"All clear to dive": In a calm voice, Carsten Standfuß gives the decisive command for the "Euronaut" to leave the surface of the Baltic Sea off Rostock and dive into what I consider to be unearthly depths. Admittedly, I'm not really comfortable with the idea of gliding through the water in a few minutes in almost complete darkness.

But the actual process of descending is much less spectacular than expected. Standfuß slowly opens the valves to let the air out of the tanks. The air escapes with a slight hiss, and the only way to recognise that the "Euronaut" has left the surface of the water is by looking at the instruments.

The commander and the three crew members watch the displays with full concentration so that they can react quickly to any irregularities. Nevertheless, he has time to tell me something about the ship and how it was built.

"We spent twelve years building the 'Euronaut' and sacrificed every spare minute in summer and winter for the ship." He doesn't want to talk about money. Just this much: it will probably be two well-equipped detached houses.

And this despite the fact that, for cost reasons, he bought many parts that were never intended for a submarine. The seats in the command centre, for example, come from an Audi TT. The instrument that displays the oxygen saturation of the interior comes from a hospital, and the device for measuring the underwater inclination is a gyroscope from an aeroplane. He bought many of these components at auction on eBay.

But don't be fooled. The "Euronaut" is a professionally built underwater vehicle with impressive data.

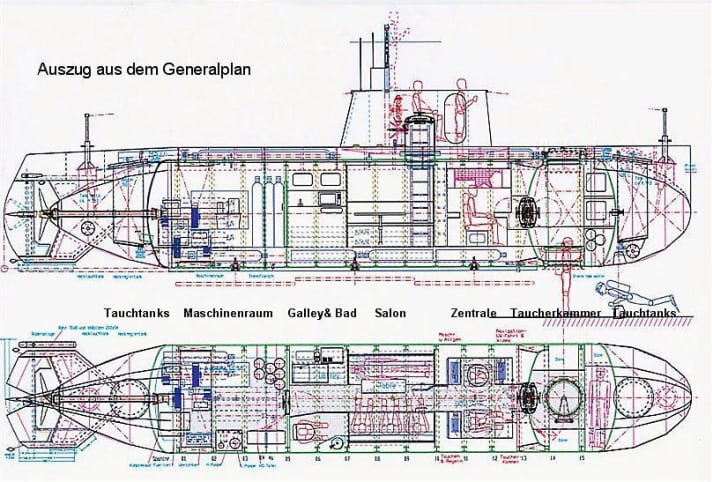

The nominal diving depth is 250 metres. With a length of 16 metres and a diameter of the pressure hull of 2.50 metres, the boat weighs more than 67 tonnes. The 22 millimetre thick steel hull is primarily responsible for this.

Inside, there is space in the centre for a small saloon with two benches so that the crew can rest during longer dives. At the rear is the engine room, where the 190 hp diesel-electric drive is at work. Towards the bow is the command centre with two workstations to the right and left of the passageway; a pressure lock is mounted in front of it, through which you enter the pressure chamber. This is large enough to comfortably accommodate two divers.

The "Euronaut" was actually built with this space in mind. Both Carsten Standfuß and his crew are enthusiastic divers. They are all united by a thirst for adventure and a love of wreck diving. There are probably still thousands of undiscovered wrecks in the North Sea and Baltic Sea that the crew of the "Euronaut" want to track down.

However, the physical and medical conditions often get in the way. For one thing, the water in the North Sea and Baltic Sea is so cold for many months that dives can only last a short time. Above all, however, the decompression time severely restricts the divers' room for manoeuvre.

The longer a person spends underwater and the deeper they are submerged, the longer it takes for their body to re-acclimatise to the lower pressure above water. This means that often only a fraction of the actual diving time remains for the actual work under water.

The pressurised chamber of the "Euronaut" is the solution. The pressure in the chamber can be adjusted to the pressure of the surrounding water. When a large hatch in the floor is opened, no water enters the boat - even at a depth of 250 metres. The divers can therefore get in and out comfortably and utilise the full diving time of their tanks. They can then complete the decompression time later in peace and quiet and in the warmth of the "Euronaut".

Carsten Standfuß makes sure that everything works. He is a naval architect and the "Euronaut" is not his first submarine. Before that, the self-confessed Beatles fan had already built the "Sgt Pepper", the smallest submarine in the world at the time. The experience gained from this project has been channelled into the "Euronaut", except that everything is a little bigger and more powerful. There is even a microwave, a sink and a toilet on board. But it has to be, because the maximum diving time is seven days.

And why a submarine? "In my youth, I was enthusiastic about space travel," says the 51-year-old. "But I ended up becoming a naval architect after completing my A-levels in mechanical engineering and then studying shipbuilding." But the longing for the unknown never left him, and so he combined his career and his thirst for research by building submarines.

All he needs to steer the boat, by the way, is a sports boat licence, just like for any other boat with more than 15 hp. Standfuß has also done a lot for safety. For example, all of the hull's weld seams have been x-rayed and, in an absolute emergency, three massive steel plates, each weighing one tonne, have been fitted under the boat, which can be released and dropped from the inside so that the "Euronaut" can come to the surface on its own.

Over the years, a group of around a dozen enthusiastic submarine fans and hobby divers have gathered around him, who take it in turns to form the four to five-man crew. At weekends, they are usually out on the Baltic Sea off Rostock, investigating submarine wrecks from the Second World War or sunken merchant ships.

Carsten Standfuß would like to see even more interest in his self-built submarine. Divers from the Rostock area in particular would be very welcome as future crew members, but he is also thinking of archaeological institutes or private companies. "We don't want to earn money with it, but rather make our knowledge, experience and skills available for underwater research." The main thing is that he can continue to get to the bottom of the sea with the "Euronaut".