Baltic Sea ship graveyard: Fascinating pictures of ghostly harbour wrecks

Morten Strauch

· 08.03.2025

When a shipwreck is discovered at a depth of eleven metres during a survey of the Trave fairway in 2020, it comes as a great surprise. Researchers at Kiel University investigate the mysterious find. They finally come to a sensational conclusion: it is the remains of a 400-year-old cargo sailing ship from the Hanseatic period, loaded with 150 barrels of quicklime. A unique discovery in the western Baltic region!

Yet the depths of our home waters are teeming with sunken ships. Up to 100,000 wrecks are thought to lie at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, many of which are astonishingly well preserved. The cold water has preserved them better than anywhere else in the world. What's more, there are no shipworm shells in the Mare Balticum that could damage them. For divers and archaeologists, this is a treasure chest full of evidence of past eras.

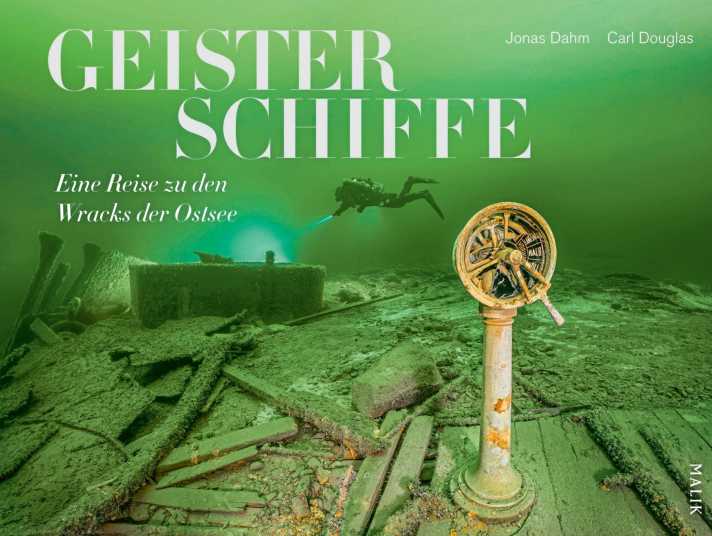

Over the years, a Swedish team has painstakingly located 400 wrecks and brought spectacular images to the surface in numerous dives. The remains of warships,

The remains of warships, merchant ships and passenger ships from the 16th century to the Second World War tell of countless dramas at sea. Some of the documentation can be seen this year in a special exhibition in Helsingør, Denmark.

Also interesting:

Suitable ambience for photos of the wrecks

There is a musty smell of algae and brackish water as you walk down into the historic dry dock, into which the modern maritime museum has been built like a bathtub. The groundwater presses down from below, and in some places the cellar walls move barely perceptibly - it is said that there have been visitors who have become seasick here.

However, the museum is not only remarkable from an architectural point of view. It offers a fitting ambience for the eerily beautiful photos of the shipwrecks. Accompanied by mystical sounds and underwater noises, the exhibition is set in an atmospheric setting. A large wooden rudder, which was found in 2009 during work on the now infamous Nord Stream gas pipelines, is draped right at the entrance.

Strangely, no other wreckage was found there. To this day, it is not known how the rudder got there or which ship it came from. We only know that the wood came from oak trees that were felled in northern Germany in the middle of the 17th century. And that this type of rudder was used on large sailing ships that travelled the seas between the 17th and 19th centuries. Everything else will perhaps remain a secret forever.

More about wrecks:

"Glücksburg" - Anno 1783

More, however, can be learnt about the "Glücksburg", whose underwater image is emblazoned on a huge illuminated surface. The port side of the hull is still standing upright on the seabed. In front of the wreck lies the fallen stem, surrounded by parts of the rigging. The divers found a ship's bell in the bow, which is atypical for an old wooden wreck. Despite its poor condition, the ship's name and "Anno 1783" could be deciphered on the metal.

The wreck lies on hard ground below a slope. Three large anchors, an anchor winch and the presumed bowsprit were discovered at the top. These heavy objects probably mark the spot where the German ship once hit the seabed. It must have slid down the slope from there. A deep furrow runs down to the final resting place.

Between the planks of the destroyed starboard side stands an intact, two-metre-high clay pot. Surrounding it are four heavily rusted iron cannons. What an irony of fate that this fragile jug survived the brutal sinking, while the rest collapsed like a house of cards.

Wrecks with a ghostly appearance

Even more is known about the fate of the regal ship "Svärdet". The Swedish sailing warship served under Admiral Claas Uggla as the flagship in the naval battle off the island of Öland. The enemy was a Danish-Dutch fleet and the battle was for supremacy over the southern Baltic Sea. On 1 June 1676, the Danes succeeded in sinking the two most important ships in the Swedish navy, the "Svärdet" and the "Kronan". Not even 50 of the flagship's crew of at least 620 survived. The wreck was sighted and identified for the first time in 2011. Large bronze cannons, lavishly decorated, can be found all over the three-decker.

The wreck is a ghostly apparition with a well-preserved forecastle. Behind it, it is increasingly disintegrating, the stern no longer exists. It was blown away when the powder chamber exploded, after it had already been stripped of its mast and caught fire. Uggla is said to have refused to have the flag struck until the bitter end and went to sea with his ship.

Surprisingly, a cannon still protrudes from the intact starboard side - a touch of "Pirates of the Caribbean" in the cold waters of the Baltic Sea.

Human tragedies and financial losses

Although it is not possible to clearly identify some of the wrecks, the well-preserved cargo not only tells us something about the once proud ship, but also provides an insight into the era. The "porcelain wreck", as the Swedish divers call it, contains fine ceramics from several manufactories, including Meissen and Fürstenberg. In the 17th century, porcelain became extremely popular with Europe's noble families.

