An unforgettable moment in film history: pursued by the Coast Guard, the classic motor yacht "Disco Volante" of James Bond villain Largo blows off its cocoon and takes off at high speed. The bow rises - and to the amazement of the audience, a V-shaped hydrofoil appears in the bow wave.

Shortly afterwards, the whole ship begins to fly. "A hydrofoil", the film world marvelled at the time. A concept that had been researched for many decades, but never really made the breakthrough.

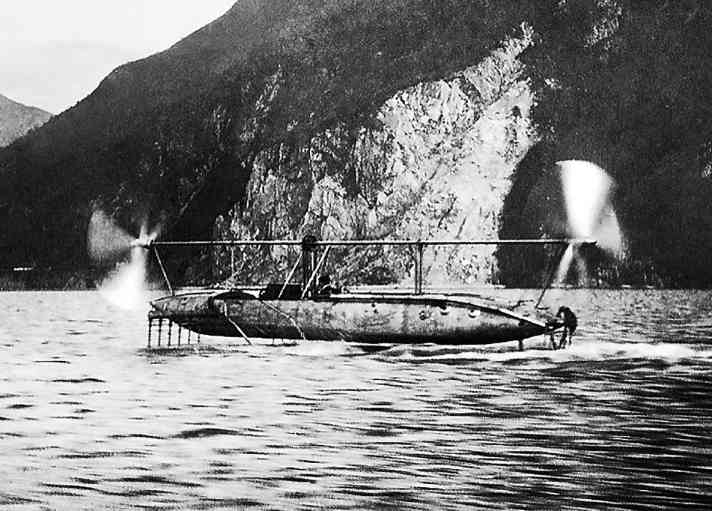

However, hydrofoils or modern "foilers" are not only known in Hollywood. Ever since the Italian airship builder Enrico Forlanini left the surface of the water with a propeller-driven boat on Lake Maggiore in 1906 and floated across the water at 38 knots, designers have been trying their hand at the principle, which is as simple as it is logical.

"Achieving higher speeds has always been very desirable in all forms of transport",

writes A. J. Acosta in his work on hydrofoils (California Institute of Technology, 1973) and describes that there are limits to this possibility on the water.

"The water surface is inherently a rather inhospitable environment for achieving high speeds."

On the one hand due to the rugged surface, because even small waves can make fast travelling quite unpleasant. In addition, the frictional resistance of the displacing boat and even that of the gliding yacht costs a lot of fuel and slows you down enormously. This is why it has always been a logical step for Acosta and many other inventors to mount hydrofoils and lift the boats into the air.

The physical background of an airfoil with a flow around it is similar in hydrodynamics and aerodynamics: the water flows around the airfoil, and the longer path on the upper side creates an upward force that pulls the airfoil upwards and thus lifts the boat out of the water.

The greater the speed, the greater the power.

Hydrofoils are able to move in two modes: During harbour manoeuvres in displacement mode, where the hydrofoils and their holders are completely under water. If the boat then accelerates, it lifts itself out of the water until it floats completely on its wings and is in "flying mode".

The travelling speed is then often double the withdrawal speed.

The British engineer Thomas William Moy is said to have carried out such experiments in the Surrey Canal in England in 1861 by mounting two rigid wings under a wooden barge and having it pulled by a team of horses on the bank. 45 years after Moy's towing experiments, Forlanini finally got the first self-propelled foiler to fly.

He had spent eight years researching the concept and developed a boat that reached a speed of 68 km/h, powered by a 60 hp engine and a propeller. To keep the boat in a stable flight position, he built a total of four foils under the boat, which looked like ladders.

In his experiments, he had discovered that lift is dependent on increasing speed and therefore less wing area is required to generate the same lift at higher speeds. This is why he arranged his ladder wings on top of each other in a trapezoidal shape, wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, so that the same lift is generated at slow speeds as at high speeds.

The American inventor and engineer Alexander Graham Bellwho became famous for inventing the telephone, happened to read a scientific article about hydrofoils in March 1906 and immediately realised that he wanted to build the fastest foiler in the world. Years later, while travelling around the world, he met Forlanini and took him for a test drive on his boat.

