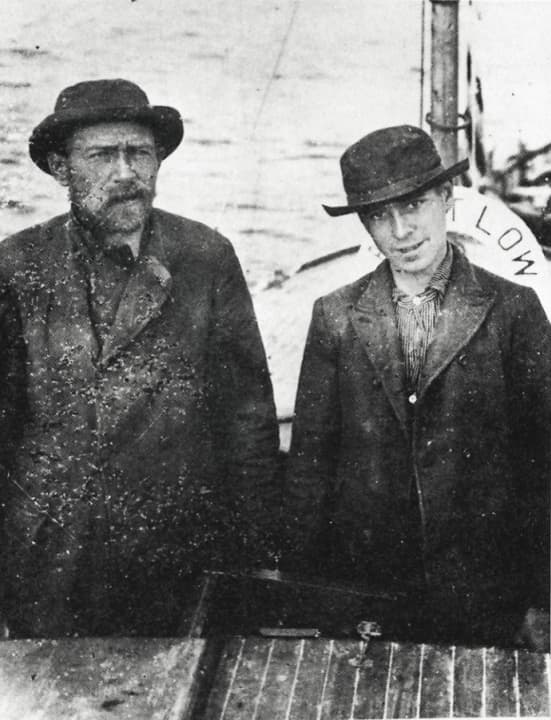

1902: "Abiel Abbot Low"

William Newman and his son Edward are the first to cross the Atlantic in a motorboat. Not out of a thirst for adventure, but to prove the efficiency of combustion engines.

As the beacon of Fire Island sinks behind the horizon, I conceal the feelings that are deep in my heart." These are the succinct words with which Captain William C. Newman ends the first logbook entry of the voyage on 9 July 1902. Not only had he never experienced what lay ahead of him, despite his many years of travelling, but he also knew of no one else in his profession who had attempted a similar voyage. The New Yorker wanted to cross the North Atlantic in a motorboat.

The year was 1902, and although we were hearing more and more about the new motorised carriages - others called them automobiles - on land, people were still reluctant to trust them. Not to mention their use on the water. Internal combustion engine? Doesn't everyone know that it's better not to play with fire on wooden boats? And anyway: far too immature and unreliable!

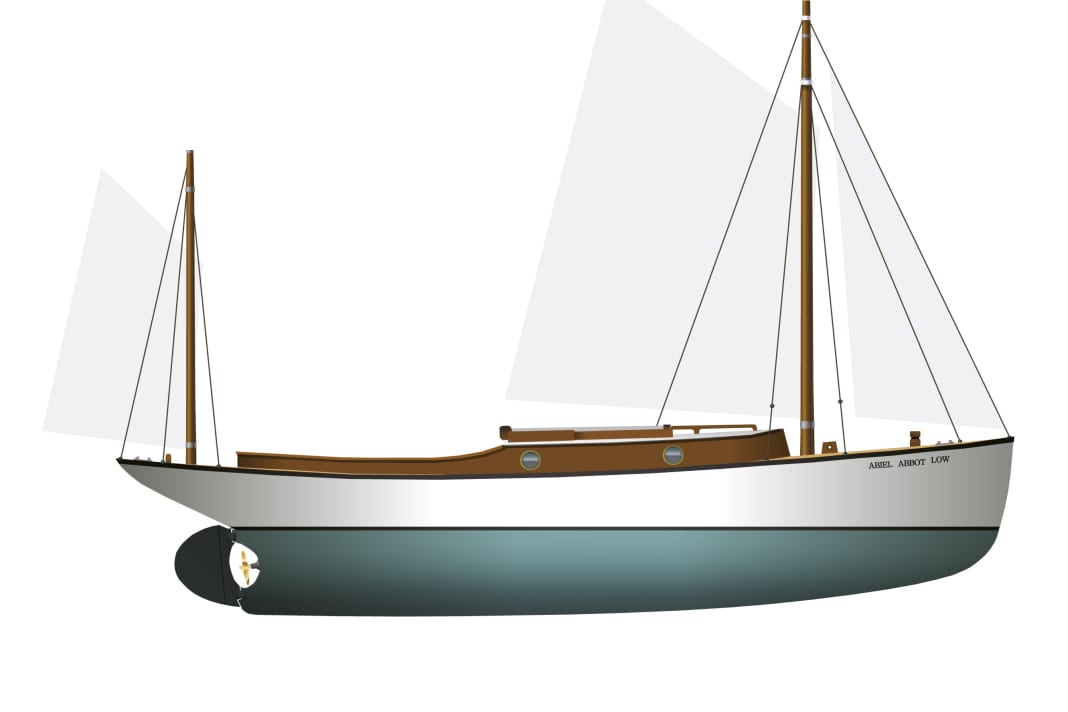

I'm sure this is also on Captain Newman's mind as he looks forward from the tiller, where only open ocean stretches from one end of the compass to the other. The wooden, kravel-planked and fully covered hull is 11.50 metres long, a pointed gate with a decent freeboard. High enough for the wave crests of the North Atlantic? Two short masts rise up for the auxiliary and support sails, no more.

