mast, lets it rise and finally hands it over to the tri. His co-pilot Benoit Gaudiot then slowly brings the kite "into the zone" with the help of four steering ropes, which he controls using a wheel and a lever. This is the area in which the profile of the kite generates optimum propulsion.

This might also interest you:

And then it starts! So far, after several tests, they have achieved a speed of just over 43 knots. In the upcoming races, they want to break the 50-knot mark. The goal is 80 knots, hence the team name. "Paul Larsen still holds the speed record under sail at 65.45 knots. So we have to aim for the 80 knot mark," says Mayeul. He says that they are in close contact with the record holder and have already met several times. Larsen wished them luck and gave the team an autographed picture of his first record run.

Mayeul: "He is a real inspiration and takes a sporting view of our endeavour. If we break his record, he will try to get it back." The record has stood since 2012. Larsen worked on it for a whole eleven years. How long do the Swiss think it will take?

Mayeul smiles. "When we started the whole thing as a student project at the École Polytechnique Fédérale in Lausanne, we thought we would be there within three to four years." We were students back then. We're now in our seventh year, and almost everyone in the team has long since become an engineer."

Why a kite?

Record-breaking projects need staying power. And money. In this respect, the Swiss were lucky. Their main sponsor Richard Mille, a watch manufacturer, has been with them from the very beginning and remains loyal. Currently 40 other supporters ensure that the eleven-strong crew can keep its head above water financially.

And then the second question immediately pops into my head: why a kite? "The big advantage is that we can adapt to the wind conditions with the different kite sizes. And if the forces on the boat become too great, we can separate the kite from the boat in a fraction of a second at the touch of a button using a tiny explosive charge. This prevents damage or accidents," explains Mayeul.

It's certainly not a stupid idea when you consider that record holder Paul Larsen once took off in his first "Sailrocket" and completely flipped over in the air. He was only lucky not to be injured. When the three team founders Benoit, Mayeul and Xavier Lepercq were initially considering which of the three would have to give up the cockpit seat, Xavier was quickly chosen - he was the only one who already had a family.

SP 80 is more jet than tri

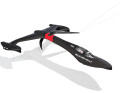

So much for the theory. But now it's off to the hangar, where the trimaran is being made ready for another test drive on its trailer behind a roller shutter. The sight is surprising: the boat looks more like a jet than a classic trimaran. The cockpit with a two-seater pilot's pulpit is embedded in a wide, teardrop-shaped centre hull. Its underwater hull is reminiscent of the belly of a seaplane.

The short, wing-shaped beams merge into two tiny fuselages. They look more like attached thrusters or buoyancy bodies. A long black swivelling boom is enthroned on top of the boat. The kite is attached to it.

Co-pilot and kite controller Benoit Gaudiot joins us. He starts by showing me his workplace, the rear cockpit. The steering wheel of a lawnmower tractor is actually mounted there, as the logo reveals. Benoit grins: "It fits perfectly and is very stable! I can use it to move the kite left and right. The angle of attack and altitude are adjusted with a lever next to it." It's all hydraulic. In on-board videos on YouTube, you can see Benoit turning the steering wheel quickly and a lot during the ride. It takes 14 turns from left to right.

A large red button on the right is the emergency release for the kite. In the centre is a large screen. "I can see where and how the kite is in the air."

Shortly afterwards, Mayeul slips into the narrow steering cockpit at the front. His job is to keep the boat at an optimum angle to the wind, around 100 to 140 degrees, and close to land so that the tri is slowed down as little as possible by waves. The boat data is collated on the screen in front of him: Load displays for the foil, rudder and kite arm, angle of attack, acceleration and much more. If the forces become too great, he can also blow off the kite.

Hyperventilating foil is new territory

From a speed of 25 knots, the hulls just skim over the surface of the water. The central foil keeps the boat in the water, supported by the tiny rudder blade operated by the pilot at the front. The rudder and foil are top secret, covered by covers; no one outside the team is allowed to see them. A diver only removes the covers in the water. No wonder, since the actual record-breaking expertise lies in these parts.

"We sail with a so-called hyperventilating foil," explains Benoit. The cavitation that sets in at just over 50 knots on a classic foil creates so many vortices and negative pressure that the profile is ultimately destroyed. This can be avoided with a foil that is almost triangular in longitudinal section. It draws in air from the surface, known as ventilation, which specifically places a thin layer of air over the underpressurised side of the profile. This prevents cavitation. The profile of the SP-80-Tris is said to be optimised for 80 knots, while Larsen's was designed for around 60 knots.

The foil is directly connected to the boom arm on which the kite is mounted at the top. If the kite produces too much upward pull, the foil is automatically adjusted in the water so that it pulls the boat downwards. This prevents the entire projectile from being lifted into the air. In terms of boatbuilding, this is all new territory, just like the hull. Mayeul reports that a lot of time went into the development.

They also had to put up with a few setbacks. "At the beginning of 2024, when we actually wanted to make the first fast runs, we discovered a tiny crack on the boat. It turned out that it was affecting the entire surrounding structure." The SP 80 had to be dismantled and a load-bearing part returned to the shipyard in Italy. The extensive repairs took over six months. It also turned out that the bow tip generated 90 kilograms of downforce before the boat started to plane. The boat was literally sucking itself in. "So we increased the underwater surface area."