For a long time, the "white gold" was imported from the Far East and was only affordable for the upper classes. It was not until 1710 that the Meissen porcelain manufactory was founded near Dresden. Its trademark, two stylised crossed swords, has attested to the authenticity of the fragile products since 1722.

The unnamed wreck contains other valuable goods such as violin parts, pocket watches and filled inkwells. In addition to the human tragedy, the sinking of this merchant ship must also have been a huge financial loss.

Another wreck surprises us with a number of champagne bottles in wooden crates stored on the upper deck. The labels have long since disappeared, as has the wire mesh used to secure the corks. Many are still in the bottles, but apparently seawater has penetrated: Their contents are mostly cloudy. Some of the bottle stoppers made of Mediterranean cork oak scattered around are labelled "Roederer". The Champagne Louis Roederer house in Reims is still one of the biggest names in the world of exclusive sparkling wine. There are also pocket knives, guns and the remains of indigo bales of cloth. Even back then, merchant ships transported goods of all kinds and origins - comparable to the container giants of today.

Wrecks are perfectly preserved time capsules

On 25 September 1913, however, the "Therapia" set sail from the Finnish port of Rahja with a pure cargo of timber. It was destined for the British mining industry and was to be shipped to Cardiff. A few days after its departure, two of the lifeboats were washed up further south and there was no trace of the crew.

The disappearance of the crew remained a mystery - until they reappeared in Kiel. A Danish steamer was able to rescue the sailors, who were now able to report what had happened to the "Therapia": their ship had collided with an unknown object at night, sprung a leak and sank.

To this day, the freighter remains completely upright at a depth of 70 metres, as if it had been carefully set down there. Apart from some damage to the forecastle, the ship is more or less intact. In addition to the almost complete bridge, it is above all the rooms below deck that leave you speechless. One floor below the upper deck, a long corridor with doors on both sides runs through the entire ship. One of them is open, with the key still in the lock. The cabin behind it apparently housed an officer. Portholes on two walls bear witness to what was once good ventilation and daylight. The original colours can still be seen on the ceiling, walls and wooden details.

In the mess hall, chairs fixed to the floor still invite you to sit down, while drinking and eating vessels and a paraffin lamp lie on a serving table. Finally, the captain's hat - a classic bowler hat - and his uniform with shimmering insignia can be found in the captain's cabin.

The sinking of the "Therapia" had a happy ending in two respects: firstly, the crew was rescued unharmed. Secondly, this ship is a perfectly preserved time capsule that is now accessible to everyone thanks to the impressive photographs.

Interview with Underwater photographer Jonas Dahm

Jonas, how much time did you spend underwater for this project?

We carried out over 800 dives. Many of these were necessary to search for the wrecks and prepare for the photo shoots.

How can such a mammoth project be financed?

I work for the Voice of the Ocean Foundation run by Carl Douglas. The foundation is committed to locating the countless wrecks in the Baltic Sea and illustrating their stories with photos.

What fascinates you most about the Baltic wrecks?

They are incredibly well preserved. There is no comparable place in the world where wrecks that are hundreds of years old are still so intact.

Why is that?

There are none of those nasty boring worms that eat through the wood of the ships. What's more, the water is cold and there are hardly any wreck tourists to tamper with it. The Baltic Sea is not an easy place to dive.

Where did you find the most ships?

The entire Baltic Sea is littered with wrecks and we have been almost everywhere. However, many of the pictures were taken around the island of Gotland, simply because our work boat is based in Visby and the distances are therefore shorter.

Did you change or arrange things on location for the photos?

We have sometimes put a piece of wood to one side, for example over a compass. But apart from that, we've never arranged anything. The wrecks are like time capsules, everything is still there - and that's how it should stay.

How do you achieve such perfectly lit photos in depth?

It's always teamwork with several divers. I work with a tripod and long exposures of up to 20 minutes to capture the last remnants of sunlight even at great depths. We use various flashes and lamps and also play with light painting. We also have a number of other tricks that I won't reveal.

Diving at great depths is very time-limited. How did you go about it?

That's right, at a depth of 100 metres, for example, we only have air for 15 to 20 minutes. Because of the pressure equalisation, we need three hours to get back to the surface safely. This sometimes requires many dives before we have our photos.

Every wreck was a tragedy. How do you deal with it?

Sometimes we actually see mortal remains such as skulls. But when you're diving, you're always focussed on your work and your own safety. In the aftermath, however, some fates are really depressing.

Museum in the dry dock

The premises of the Maritime Museum in Helsingør are remarkable in themselves: at the northern exit of the Öresund, you will come across an extremely exciting mix of historic shipyard architecture and modern design. Embedded in a 19th century dry dock, the museum blends harmoniously into the landscape. The "Hamlet Castle" Kronborg (photo) and the masts of several museum ships moored in the nearby cultural harbour rise up within sight. Including the lightship "Gedser Rev".

From a distance, the Maritime Museum cannot be recognised at all. Only when you stand at the edge of the old dock does the award-winning construction reveal itself. Above all, however, the exhibition itself is worth a visit. Permanent and special exhibitions bring Denmark's maritime history to life. The shipwreck exhibition "Østersøens gåder - Ekko fra dybet", or "Secrets of the Baltic Sea - Echoes from the Deep", can be seen until 15 November. In addition to large-format underwater photographs by Jonas Dahm, artefacts from a warship that sank in 1495 are also on display. The exhibition is rounded off by the works of three artists who have explored the dramaturgy of sunken ships.

The permanent exhibitions also include a model boat collection, which is accompanied interactively in Danish and English. From the marina, the Maritime Museum within easy walking distance. After your visit, it's worth stopping off at the café and museum shop.