The skipper is responsible for the safety of the boat and crew, regardless of whether it is an inflatable boat, a day cruiser or a large motor yacht and regardless of where it is going.

Some trips last only minutes, others months. Or the experience of the individual people on board: Who is familiar with seamanship and what roles can be allocated? How can the others help? It is the skipper's job to take all these factors into account in his considerations and decisions - and not just after casting off, but already when planning and preparing the voyage.

In addition to these "variables", which will be dealt with a little later, there are a number of other aspects with regard to thorough preparation andMaximum security However, there is also a "set size": the equipment and fittings. It must be reliable in every situation and without compromise. In addition to being in perfect technical condition, this also means that versatility and performance must be right.

Of course, you don't necessarily need a radar if you're only travelling inland. And there is rarely room for a life raft on a fishing boat. Nevertheless, there are things thatCompulsory and are the subject of the next section. If the safety equipment is more comprehensive, all the better! Because a really good feeling of safety also means that you can relax better and have even more fun on the water.

The personal equipment

By far the most important part of every crew member's safety equipment is theLifejacket. The situations in which it can prove its worth when a person falls overboard are endless - one wrong step, one unexpected wave is enough to lose your balance. In the harbour, in the lock chamber or on the high seas, on the jetty, at anchor or at full speed.

Anyone who falls uncontrollably into the water from a certain height can not only lose their bearings, but sometimes even lose consciousness - a life-threatening situation. Faint-proof automatic waistcoats, which activate and inflate automatically, provide protection even in this case by turning the person through the arrangement of their buoyancy chambers so that at least the head is above water.

In addition to the lifejacket, there are a number of other points that are important for the health of the crew: Clothing must be appropriate for the area and the weather and be able to fulfil the relevant protective functions, for example in strong sunlight, wet or cold conditions. Sturdy footwear - especially when working on deck - is also important.

If you have to move quickly, a sudden unfortunate injury to a bare foot caused by edges or fittings can quickly disrupt the entire manoeuvre. Equally important are sunglasses (which also act as wind protection for tear-free vision at high speeds) and suitable headgear.

You should also apply sunscreen (even in light cloud cover, the surface of the water still acts like a mirror) and possibly a product to combat dry skin. In any caseSufficient drinking water on board be. Take special care to ensure that children are properly equipped at all times.

The boat equipment

The EU Directive 2003/44/EC sets out basic safety requirements for the design of recreational craft. In contrast, there are no regulations for safety equipment in Germany, only recommendations based on the four directive categories A (formerly "high seas") to D (formerly "protected waters") and the corresponding areas of use.

The following are proposed: For categories A, B, C and D: Approved position lighting, the flags "N" and "C" as simple visual distress signals, as well as a red flag inside (mandatory), shut-off valves for fuel tanks, anchor (which must always be easily accessible and ready for use), tools, outboard ladder, first aid kit, ABC powder extinguisher and fire blanket, smoke detector, hand lamp, fog horn, hand bilge pump, bailer, towline, boat hook, throwing line, binoculars, depth sounder, life jackets, life belt, smoke signal (orange).

Additionally only for categories A, B and C: sea railing, spare anchor, leak sealing material, radar reflector, bilge pump, magnetic and bearing compass, log, GPS, navigation equipment, chart plotter with current software, classic paper charts and nautical manuals for the area, safety harnesses, parachute rockets, hand flares.

Additionally only for categories A and B: drift anchor, sound signalling system, bell, VHF radiotelephone system with GMDSS and a sufficiently dimensioned life raft.

Finally, for category A only: a sextant for navigation and a distress beacon (EPIRB).

However, many of the items of equipment that are only suggested for the "higher" categories have long been found on other boats.

This applies, for example, to electronic navigation devices and VHF radio.However, even this list of suggestions does not mention some items of equipment- perhaps also because their presence not only corresponds to good seamanship, but also to thecommon sense.

This includes lines of sufficient length, quantity and good condition, as mooring lines or for other purposes, as well as fenders of the right size. If you do not have adequate railings, you should at least make sure that the deck surface is non-slip and that there are easily accessible, solid handrails or handles.

Especially for manoeuvres, theThe foredeck of both small and larger boats must be safely accessible at all timesThe width and condition of the side deck are the decisive criteria here. Also helpful: a dinghy that is at least equipped with oars. It's not just full-grown dinghies in their own davits that count - even a small inflatable boat can make all the difference. And a model with an inflatable floor can also be set up quickly and easily on board.

Incidentally, outboards are not only an issue in connection with dinghies; as auxiliary engines, they can also keep larger cabin cruisers manoeuvrable if the main drive fails. Yachts designed for long journeys in particular, such as trawlers, are often even equipped with an additional permanently installed engine as a get-home system for this case.

Speaking of outboards: the quickstop line is also part of the safety equipment. Attached to an arm or leg, it should be mandatory even on short trips, regardless of whether the boat only has tiller steering or a proper steering position with fixed seats, and regardless of whether you are travelling alone or with several people.