However, it was only after the end of the First World War and the availability of large engines that he succeeded in setting a speed record of 114 km/h in 1919 with the HD-4, powered by two 350 hp engines.

Despite the same principle, the wings have to be dimensioned completely differently in water than in the air. One reason for this is that water is around 800 times denser than air at sea level. This is an advantage, as the high density means that the wings can be much smaller.

The other difference lies in the water surface, which limits the lift because the wing cannot break through it completely. Unlike in aircraft construction, wings must be present at the bow and stern so that the vehicle remains horizontal.

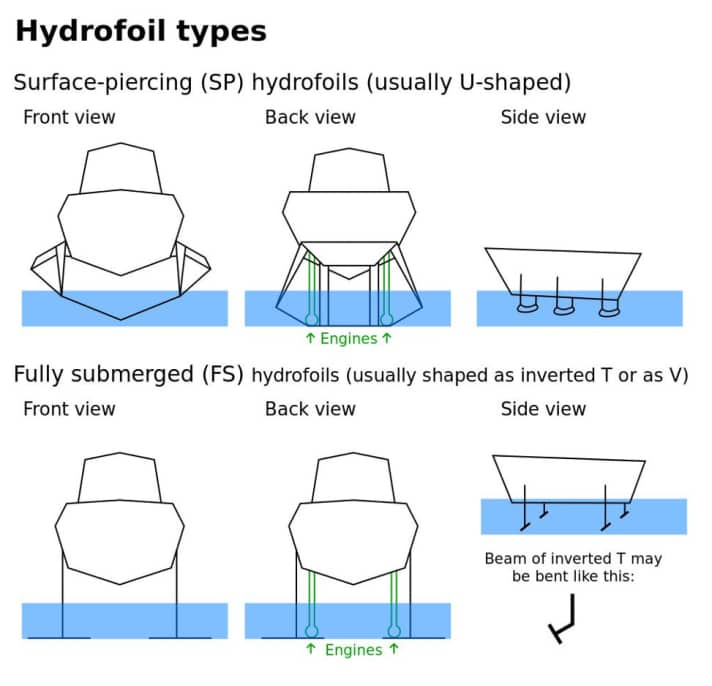

Forlanini had taken all these things into account in his calculations. Nevertheless, his ladder foils never caught on despite the well thought-out approach. Instead, two others did: the partially immersed and the fully immersed type.

Both have a profiled wing in the lower section. On the partially submerged type, this is bent in the centre, i.e. in a U or V shape, and mounted with sturdy struts transversely under the bow and stern of the ship. The retaining struts can also be seen above the waterline during displacement travel. When travelling at speed, the V-wing is pulled upwards and, at full speed, one third of the tips of the wing even emerge from the water.

At slower speeds, the boat sinks a little further into the water, so the buoyancy changes continuously.

The fully submerged type has a horizontal, often steerable wing, which is attached to a vertical T-shaped bracket under the hull in a fixed or folding position.

When travelling fast enough, the airfoil generates the necessary lift to lift the boat upwards. The control of the hydrofoil makes it possible to maintain a certain diving depth of the hydrofoil or flight altitude of the boat.

In Germany, Hanns von Schertel was a pioneer in the development of hydrofoils. With the aim of transporting passengers on the Rhine, he built seven experimental boats until he was successful with his "Silbervogel". The boat had a 50 hp engine, a V-foil at the front and a trapezoidal foil at the rear. With seven passengers, it reached a speed of 55 km/h in 1934. This impressed the press and convinced the Rhine shipping company to order a ferry - the world's first commercial order for a hydrofoil.

But the war thwarted further civilian research.

As it was initially no longer permitted to build boats with speeds of over 12 knots in Germany in the post-war years, von Schertel continued his research at Supramar AG in Switzerland. The PT-10 developed there was the first commercial production boat and was put into service in 1953 as a ferry on Lake Maggiore, the place where Forlanini had made the first flight 47 years earlier.

In the following years, Supramar launched the further developed PT-20 on the market. One of the ferries that left the slipway in Italy was the "Flying Fish", which later achieved brief fame in Hollywood as the "Disco Volante".