No, the wind will not help him and his 16-year-old son Edward, who is accompanying him. They have to rely entirely on the paraffin engine and its ten horsepower, which rattles along in the cabin below - and hope that the 800 gallons of fuel in the tanks will last until the English coast comes into view.

Because Falmouth in Cornwall is the destination of the journey, some 3000 nautical miles away. There is food on board for 60 days. It shouldn't take that long, but who knows?

Captain Newman is by no means challenging fate out of a thirst for adventure - it is a job for him like (almost) any other. The sponsor of the venture is the "New York Kerosene Engine Company", which wants to prove what its products are capable of. The boat is named after the great entrepreneur (and philanthropist) Abiel Abbot Low.

Summer or no summer, the Atlantic doesn't waste time with pleasantries: On the eighth day at sea, the first storm hits the motorboat, lasting five days. The engine had to be switched off again and again, but the "Abiel Abbot Low" was also working hard on the engine anchor. The paraffin tanks leak and soon the fuel is five inches deep in the bilge, washing through the cabin with every sea. Father and son try to break the force of the waves on the hull with fish oil, but this age-old remedy brings little relief.

Again and again, the wind shifts back and lets the storm run with renewed vigour. Despite their stoic sobriety, the brief logbook entries reveal a lot about the situation on board. 17 July: "Made coffee to warm myself up. Almost at the end of my tether." 19 July: "The hard nights are wearing me out

and my eyes are getting worse." But there is also variety in the monotonous expanse: on 20 July, a passenger ship with four yellow funnels is sighted on a westerly course - it is the fast steamer "Deutschland" of the Hamburg-America Line.

The weather remains bad, despite a few bright spots. "This is the highest sea I've ever seen," notes Newman on the 19th day at sea. "If there's a storm now, our chances will be slim. The hardships are starting to make themselves felt. I'm in a lot of pain."

The leaking paraffin tank also continues to cause problems. Leak detection below deck is hardly possible in the heavy seas. On day 26, the captain writes: "Our clothes are soaked with paraffin and we haven't eaten for 30 hours." Nevertheless, the engine survives all the tests and runs unperturbed.

It becomes a race against time: not because the fuel is running out or the boat is slowly being wrecked, but because father and son are at the end of their tether. And then - almost at their destination - a new danger is added: the exact position. Newman only has a compass on board; without meeting another ship, he doesn't know for sure where he is - and how far away the dreaded cliffs of the Isles of Scilly are. "I have to keep my distance," he decides on day 35. "I reckon we're only 50 nautical miles away from the Scillies and I don't want to take any risks."

Then relief: a fishing trawler is spotted and shows us the way. Even the sun comes out and shines on the last stretch of the long journey, past the Seven Stones lightship, Land's End and the Lizard Head lighthouse.

On 14 August at 6 o'clock in the evening - the 37th day at sea - the "Abiel Abbot Low" enters the port of Falmouth. "Here ends our journey across the Atlantic without a single serious engine failure," concludes Newman. "Everything I have said in this logbook is the truth. I swear it with my right hand, so help me God."

1950: "Half Safe"

The name speaks volumes: Ben and Elinore Carlin fight their way across the Atlantic in "Half Safe", a converted floating jeep from the US Army's World War II stocks. They are almost sunk by their own towing tank.

The direct route across the North Atlantic is also the longest. The northern route from Labrador via Greenland and Iceland to Scotland promises the shortest sea passages. However, bad weather is almost guaranteed there, and ice must be expected everywhere, even in summer.

If you don't trust your boat that much, you can choose the southern route, which leads from America via the Azores and Madeira to the Canary Islands. Ben and Elinore Carlin chose this safe route in 1950 - and rightly so, because the name of their boat, "Half Safe", is actually an exaggeration.