Cockpits according to Formula 1 safety standards

New tests then began in June. With success. In just a handful of runs, the speed jumped from 13 to just over 43 knots. "That was our proof of concept!" says Benoit. However, in the end they had to jettison the kite by emergency separation. "The foil is designed for speeds between 40 and 50 knots. It got too much load, the tip bent over 30 centimetres to leeward," says Mayeul. Due to the high construction costs for the foils, they preferred to build several cheaper ones in order to have a choice. The decision was finally made in December and the final foil for the record was built and installed. There is now great excitement to see how the boat will perform with it.

Time for a real speed run! Outside, the wind is rattling the hangar at 30 knots, perfect conditions for a test with the 25-square-metre kite. The boat rolls out of the hangar to the slip ramp and is lowered into the water. Then it's a bit like "Top Gun": The two special glass canopies are closed over the pilots' heads from the outside by a crew member. The pilots sit one behind the other in their cockpits, which are tight as sardines. They are built to Formula 1 safety standards and can withstand forces of up to 50 G in the event of an impact. The pilots wear helmets with dark sun visors over them. Thumbs up, the radio communication is checked. Only now it's not the jets but the 300 hp outboard engines on the team rib that are humming away.

Showtime. The rib carefully manoeuvres the trimaran out to sea off Leucate in the south of France. Under a blue sky, it is gusty and icy cold at the beginning of December. 50-knot weather, the team hopes. As soon as they leave the harbour entrance, the rib driver, the SP 80 in tow, puts the lever on the table: they set off at 20 knots, around ten miles close to shore along the coast to the section that is ideal for the record attempt. The wind blows fiercely over a flat headland that weakens the waves. The Swiss radio to the coastguard to inform them of the record attempt and the number of people on board. You never know.

You can imagine what is possible with the SP 80

Once at the launch site, an anchor is dropped and the boat is moored to a mooring line at 90 degrees to the wind. Then a struggle with the kite begins. In the gusty wind, the large profile is spread out upside down so that it does not rise immediately. Countless thin lines are sorted and the sail is set on the rib's mast.

At the same time, the trained rescue diver switches to the SP 80 and attaches the kite's control lines to the boom arm. There are repeated delays. Meanwhile, everyone is connected via headsets. They are constantly discussing the situation, wind and problems.

After an hour and a half, the time has come: the rib crew releases the kite, which is now dangling from the carbon fibre mast. Trimmer Benoit first lets it rise and fly with little pressure. Then Mayeul pushes a button to release the boat from the mast. The SP 80, which weighs one tonne, slowly starts to move. Despite being less than 500 or 600 metres from land, the wave of perhaps 10 to 20 centimetres is giving it a hard time. And now, of all times, the gusty wind drops. Ribs are travelling in parallel as safety boats and the rescue diver is ready to go. Both pilots have undergone safety training in a mock-up of the cockpit in the overhead swimming pool in order to free themselves, but once again: better safe than sorry. There are even breathing masks and oxygen cylinders in the cockpit in case of an emergency.

The boat ploughs along at 15, maybe 20 knots. Then the course is corrected to the ideal wind angle. Benoit now steers the kite lower over the water and adjusts its profile. The boat accelerates immediately, but you realise that it is still "stuck" in the water during the planing phase. Then a strong gust comes in. The SP 80 sprints off in a flash. The rib driver has to accelerate hard to keep up. The record-breaking boat now flies stably over the waves. You can guess what is possible.

But then the wind drops and the hull sinks back. This goes on for a few minutes, then the end of the record distance, which is only a few miles long, is reached. Benoit lets the kite sink to the surface of the water, the run is over. The boat has too little power, they need the bigger kite. So they recover the kite, tow the tri to the anchorage, rig the larger kite - and start all over again. A soaking wet process for the rib crews in freezing spray.

Record hunters must be patient

Unfortunately, the planned second run is cancelled because the kite lines get tangled and the crew can't untangle them on the water. The risk of damaging the kite under load is too great. Record hunters have to be patient. After a long day on the water, the crew heads back to the harbour, somewhat frustrated.

Debriefing, then everyone wants to get to the warm team centre in the hinterland quickly. There the untangling of the lines begins. Kite specialist Tanguy Desjardins corrects the so-called bridle lines, which are used to control the angle of attack of the profile. They were not yet ideal.

Mayeul drops by again. The picture of Larsen's record ride with the autograph hangs on the wall. I want to know when he thinks he will beat his record. "Soon we'll be doing our first real record runs, now it's just a test. I think we can do it by the middle of the year; the boat can do it," he says confidently.

And then, in passing, he tells them that another record hunter has already knocked on their door: Glenn Ashby from Team New Zealand. He broke the speed record with a sail-powered vehicle on land in 2023. The Australian is now dreaming of a double: the record on land and on water. "It would be nice if he could do more than 80 knots," says Mayeul, "because we've set the pace!"