Like an index finger, Denmark's northern tip points high up in Skagen towards the east: please come here if you want to discover a unique area and varied landscapes. A water sports area with lagoons, deep-water pools, shallow bays and fjords that cut deep into the land. Land with vast expanses of dunes reminiscent of the Sahara, with beaches of the finest sand or interspersed with colourful rocks. Plus vast forests, meadows and moors. And people from ten different countries, each with their own culture and history.

Read also:

At the tip of the Grenen peninsula, where white houses surrounded by grasses nestle in the dunes, the North Sea merges into the Baltic Sea, the Skagerrak into the Kattegat. On calm days, this transition seems peculiarly unspectacular, with little more than a narrow fringe of waves jutting out into the sea, playing on the sandbank of Skagens Rev. In the west of the peninsula, we can still feel the DNA of the Atlantic: breakwaters try to slow down the approaching sea, sand moves off the coast under the force of the tidal current and the dunes on land under the force of the wind.

Until we encounter a new world further east: the youngest sea on earth, stretching from Skagen to Kaliningrad, from Törehamn to the Szczecin Lagoon. Surrounded by diverse landscapes, high coasts, flat fringes, dotted with countless islands and skerries. Deep, blue seas with belts and sounds, resting at their edges in fjords and noors, bays and lagoons.

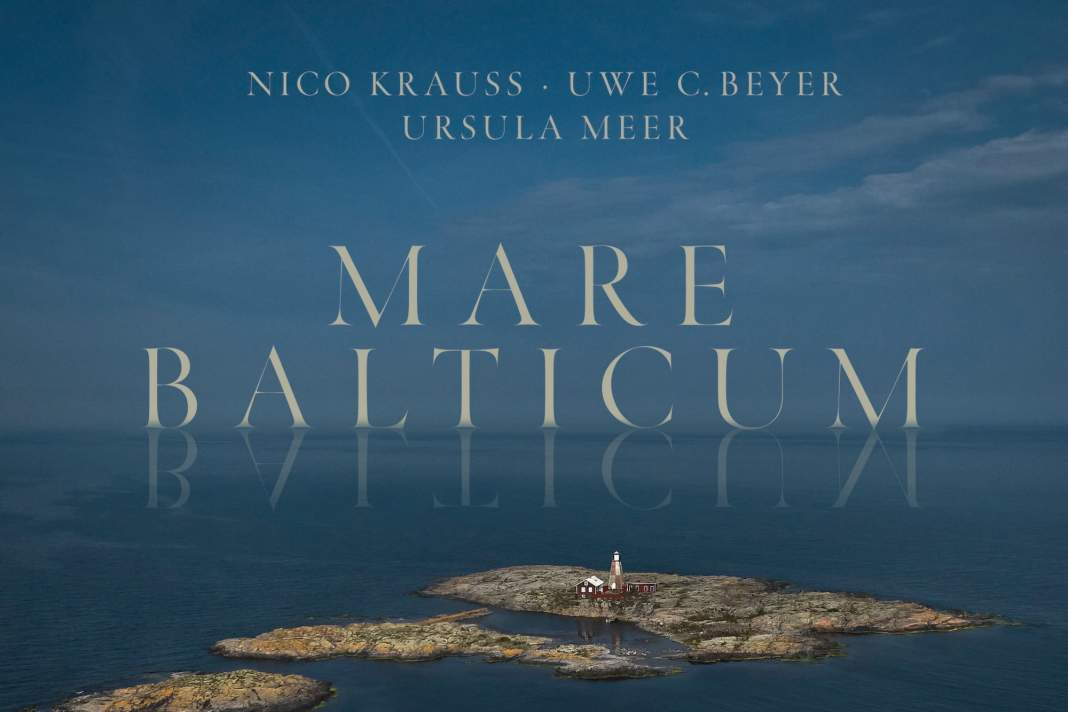

The new illustrated book "Mare Balticum" shows more than 270 fascinating photos by Nico Krauss, the accompanying texts were written by Ursula Meer. 78 euros; shop.delius-klasing.de.

When large waves build up out at sea and become steeper closer to land, they can take anything that is not solid from the seabed on their way to the coast. They carry or hurl it ashore, onto beaches or cliffs, as the mood takes them. There we find chicken gods next to thunderbolts and amber on pebbles, embedded in sometimes coarse-grained, sometimes fine sand. Small clay particles can rest next to huge boulders.