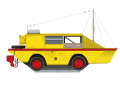

The couple from Australia have set their sights on travelling around the world in a converted Ford GPA - a buoyant jeep of which the Detroit-based car manufacturer supplied around 12,000 to the US armed forces between 1942 and 1943. The amphibian was actually built for crossing rivers or for the short journey from the landing ship's ramp to the beach - but the Carlins want to do justice to the word "seagoing" in the model description. Friends shake their heads, but the two are serious.

However, as cars are not built to drive several thousand kilometres at a time, the fuel tank is already a problem. It holds just 50 litres. However, metal plates are used to weld a boat hull around the 4.55 metre long all-wheel drive vehicle (with a kind of cabin roof on top), which can accommodate any number of additional tanks - for example in the bow or under the floor. This means that 2000 litres of fuel can be stored; a further 1280 litres are to be towed in a floating tank.

The "living area" inside the Jeep consists of a 1.50 metre-long bunk in the rear seat area and the standard driver and passenger seats. While Elinore Carlin can just about squeeze into the bunk, Ben Carlin only has the space behind the steering wheel to sleep. The toilet is also installed under the folding passenger seat.

Although "Half Safe" has a shaft drive and a rudder blade, the vessel can hardly be kept on course without a keel and rolls and lurches extremely at a maximum speed of 3 knots. Elinore Carlin later says that she felt like she was in a washing machine, except that she was getting dirtier and dirtier instead of cleaner.

They set off from Halifax in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and although "Half Safe" was almost rammed and sunk several times by the tank being towed behind, they reached the Azores island of Flores 31 days later - after countless "spin washes".

On the next leg to Madeira, they get caught in a storm that battered the boat and crew for seven days. While the seas beat dents into the boat's thin shell, the engine gave up the ghost several times - only to be brought back to life again and again by the skipper's skilful craftsmanship.

After a further 23 days, the Carlins land on Madeira, briefly at the end of their tether, but far from reaching the end of their journey. After a long European tour, their journey takes them through the Near and Middle East to India. There the couple go their separate ways. Elinore, who will never talk about her time on "Half Safe" again, goes back to the USA. Ben Carlin, however, closes the circle, crossing Asia by land and sea and finally returning to Canada via the Aleutian Islands and Alaska - eight years after the two had set off.

1971: "Red Eric"

In the wake of a real Viking, Hans Tholstrup sets off on the northern route with his day cruiser "Red Eric". He is not afraid of icebergs - he wants to be pulled by them instead.

Compared to the Carlins' Ford GPA, Hans Tholstrup's boat could almost be called seaworthy: in 1971, the Dane tackled the northern route in a 6.10 metre Draco Daycab 2000 - alone, and for the first time ever in a day cruiser.

The idea, writes BOOTE at the time, came to him in the pub over a beer. This is because a brewery in Aarhus sells the "Red Eric" brand, named after "Erik the Red". The Viking was the first to sail from Iceland to Greenland, and his son Leif was even to make it to America - a pioneering feat that Hans Tholstrup would not want to be inferior to.

Of course, the Norwegian Draco with its 90 hp outboard engine also has a problem with range, but with additional tanks for a total of 1400 litres it is increased to 1600 km - enough for the short stages in the north, with one exception.

The Dane takes a relaxed approach to the adventure: He is not afraid of icebergs, he tells a newspaper, he would rather use them to let himself be pulled along. Everything goes well from Copenhagen to Greenland, but the distance from there to Newfoundland is too great - 3200 kilometres, around 1700 nautical miles. To make matters worse, the steering system goes on strike, but a tanker comes to the rescue. The biggest problems during the journey? Tonsillitis and the extra weight from the fuel, because the Draco can no longer glide.

The young Grethe Steen trembled for her fiancé for seven weeks, as BOOTE reported at the time, and continued: "As a reward for keeping her fingers crossed, she received a flight ticket. The story ended like a fairy tale: Hans and Grethe had each other again."

1986: "Virgin Atlantic Challenger"

Billionaire Richard Branson is after the "Blue Riband" for the fastest Atlantic crossing. The first attempt fails, but giving up is not an option!

Richard Branson's success story is a modern fairy tale of a different kind: the resourceful Brit went from publishing his own school newspaper to becoming a billionaire entrepreneur. Now ennobled, his name is behind the Virgin empire with its music shops and airline. However, Branson is always looking for adventure and tackles records, for example in a hot air balloon or on racing yachts.

But it all started with the "Virgin Atlantic Challenger": Branson wants to conquer the "Blue Riband" with an offshore racing boat in 1985 - even though the legendary trophy for the fastest Atlantic crossing is actually only awarded to passenger liners. But he is not interested in the trophy, the record alone is interesting.

