Demonstration successful: "If you don't know this and don't have any practice, you'll quickly run aground here or end up on a sandbank!" From the wheelhouse window of his fishing boat, Captain Wilhelm Jacobs points across to a large area of rippled water. On deck, around 20 men and women are looking in the direction indicated. There is a shallow area right next to the Otzumer Balje, the narrow fairway off Neuharlingersiel. It is barely recognisable to the untrained eye. The cutter manoeuvres carefully along the fairway buoys, which lean in the tidal current. It is shortly after low tide and there is not yet much water under the keel of the heavy ship. That is intentional.

Practical training in the Wadden Sea

On this day, the participants of the "Wadden Sea practical training course" are to experience the tidal action with the changing water levels and currents in order to familiarise themselves with them. The course has been organised by the Lower Saxony Motorboat Sports Association for years (LM-N.DE). It is intended as a low-threshold introduction for recreational skippers - whether sailors or motor boaters - who want to get a feel for the Wadden Sea before heading there themselves.

The cutter "Gorch Fock" was chartered in Neuharlingersiel especially for this purpose. Its captain, Wilhelm Jacobs, grew up fishing and knows the area like the back of his hand. "If you don't have enough water under your keel in a fairway like this, it's best to drop anchor in even deeper water in good time and wait," he advises the budding mudflat sailors in view of the shallows. "And if you run out of water, even more so!" Over the next few hours, Jacobs will pass on much of his wealth of experience to the recreational skippers.

Theory and practice combined

They are already well prepared in theory. The day before, course instructor Ute Gausmann taught them everything they need to know about navigation and seamanship in the tidal area of the German Bight. She has largely dispensed with electronic aids, because "the participants should really understand what is happening in the tidal area in order to be able to navigate there safely," explains Gausmann. "If the echo sounder suddenly goes to zero, I have to be able to assess the situation: Has the current shifted my boat, has the wind caused the water level to drop, or am I simply too early at the high tide?" she says, describing possible scenarios. Only then can you quickly decide what to do. "In such a case, no app will tell me whether I need to change course or anchor!"

A teacher by profession, Gausmann explained to the water sports enthusiasts in the one-day theory session how to use the necessary tools such as tide tables, charts and forecasts and methodically imparted basic knowledge about navigating the mudflats: Water levels and current, meandering sands and plumbed depths, wind direction and strength. Calculation formulae on the blackboard, chart depth, sounding and height of tide on the flipchart.

Testing the calculations in practice

The many variables that have to be taken into account when planning a mudflat trip caused the participants to frown a little. The course instructor patiently answered all the questions. With success: that very afternoon, everyone was able to calculate how much water the cutter should have under the keel off Spiekeroog, Langeoog or Baklegde on Sunday.

Now it has to be seen in practice whether the calculations are correct. The extended cutter trip starts in Neuharlingersiel and leads through the tideways of the Otzumer Balje towards Spiekeroog and on into the Seegatt as well as to Langeoog and Bensersiel. That is far more than a pleasure craft usually leaves in its wake in one day in this area.

"We can't moor on one of the islands today, otherwise we won't be able to get back via the Prickenweg later," says one of the participants from the previous day's calculations. After all, the cutter has a draught of 1.50 metres. So now it has to turn round in the mudflats in view of the nearby Wadden High and sets course for Spiekeroog.

Navigation challenges in the mudflats

The entrance to the small island harbour makes a small curve and is marked on both sides with pricks. As they approach, they all seem to stand next to each other, almost like a hedge. At the railing, the inquisitive passengers squint their eyes - until the apparent row visually dissolves as they approach. Individual gate peaks become recognisable, with green barrels next to them: The confusion becomes a path. "You have to see this! With my own boat, I would have been worried for a moment that we'd miss the entrance!" murmurs one of the participants.

The journey continues into the Seegatt between Spiekeroog and Langeoog. The North Sea outside, the Wadden Sea inside. If you want to travel from one island to another, you have to head quite far north in the Gatten towards the open sea. Today, initially against the current. Captain Jacobs sails a little to the east, outside the buoyed fairway. "We're taking the Neerstrom with us here. This is a current running in the opposite direction to the main current. That way, we don't have to move against it as much," he explains. And immediately warns: "We know from experience that it's deep enough outside the fairway here. But you should never attempt this without having enquired first!" If the wind is against the tide, a veritable wave can build up in the Gatten. Groynes protrude far into them. Next to the cutter, whirlpools make the surface of the water look like huge, spinning plates; it's easy to imagine that things can get quite adventurous here and a pleasure craft can quickly be displaced.