They all tell the story of the last ice age with a dull clinking and scraping in the surf, which 12,000 years ago caused huge glaciers to slowly slide away as they melted, pushing all kinds of subsoil from the far north of Sweden and spreading it southwards and eastwards. It took 4,000 years of rock migration to create the Baltic Sea in its present form. It turned the lower levels of the earth upwards, leaving vertically what had previously rested horizontally below and throwing aside gigantic erratic blocks seemingly carelessly.

The resulting land stretches far out towards the Baltic Sea. In terms of the earth's surface, it is a small but diverse area. In the north, where tectonics pushed large rocks surrounded by smaller ones far out to sea, the water seeks its way through a tangle.

Open water, white cliffs, sandy beaches

So does anyone approaching the land from the sea. Just when we think we are on open water, a flat, shiny crest peeks out here and there. Cormorants and gulls guard the outposts of the mainland, which is barely in sight. The rocks may be rounded by centuries of water washing over them, or they may be dry and karstic. At their edges are traces of long winters in which the frozen sea has scratched them.

The coast rises up dark and karstic with jagged edges of stone peeking out here and there from the sea that glistens at its feet. These islands and skerries seem to have been thrown there at random, overgrown with green or rounded in soft shades of grey, ochre or red, glistening in the sun.

Further south-east, gleaming white cliffs like the chalk cliffs on Rügen and Møn appear before us, waiting to be climbed. Dense forests of pines and oaks grow right up to their edges, some of them clinging on with the last of their strength, already leaning towards the abyss. One day they will rush down into the water, which at our feet is coloured white by the chalk in the sunlight, and behind it is Caribbean turquoise.

The rest was left with a lot of sand by the ice age. It frames the islands in the Kattegat as well as in the Danish South Sea. It separates the coasts from the sea with beaches in all shades of white, gold and grey. In the Baltic region, these beaches stretch for hundreds of kilometres - a huge box seat with a view of a sunset that is rarely found in Europe.

Having barely outgrown its infancy, this meandering continues: The land continues to rise at a slow-motion pace, only perceptible to the human eye for generations. In Finland, for example, where ancient fishermen's houses, once close to the coast, now nestle inland, strangely withdrawn from their purpose and element. Where the land meets the sea, its face is constantly changing.

Wind and weather set the direction

All this diversity, these endearing characteristics, are not enough to give the Baltic Sea its own place in the Seven Seas. It is considered to be an inland sea of the Atlantic and fits into this role by largely dispensing with tidal ranges and tidal currents. This basic reliability makes it equally attractive for visitors on land and at sea. Many come again and again and discover something new even in smaller areas of land. We too have not explored it on one of these long trips around the Baltic Sea. Instead, we have travelled extensively, taking pictures, telling stories and gathering lots of interesting facts about the Mare Baltic - the Baltic Sea, the Skagerrak and the Kattegat.

We visited quiet, remote places, lively, colourful ones and those that oscillate between the two. The wind and weather often dictated the direction, making stages longer, changing course to the next safe harbour or anchorage. They encouraged us to explore small islands in detail, wander curiously through museums and warm ourselves in a sauna.

After all, there's one thing the Baltic Sea can't consistently claim for itself: stable weather conditions and winds. Oilskins and quilted jackets hung in the wardrobe alongside T-shirts and shorts, while boots, hiking boots and sandals found their place on the floor. No item remained unworn, each had its time, even in the height of summer. We didn't always get to the places we wanted to find, but we always got to the places we were supposed to find, on a sea that can change its face frequently and makes good use of it.

It can be grey and wild, calm and dark blue, shallow and deep. In some places, such as the Little Belt, surprisingly strong currents of sometimes more than three knots make the buoys bow to the force.

The salt content of the Baltic Sea is far lower than in the neighbouring North Sea and decreases from west to east, where the rivers feed the sea with fresh water - in the Gulf of Bothnia it is close to zero. This has earned the Baltic Sea the scientific designation as one of the largest brackish water systems in the world. A word that carries with it associations of dull shades of green and a hint of mustiness and does not correspond at all with what the eye sees: deep blue seas in which harbour porpoises show their shiny humps and white-crowned waves through which the sunlight shines golden.