Who likes to buy a pig in a poke? Owners of life rafts - you might think. Because even those who try to get comprehensive information from dealers and at boat shows usually don't know how the raft will behave in an emergency and whether the equipment hidden inside is really usable. Neither the buoyancy stability of an island nor the access can be conclusively assessed on dry land. And the accessory pack is usually not even visible at trade fairs; it can only be inspected after purchase in the course of maintenance.

This means that scepticism is the order of the day when buying a life raft. There are hardly any reliable rules for use on pleasure craft, and in an emergency the lives of the crew can depend on whether the product is really good or just cheap.

Although the ISO 9650 standard introduced in 2005 specifies standards for materials, construction, size, buoyancy and equipment, it is unfortunately not binding. This means that different requirements apply to life rafts in different countries - or none at all.

Nevertheless, the standard is a good guide. It divides the models into two groups. On the one hand, there are those for coastal voyages (ISO 9650-2) and on the other, the offshore versions, which must comply with the ISO 9650-1 standard. These islands are divided into classes A and B depending on the operating temperature.

For the test, we limited ourselves to islands available in this country that comply with ISO 9650-1, Class A - or as the standard jargon has it: they should be suitable for long voyages in rough seas, release safely down to minus 15 degrees and are equipped with an insulated floor that minimises heat loss.

This extra seems unnecessary from the standard text - who is travelling with their boat in temperatures below freezing? However, practical experience shows that a simple rubber floor quickly becomes very cold, even at a pleasant water temperature of 22 degrees. Finally, it must be assumed that the crew will be severely weakened when they board the island because they will have been fighting for their own boat for several hours and will be physically and mentally exhausted.

What the island should be able to do

The most important test criteria also follow from this scenario. The island must be easy to transport overboard and activate. The steps required for this should be shown on the bag as easy-to-understand pictograms. Depending on where it is stowed, the weight of the island also plays a decisive role.

Ideally, the weight distribution in the bag ensures that the island floats upright and ready to board next to the boat after inflation, so that the crew can board it dry. Depending on the swell and wind conditions, this scenario will not always be the case and the island may capsize when inflated. If this happens, it must be easy to right again and must not tip over again when climbing on board in rough seas.

When boarding the island from the water, the easier it is, the better. This is because exhaustion and hypothermia quickly sap the strength of even well-trained crew members. Once on the island, it is important to help other crew members to board. Stability must not be jeopardised here either. Furthermore, the knife for cutting the safety line must be easy to find, but must not be able to damage the rescue refuge.

In addition, the interior and exterior lighting of the island should be activated, a floating anchor should be ready and the remaining equipment, such as torches and distress signals, should be secured in a waterproof bag near the entrance.

It goes without saying that the roof must be closed to protect against spray, rain and sunlight on an offshore island. However, in order to be able to ventilate and keep a lookout, there should be closable openings on various sides.

Where the islands come from

The six test specimens are each designed for four people and come from Arimar, AWN, Crewsaver, Plastimo, Seago and Sostechnic, whereby the latter is manufactured by the English manufacturer Ocean Safety. We have chosen the lighter bag version for the packaging; all candidates are also available in a container. In both designs, the island is in vacuum packaging, so it is unlikely that the test results will differ. Only the price and weight may differ.

These points already vary greatly within the test field. The AWN ISO model from A. W. Niemeyer is the cheapest. It costs just over 1000 euros and is the only self-righting island in the test. The Ocean ISO from Sostechnic costs almost twice as much, namely 1990 euros.

At less than 28 kilograms, it is on a par with the Transocean 4 from Plastimo, but unlike the French model, it has two litres of drinking water on board in addition to the ISO-compliant basic equipment.

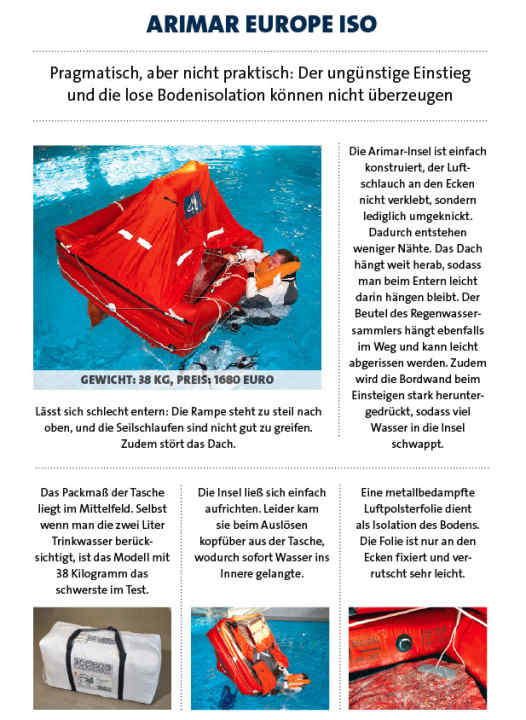

This additional liquid ration can also be found on the Arimar. However, the Italian island also weighs ten kilograms more, making it the heaviest test candidate. Hoisting the 38-kilo package overboard in an emergency is a real task.