Adaptability of the sea slips

"The sea races are constantly changing," explains Jacobs, "every year, sometimes even within a few weeks." He and his colleagues have already pulled many a boat off the sandbank.

On the approach to the Langeoog mudflats fairway, he changes course to the south-west. The current, which is now travelling with him, causes the log to shoot up by two or three knots - a veritable jet effect at the edge of the mudflats. Seals snooze on a sandbank to starboard, behind them the surf foams on the waves rolling in from the open North Sea. They seem close enough to touch, with only a few hundred metres separating the fairway from the sands.

At the buoy line, the cutter navigates safely towards the Prickenweg. At first, the narrow birch trunks stand out only dimly against the cloudy sky. Their branches point upwards, which characterises them as port prickles. But the cutter has them on its starboard side. A passenger is puzzled for a moment: "If we're coming through the Gatt, wouldn't that be 'coming from the sea' and the pricks should be on the port side?"

Precise navigation required

Ute Gausmann hears this question frequently. She refers to what she learnt in theory the day before: "Do you remember the arrows with red and green dots on the nautical charts? They indicate the buoyage direction. Here it's from west to east." Lively nodding; there's a lot to remember when travelling on the mudflats.

Sediment-clouded water flows around the pricks. Everyone on board knows that it is now getting steadily shallower under the cutter. But nothing can be seen. "Without an echo sounder, you're really lost here," realises one of the participants as he looks over the railing. The fact that Ute Gausmann has not exaggerated when listing the necessary equipment for the mudflat trip - anchor, throw anchor and depth sounder, for example - becomes clear when looking at the opaque water. It also raises the question of where it is best to sail in the mudflats: rather close to the pricks or at a certain distance?

It's not always possible to say exactly where the prick paths are deepest," explains the cutter captain. "But there is a rule of thumb: on the seaward side - i.e. where the water from the mudflats flows into the mudflats - the edge is often steeper. That's where you'll usually find the deepest water very close to the pricks." Further inland in the mudflats, the tidal flat is often shallower and wider. "You should keep a little distance from the tideways there because the deeper line doesn't run directly next to the markings." Where the currents coming in from both sides meet is where the shallowest parts of the mudflats are found, the so-called Wattenhochs.

Seasonal conditions in the mudflats

On this somewhat cloudy day in April, there is still little going on in the area. However, the mudflats appear quite narrow: it is easy to imagine that it could get crowded in the summer when more ferries and mudflat sprinters call at the islands, sailors and motorboaters wind their way along the tideways and fishermen go about their work.

Another cutter is approaching on the opposite course. Around 100 of its kind are still actively fishing in the Wadden Sea with nets around 17 metres long, which are kept open at the sides with ten-metre-long trawl poles. Accordingly, sufficient distance should be kept from fishing cutters.

Will that fit in the narrow waters? But the oncoming vessel is one of the many excursion cutters with guests on board. The two large vessels can easily avoid each other as long as one eye is always on the echo sounder. Although both are more than four metres wide, they do so at a good distance; the fairways are wider than expected.

Safety aspects in the fairway

Standing at the helm, Captain Jacobs explains: "You always have to keep enough distance, especially when encountering ferries or a cutter. They displace a lot of water and create strong suction effects. We once experienced our cutter being sucked in so strongly by a passing ferry that we almost collided." And this despite weighing many tonnes; it is easy to imagine how a light pleasure craft might fare in such a situation.

According to the captain's tip, it is best to always behave clearly in narrow waters by signalling course changes in good time and, if possible, giving way to starboard for oncoming vessels. "But," adds the professional with a wink, "if you give way too early, you'll tempt the other person not to make any course correction at all."

Protected by a high wall with a wide opening, the harbour of Langeoog appears more spacious than the sedate island harbour of Spieker oogs. But on the starboard side, the piers point the way in a wide arc. The harbour area behind it now, near high tide, does not differ visually from the one in front. However, it dries out at low tide - a peculiarity of island harbours.

On the way back, we take a short tour of the lively harbour of Bensersiel on the mainland before heading back to Neuharlingersiel across the mudflats just below land. For the first time during the trip, the wind and current oppose each other over the last few miles. Short, steep waves make the 15-metre cutter really roll.

