In 2025, the North Sea experienced the hottest summer since records began in 1969, averaging 15.7 degrees Celsius. Temperatures were two degrees above the long-term average across the board. The Baltic Sea also recorded significantly higher values, which had the expected consequences.

The North Sea reached record temperatures in the summer of 2025 "Our preliminary results show that the North Sea was on average around 15.7 degrees warm in summer. This makes 2025 the warmest summer on record for the North Sea, just ahead of the record summers of 2003 and 2014, if these figures are confirmed over the next few days. In any case, the summer of 2025 will be one of the three warmest since measurements began in 1969," explains Dr Tim Kruschke, Head of the Marine Climate Division at the BSH.

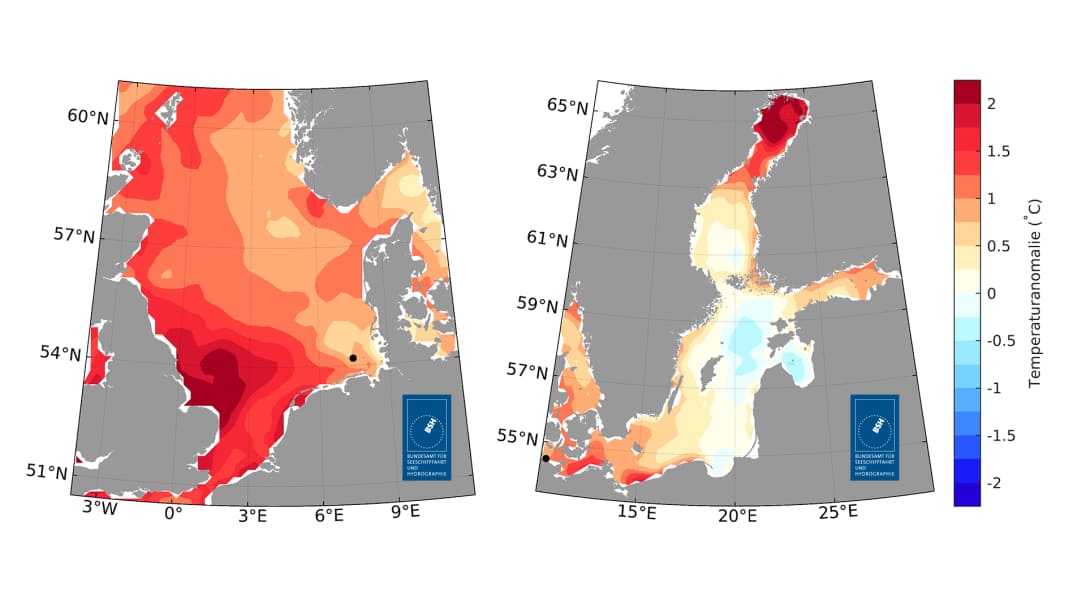

It is worth noting that extremely high temperatures of up to two degrees above the long-term average were measured over large areas in the western and south-western North Sea up to the English Channel. The German Bight and the eastern North Sea, including the regions off Denmark and Norway, were up to 1.3 degrees warmer than usual. The record summer followed the warmest spring on record. Researchers see this as a further sign of advancing climate change.

July with extreme water temperatures

In July, the entire North Sea warmed to temperatures more than one degree above the long-term average. Only the German Bight showed somewhat more moderate temperatures. Although large parts of the North Sea cooled down in August, temperatures remained high off the British coast and in the English Channel. These observations were confirmed by the annual survey of the entire North Sea with the research vessel "Atair", which was carried out from mid-July to mid-August.

Dr Dagmar Kieke, chief scientist and head of the Oceanographic Assessments department at the BSH, observed the temperature changes directly on board: "In July and August, the near-surface water layers of the North Sea were significantly warmer regionally than in 2024, with temperatures 2 to 3 degrees higher in some places. We see a connection with a pronounced marine heatwave off Norway this summer, which extended into the North Sea - a phenomenon that occurs more frequently in times of climate change."

Baltic Sea also significantly warmer

The Baltic Sea also recorded above-average temperatures. In the summer of 2025, the temperature in the south-western Baltic Sea, including German waters, rose by up to 1.5 degrees above the long-term average from 1997 to 2021. In the far north, it even exceeded this by more than two degrees. Temperatures were somewhat more moderate in the central areas, so that the preliminary analyses show an average temperature of around 16.7 degrees. Dr Kerstin Jochumsen, Head of the Oceanography Department at the BSH, emphasises: "The Baltic Sea is warming faster than the North Sea in the long term. Our data proves this. Since 1990, the Baltic Sea has become almost 2 degrees warmer on average."