The greatest difficulty in developing hydrofoils was controlling the flight so that the boats did not stumble over a wave or even crash on landing.

The V-Foils (partially submerged) are much more stable in smooth water, as they rise and fall in a very controlled manner when the speed changes. They are more sensitive to waves, as the wings are designed for an even flow and are thrown off track by waves hitting them crosswise.

T-wing gliders are generally a little more wobbly when climbing in the flying position. However, once they are in the air, they behave much better in rough seas because they run on their submerged wing and the waves usually pass underneath them. It was not always easy to keep T-wing gliders in a level flight position.

Today, modern technology helps; in the beginning, it was still fragile mechanical controls that kept the boats levelled via trim tabs. This is why the commercial operators of river ferries favoured the simple but robust V-planes. Especially on the rivers in Russia and the Ukraine, where the boats are still very popular today.

The American Navy developed several foiling patrol boats in the 1960s in collaboration with aircraft manufacturers. The 35-metre-long "High Point" was built in 1962 by a Boeing subsidiary in Seattle and was able to carry out its patrols completely unobtrusively in displacement mode, powered by a conventional diesel engine.

However, it also had lowerable foils and two gas turbines, which allowed the 110-tonne ship to fly at 48 knots under the control of the first computer-controlled automatic stabilisation system.

After the great inventions at the beginning and middle of the last century, foilers, now controlled by modern gyros and flight computers, are in the hot phase of their return. Foiling motorboats are even being built in series and can hardly be compared with those of earlier times. Take the Candela 7 from Sweden, for example, which runs on electricity.

The rear T-foil is also the drive, while the front two-bladed V-foil is permanently under water but can be retracted for towing. With a full battery, the 1300-kilogram boat has a range of 50 nautical miles at around 20 knots. At peak speeds, it can even reach 30 knots. The ten metre long luxury

motorboat "Foiler" from Dubai can even reach 40 knots and flies 1.5 metres above the water.

Powered by two 370 hp diesel engines. The highlight: the front, laterally projecting L-foils can be folded up at the touch of a button. RIB manufacturer SEAir also has two models that fly on two L-foils and one T-foil (on the outboard motor). And then there is the new generation of foiling and electrically powered surfboards, which can now be seen as toys on mega yachts in the Caribbean at every anchorage. Controlled by remote control, they can reach speeds of up to 24 knots.

Foilers have always been complex to develop and expensive to manufacture because the stress on the material is naturally enormous.

That's why modern standard foilers are also expensive: the Flite surfboard is available from 13420 euros, the Candela Seven from 291000 euros and the Foiler even from 909000 euros.

Will the modern foilers spread this time - or are they just another fad?

In any case, the older generations have all disappeared: The jetfoil high-speed ferries (type 929) once built by Boeing and popular all over the world have all been sold to the Far East and are slowly being phased out there too. The "Disco Volante" enjoyed brief fame and eked out an existence as a houseboat in Miami until it sank neglected on the jetty.

The "High Point", once the pride of the Navy, now lies weathered, dilapidated and gutted in an industrial estate in Oregon and is for sale for 69,000 US dollars. There is no longer a market for boats like this.

Small, fuel-saving fun boats like these are in demand in this development phase of foilers. Will today's foilers have a similar fate in a few decades' time because they are so extreme? Or will they be considered a milestone in development?

In his book "High Performance Ships", published in 1960, the naval architect A. Silverleaf already considered whether there might not be a middle way between displacement and foiling for less performance-orientated utility boats:

"Then the weight of the ship would be borne partly by the displaced volume and partly by the buoyancy of the wing."

Although such a ship would not fly, it would still "move through the water with less draught and displacement".

In fact, some designers have now tried to realise such a hybrid concept, like Hysucat from North Carolina: an open motor catamaran with a rigid T-shaped wing attached between the hulls.

Although the boat remains fully submerged, the buoyancy generated reduces drag, should save fuel and increase speed by up to 15 per cent. A concept that does not fully utilise the potential of hydrofoils, but is more practice-oriented.