Copper - everyone knows the colour, but on board cables made of this material often have a different surface: black. The skipper usually discovers cables of this colour when searching for loose contacts. This is by no means a coincidence. This layer is copper oxide, comparable to what is commonly known as rust on steel - not particularly favourable for electrical contact.

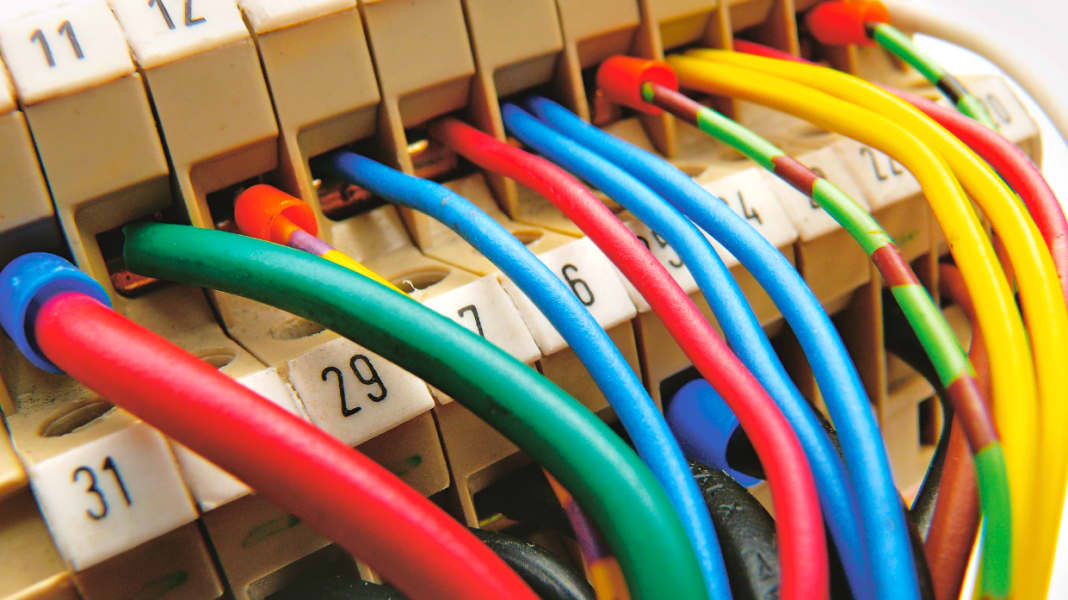

It's not just the colour that causes headaches. The visible part of the copper is usually stuck in some kind of terminal, and there are versions of these that develop an undesirable life of their own. The result ranges from unstable contacts to partial failure of the vehicle electrical system.

Surface observation

Why does the cable turn black? Oxide is always a combination of the base material with oxygen. In contrast to the porous, constantly progressing rust on steel, copper forms a dense oxide layer that protects the remaining material underneath from further reactions. In a protected environment, this layer remains very thin; cables in domestic installations, for example, still look fresh even after years.

Not so on board. Humidity and salt content cause much stronger oxidation. This layer is also sealed at some point if the cable is thick enough, so that the process stops by itself. Many cables that have turned black on the outside continue to perform their service for years. But the layer is more brittle and less flexible than the copper underneath. With thick, single-wire conductors, as is common in fixed land installations, this does not matter.

However, such rigid conductors are not suitable for connecting cables of moving devices or in the entire on-board installation. They would break quickly due to the constant movements and vibrations. Stranded wire must therefore be used in vehicles and machines. This consists of many fine copper wires that are processed into a stronger conductor. In this way, the cable remains flexible even with large cross-sections. The rule is: the more individual wires, the better the stranded wire.

However, the oxide layer on a stranded copper wire cannot keep up with the movements it allows and cracks appear. These in turn allow air or moisture to reach the bare copper, which oxidises again until the layer is once more impermeable. That actually sounds good, the automatically formed protective layer is even self-healing. Unfortunately, however, with each new healing process, a little of the copper conductor is used for oxide formation.

Example: The wiring harness from the machine to the control panel hangs on one side on the soft-mounted engine block, on the other it is firmly screwed to the next bulkhead. These cables are therefore constantly in motion when the machine is running.

There are many similar places in the ship where cables are exposed to permanent unrest. If, as a result of damaged insulation or contact with water, new oxygen is constantly available for oxidation, the copper eats itself up over the years. Black crumbs remain of the former conductor. It is rare for this to happen, as the function suffers much earlier.

Matter of resistance

While copper itself is a very good electrical conductor, the oxide is more of an obstacle to electricity. It is one of the semiconductor materials. Due to a growing oxide layer, the effective cross-section of the cable is reduced. The finer the individual wires of the strand, the faster this happens. Result: The electrical resistance increases.

The effect of this oxide layer is really nasty in high-frequency cables. In these, the outer conductor consists of copper braiding. Due to the contact between the individual cores, it acts electrically like a continuous tube. This contact no longer exists in the black state. Instead, you suddenly have many individual wires, each of which is wrapped around the core in a helical shape. As a result, the distance that the current has to travel is now much longer. The high-frequency properties of the cable no longer have much to do with the original specification.

With a VHF marine radio system, this often manifests itself as follows: While reception still works reasonably well, the transmission range is only minimal. The cable absorbs the transmission power at the bottom of the ship, but virtually none of it reaches the antenna at the top. Due to the increased resistance, it is converted into heat and fizzles out ineffectively. The worst thing about this is that such a fault can hardly be detected with the usual measurements used to test the radio installation.

YOU CAN FIND THE COMPLETE GUIDE IN THE CURRENT DECEMBER ISSUE FROM BOOTE