The right combination

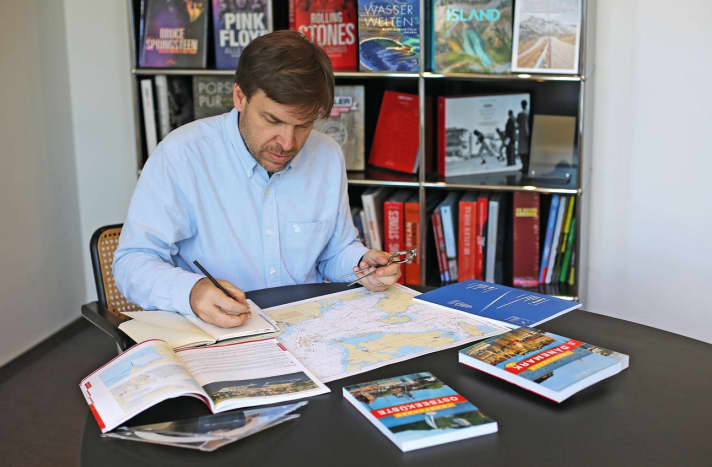

In addition to the equipment, theComprehensive preparation of each trip (and in the further course of the trip, every single day) is the most important prerequisite for a relaxed and safe journey. If a sailing area is being travelled to for the first time, all the more time should be invested in the preparation beforehand.Reading the relevant nautical literatureand map material.

It not only provides information about theGeneral nature of an areaThe information is not just about the tides, currents and weather conditions, but also about later important details and parameters, such as approaches, water depths and mooring possibilities in general, from anchorages to clubs and commercial marinas to city harbours.

They also provide information aboutLegal issues for example with regard to clearance or registration formalities, in particular traffic or environmental regulations or the responsibility and alerting of authorities and rescue services. Only once you have familiarised yourself with an area in detail can you assess whether it should be considered as a destination.

The suitability of the boat

Are the seaworthiness, equipment and range of your own boat appropriate for the conditions and distances of the area in question? What about the clearance heights, especially with fixed bridges, and the water depth - especially if it is a tidal area or a watercourse with variable water levels?

Are there petrol stations directly on the water or bunker boats? And if so, must it also be ensured that the right type of fuel is offered there? As an alternative, would there at least be road petrol stations within reach? It is also important to clarify which harbours and berths are suitable for your boat.

Here, too, theDimensions such as draught and width plays a decisive role. Only realising at the harbour entrance that you don't fit into the boxes or not even getting that far because it gets too shallow beforehand leads to annoying stressful situations that can easily be avoided with thorough preparation.

Another point in this context isAdditional equipment specific to the areaWould a lock hook, an extra spare canister, additional longer lines or a fender board be helpful? Most cruising guides also provide helpful tips on what is particularly important in this respect.

Nature of the territory

How demanding is the cruising area beyond that? Various factors can be important here both inland and offshore, for example the general nature of the coast or the course of the shore, the depth profile and the distances between harbours or other suitable moorings, the characteristics of the tides or the strength of the current conditions, water levels and water levels.

Are there fixed fairways (possibly evenwith its own traffic rules) and how good is the labelling with navigation signs (by day and night)? Are there any differences to known areas? Is commercial shipping to be expected and what is the general traffic volume like?

The suitability of the crew

The skipper himself has full responsibility in this respect: is his own experience and seamanship sufficient for the expected cruising and area conditions - and does this still apply when heading for a new destination with largely unfamiliar personal situations, such as tides or large shipping locks?

In this case, thorough preparation is particularly important. The same naturally applies to each individual crew member and to the crew as a whole. Are the group dynamics right? Difficult circumstances inevitably lead to particular stresses when working together.

Weather and weather conditions

WhichWind and weather conditions Are the prevailing weather conditions at the time of travelling, should extreme exceptions be expected? Can special weather phenomena occur, for example local weather conditions, strong and stormy winds that set in quickly and unexpectedly or frequent fog?

Land-side infrastructure

Are there enough berths (and alternative options? It may be necessary to register in advance. What are the other service and supply options (operating hours)? Where can you slip and crane? What language is spoken?

Route planning

Of course, the route planning itself primarily depends on how much time you have available. If you really want to go on holiday, "eating up kilometres" should not be the goal. If you arrive too late (especially in the high season), the moorings may already be taken and the shops closed (not to mention the sights).

Rest days and reserve days are important for safety: on the one hand, breaks are needed on longer trips. On the other hand, the weather can quickly disrupt a well-organised stage plan. If you have to sail every day to cover the required distance, you are putting yourself under unnecessary pressure - at the expense of safety.

Even a series of very long days on the water can be exhausting, regardless of whether you are travelling inland or offshore. The wind, direct sunlight and swell also drain your reserves - especially if a crew member does not regularly travel by boat.

Six to seven hours per day should therefore not be exceeded when planning, even in this case including the reserve, of course.

Christian Tiedt

Editor Travel

Christian Tiedt was born in Hamburg in 1975, but grew up in the northern suburbs of the city - except for numerous visits to the harbor, North Sea and Baltic Sea, but without direct access to water sports for a long time. His first adventures then took place on dry land: With the classics from Chichester, Slocum and Co. After completing his vocational training, his studies finally gave him the opportunity (in terms of time) to get active on the water - and to obtain the relevant licenses. First with cruising and then, when he joined BOOTE in 2004, with motorboats of all kinds. In the meantime, Christian has been able to get to know almost all of Europe (and some more distant destinations) on his own keel and prefers to share his adventures and experiences as head of the travel department for YACHT and BOOTE in cruise reports.