The time to beat is three days, ten hours and 40 minutes: The record was set by the liner steamer "United

States" set the record back in 1952 - with an average speed of 35.59 knots. But the ambitious project failed at the first attempt: the "Virgin Atlantic Challenger" sank just 200 nautical miles from its destination in England, but the crew managed to save themselves.

As the word "give up" hardly features in Richard Branson's vocabulary, the second attempt is prepared immediately. The new boat was built using the experience already gained. Just one year later - in the summer of 1986 - the "Virgin Atlantic Challenger 2" was ready for launch. In record time, the

22.02 m long aluminium monohull was completed in record time, with two MTU diesels, each with 2000 hp and surface drives, providing the necessary speed for the three-day sprint. The boat weighs ten tonnes and every unnecessary gram of ballast has been dispensed with. In contrast to its predecessor, however, this time at least recliners have been installed for the crew. Bunks? Not a chance.

The maximum speed is 50 knots, the average at the beginning is "only" 47 knots - to build up a "time reserve". The first tanker is already waiting off the coast of Nova Scotia, 12,000 litres of diesel are taken on board in just over an hour, and the journey continues. But the sea is getting rougher. While the speed barely decreases and the speedboat thunders from one wave crest to the next, the six-man crew feels every start like a hammer blow.

Then, in the fog off Newfoundland, the second tank rendezvous, this time with an oil rig supply vessel. But the "stuff" is bad, white smoke billows out of the exhaust pipes: Water in the diesel! The race against the stopwatch really begins now, everything has to be cleaned. Hardly possible at sea - but the German mechanic, specially seconded by MTU, performs the miracle. Another refuelling and on we go!

More fog, then the darkness of the night; those who get a wink of sleep are lucky. The planes now have to be stopped every hour to change the fuel filters, but the supply is running low. An aeroplane drops supplies.

It's getting close at the end, 600 nautical miles to go. Rain sets in, two of the three navigation systems fail. Then the destination - the Bishop Rock lighthouse and the Isles of Scilly! And the time? "We were two hours, nine minutes and 35 seconds faster than the United States," writes BOOTE employee Dag Pike, who was on board as navigator. "That was close. But what does it matter?"

2009: "I Am Second" and "Gypsy Life"

They want to attract attention to raise money for wounded soldiers: Ralph and Robert Brown are travelling in an open boat from Florida via Greenland to Wiesbaden - and into the Guinness Book along the way.

Even after Richard Branson and the crew of the "Virgin Atlantic Challenger 2" made an exclamation mark, the fascination with extreme cruises across the Atlantic has not diminished. Time and again, motorboat drivers attract attention - and the goal is often another top or first performance. Or an entry in the Guinness Book of Records, as in the case of the American brothers Ralph and Robert Brown, who crossed the Atlantic in an open motorboat in 2009.

With their 6.40 metre catamaran "I am Second" - a so-called flats boat from the shallow waters of Florida - they, like Hans Tholstrup, choose the northern route via Greenland and Iceland and even find time to surf between the icebergs. The board's bag, on the other hand, is alternately used as a sleeping bag - because even the smallest sleeping bunk is taboo for the record entry. "We would never have got real sleeping bags dry," recalls the skipper

Ralph Brown shortly afterwards in the BOOTE interview (see BOOTE 12/2009). "That also applied to sea boots, by the way. Instead, we wore Crocs, those plastic sandals, several layers of woollen socks and even nylon knee-high socks for women underneath. I would never have dreamed that I would wear something like that, but it was the best combination!" Halfway along the route, in the south of Greenland, the American record hunters then meet the German Harald Paul with his 12 metre long "Gypsy Life". Also in spring 2009, he and his wife Silvia set off on their specially converted expedition yacht on their biggest venture to date:

Across the Atlantic to Labrador to then spend the winter in the ice: the Pauls are currently Germany's only extreme skipper couple. They record their experiences with the "Gypsy Life" in books and films.

The "Canadian adventure" leads along the northern Atlantic route to Labrador. Just under 40 kilometres from the nearest town, the two find a suitable bay for wintering in the wilderness. In mid-December, the ice closes around the "Gypsy Life" and only releases it again after five lonely months. (see BOOTE 10/2010) In summer 2010, the Pauls will return to Europe by the same route. However, the Atlantic still holds many adventures in store. The only question that remains is: what's next?