Respect for the mudflats is important

Course leader Ute Gausmann thinks that's a good thing: "It's important that the participants see how quickly the situation in the Wadden Sea can change. They shouldn't be scared, but they should have respect - and be prepared accordingly." The calculation works. One of the participants turns to her and says: "It could be quite bumpy here with our little boat. But it's doable - and exciting and fun at the same time!"

Handy: The rule of twelve

In contrast to most other tidal areas, the tide in the German Bight runs in the form of an equally moderate parabola. This makes it easy to calculate the water level for the individual hours of a tide using an approximation formula, the rule of twelve. This is how it works:

- Divide the tidal range, i.e. the difference between low and high tide, by twelve.

- The simple rule of thumb is: 1-2-3-3-2-1, which means that in the first hour after low tide, the water rises by one twelfth of the total tidal range, in the second by two, in the third and fourth by three twelfths each, in the fifth by two and in the sixth by one twelfth again.

- After flooding, the water falls according to the same pattern.

- As the tidal range or fall is highest at hours three and four as well as nine and ten of a tide, the strongest current must also be expected at these times.

- Furthermore, the water levels are subject to daily influences due to wind, air pressure and the age of the tide (neap, mid and spring tides). A persistently strong easterly wind, for example, can reduce the water level. Therefore, allow a reserve of 50 centimetres when passing the shallowest points.

Equipment & navigation for the Wadden Sea

The recommended equipment for the mudflat trip includes

- An echo sounder, a main and, if possible, a second anchor as a throw anchor. This allows you to react quickly if the boat threatens to drift onto a flat or if there is not enough water over a flat.

- For navigation, the BSH tidal calendar and current, corrected nautical charts.

- A pocket calculator, sailing guide and yacht radio service are recommended.

- In the harbour, long lines are useful for the packet, and fender boards on sheet piling.

- The Wadden Sea is very changeable. The depth information in the nautical charts is not always reliable. The Wadden sailors therefore help themselves: They sound the water depths in the mudflats at mean high tide and publish them on their website (WATTSEGLER.DE). There you will find further information about the area.

- Navigation apps and tide calendars provide information about the tides and their heights, but without taking into account current weather influences such as wind and air pressure, which can affect the height of the water level. The daily forecasts from the BSH are therefore more reliable (BSH.DE).

Guide for water sports enthusiasts

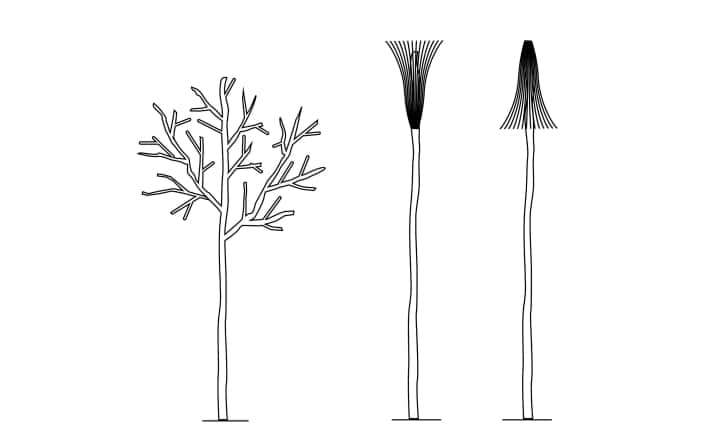

Pricks mark the narrow mudflats. Port pricks can be recognised by tufts of brushwood or branches fanned out at the top. Starboard pricks have a tuft of brushwood fanned out at the bottom. Two pricks close to each other stand on a tidal flat, three next to each other mark the beginning and end of the prick path.

Anchoring & falling dry

With the right boat, you can easily fall dry in the mudflats. However, please note the following points:

- Look for a place with a flat, sandy bottom and not too close to fairways or channels.

- Check the condition of the bottom and above all the depth with an echo sounder and boat hook.

- Choose the location carefully: If you fall dry higher, i.e. shortly after high tide, you won't have water under your keel again until later.

- If everything fits, drop the anchor and wait for the boat to sink slowly.

- Keelboats can anchor at the edge of some of the tideways around the islands.

- Due to the current, make sure you have good anchor gear and enough chain. The water rises and falls by three to four metres.

- Beware, the boat will later drift in the opposite direction when the water rises.

- If there is no strong wind across the current, the boat can be anchored with two anchors and a riding weight against both directions of the current.

- Pay attention to the weather. If the wind is against the current, things can get rough at anchor; dry boats can hit the bottom in a rising wave before they float up again.

These rules apply in the mudflats

More about the navigation rules find out here.