How we tested

The islands were tested at the Maritime Competence Centre's offshore training centre in Elsfleth on the Weser. Not only can different sea states be simulated in the centre, but also rain and wind up to gale force.

After releasing the packages in smooth water, we climbed onto the island from a simulated bathing ladder, assessed the interior and carried out an inventory. Depending on whether a rescue from the island is expected within 24 hours or not, ISO 9560-1 requires different basic equipment. Thanks to their integrated drinking water ration, the models from Arimar and Sostechnic can be easily upgraded for longer stay times using an external grab bag. The basic equipment must be extended for the other islands.

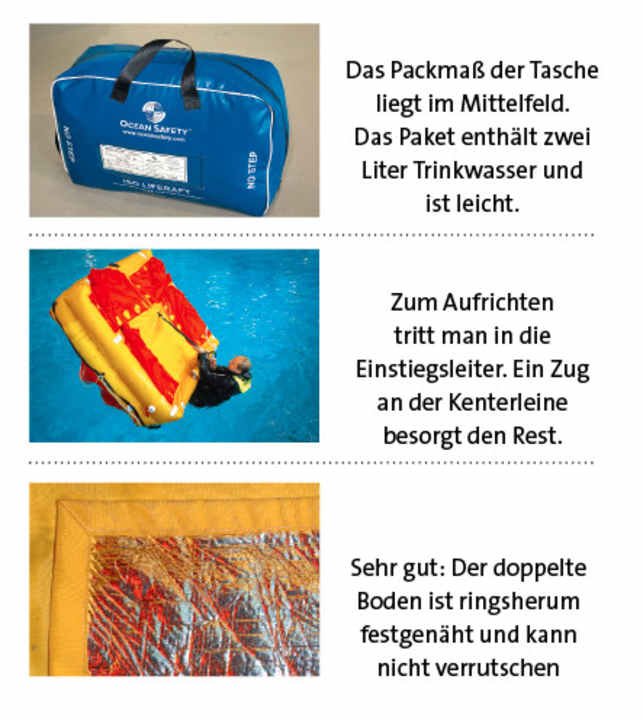

The islands were then capsized and righted one after the other by different people. This took place automatically with the self-righting product from AWN and was also successful with all other models - in contrast to the subsequent boarding of the islands from the water. In full oilskins and with an inflated lifejacket, this is no easy exercise, although the waistcoat is definitely an advantage: in order to get the foot into the first step of the boarding ladder, a strong supine position is sometimes required - without the buoyancy of the waistcoat, the head is quickly washed over even in smooth water.

This problem occurred mainly on Crewsaver Island. The rope ladder is not weighted and floats on the surface, making it very difficult to thread your foot in. Once the first step has been taken and both feet are in the ladder, the access ramp can be climbed.

Where available, this is made of a spread fabric panel on the test models and is intended to serve as a reasonably stable platform to support yourself with your knees and master the next challenge: the upper body has to get over the side of the boat. For this purpose, the islands have more or less favourably positioned straps or rope loops on the inside.

Here too: The disadvantage of Crewsaver - the straps, which are actually easy to grip, end too early. Instead of sliding over the tube on your stomach, you are tempted to sit upright on the ramp. However, the capsize bags are not able to cope with this shift in centre of gravity and the island overtakes strongly. If you still manage to stay on it, the steep incline causes the capsize bags to partially deflate and the island can flip over.

Plastimo and Sostechnic prove that there is another way. Their products are not only very stable in the water, but are also much easier to board.

When the waves come

Hardly any island will be deployed in completely calm seas, so we repeated the launch attempts with the swell generator activated. The first attempts at maximum power were sobering, even frightening.

A wave height of just under 1.5 metres doesn't sound particularly bad. However, the fact that an extreme cross-sea built up in the basin meant that we were washed over so often when boarding the islands that even the good boarding systems from Sostechnic and Plastimo became a challenge.

This changed surprisingly little at low wave heights. At the weakest level, the simulator generated a uniform swell of around 40 centimetres. Although all islands could be boarded under these conditions, the differences were clearly noticeable. Conclusion: The best boarding system is just good enough.

Conclusion

This also determines the test winner: the Ocean ISO island from Sostechnic made the best impression. The cheaper Plastimo Transocean 4 also did well, but the entry systems of the other islands were not convincing. Seago is working on the problem, and Crewsaver could also perform much better with a weighted rope ladder and an additional grip strap.