Marine heatwaves on the rise

Rising average temperatures are just one aspect of the changes. Extreme events such as marine heatwaves are also increasingly occurring. In spring 2025, the BSH measuring station "Kiel Lighthouse" recorded the longest marine heatwave since measurements began in 1989, lasting 55 days. During marine heatwaves, the temperatures for at least five days are among the highest 10 per cent of the values measured over 30 years at the location in question for the respective season. The long-term data from the "Kiel Lighthouse" station show a clear trend: marine heatwaves are becoming both more frequent and longer. The number of heatwaves per year is increasing, as is the total number of heatwave days.

Why are the oceans getting warmer?

Greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane and nitrogen oxides in the atmosphere trap heat that would normally be radiated from the earth into space. An increased concentration of these gases leads to greater heat storage in the atmosphere. The oceans, in turn, are in constant thermal contact with the atmosphere: They not only give off heat, but also absorb heat from the atmosphere. Water has a high heat capacity and stores considerable amounts of heat energy, which leads to a general warming of the oceans.

The oceans also have natural mechanisms for heat radiation and exchange between different layers of water. However, if the surface temperature rises due to the greenhouse effect, these mechanisms may become less effective. A warmer water surface reduces the exchange of heat between the warmer upper and colder deeper water layers. The heat remains closer to the surface.

The oceans also play a crucial role in the global carbon cycle by absorbing and binding significant amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere dissolves directly into the surface waters of the oceans. In the oceans, phytoplankton use CO2, water and sunlight to grow and reproduce through photosynthesis, releasing oxygen as a by-product. This process removes CO2 from the surface water, which is then replaced by more CO2 from the atmosphere. Some of the carbon absorbed by phytoplankton is transported to the depths of the sea when the organisms die and sink to the bottom. There, the carbon can be sequestered in sediments for centuries to millennia.

However, how much CO2 the oceans can absorb depends on various factors such as the temperature of the water, the salinity and the partial pressure of CO2 in the atmosphere. Colder water can dissolve more CO2 than warmer water - the warming of the seas thus potentially reduces the ability of the oceans to absorb CO2.

Long-term consequences for water sports enthusiasts too

The warming of the oceans is expected to have far-reaching consequences for marine ecosystems. As warmer water can absorb less CO2, the warming of the oceans potentially leads to a lower absorption capacity for carbon dioxide. This can increase the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere and further intensify the greenhouse effect.

However, the rise in sea level is particularly critical - especially for water sports enthusiasts and coastal residents. This also increases the risk of extreme water levels as a result of storm surges, especially on the German North Sea coast. Warmer water can also lead to more intense and more frequent weather phenomena such as strong winds and large-scale or localised severe weather events.

"The influence of climate and ocean warming on the storms themselves is quite complex," says Tim Kruschke from the BSH, describing the situation. "There are cross-relationships, but a large number of factors are decisive." Although the process chain is much more complicated than just the sea temperature on the storms, current research results indicate that, as climate change continues to progress rapidly, weather conditions over the North Sea could also become more frequent, favouring storm surges on the German North Sea coast.

According to forecasts, marine heatwaves will occur more frequently in all oceans. As warmer water can dissolve less oxygen, the living conditions for marine life may deteriorate. With particularly serious consequences for the Baltic Sea: "dead zones" low in oxygen may also increasingly develop on the seabed of the already ailing inland sea.

Regular examinations

The BSH analyses the surface temperatures of the North Sea and Baltic Sea on a weekly basis. The authority combines satellite data with measurements from stationary measuring points and ships. The weekly averages for the months of June, July and August were used to calculate the summer average for 2025 and compared with the summer average for the reference period from 1997 to 2021. This systematic collection and evaluation of marine data makes it possible to recognise long-term trends and document the effects of climate change on the marine environment.

The BSH prepares the analyses as part of the DAS basic service "Climate and Water". Together with other federal authorities, it supports the German Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change (DAS) in order to advise various stakeholders from politics and society.

The BSH will gain further insights into extremes in the sea during a Extreme Weather Congress on 24 and 25 September in Hamburg.