"Dangerous current! Very rough sea!" warns the nautical chart of the Passage du Fromveur, the notorious strait south-east of the Île d'Ouessant. Coming from the east, a long Atlantic swell can provide skippers with a very pleasant journey across open sea. In Fromveur, however, the path between Ouessant in the north and the many small islands in the south narrows. And what juts out of the water so steeply and high is an extension of what lurks underwater: countless rocks and shoals over which considerable masses of water flow, twice a day from east to west, from west to east.

"Whoever encounters the Fromveur, encounters fear" is the traditional wisdom not only of Breton sailors. It is not least such descriptions that characterise the reputation of the Île d'Ouessant to this day: unapproachable, wild and dangerous. But also: shrouded in legend, mysterious. It seamlessly joins the ranks of places that have been shrouded in countless myths for centuries and have left sailors in awe: the dreaded Cape Horn, the irrepressibly swirling Moskenstraumen near the Lofoten Islands, the almost inaccessible Easter Island or the north-east and north-west passages in the Arctic latitudes, which even these days can only be conquered in exceptional circumstances. Few dare to head for these and similar destinations. However, those who take up the challenge are often rewarded with a unique experience that lasts a lifetime. All the vague myths suddenly give way to real impressions, experiences and encounters. They make you forget the hardships of the journey.

Fromveur - swell against tides and wind

The Île d'Ouessant, a place with a very special charm, is no exception. It is the island of sailing records, lighthouses and women. This small island of delicate magic on the edge of the Bay of Biscay and with a veranda view of the Atlantic - it needs to be discovered and conquered with care.

"The particular pitfall of this strait is that, in addition to the tidal current and the wind, the swell from the Atlantic also gets involved. When an old, high swell flows in from the north-west and the ebb current and possibly the wind set against it, it can be really dangerous," says Wilfried Krusekopf, describing the fromveur.

The German has lived and sailed in Brittany for decades, he is the author of nautical and sailing books and a recognised expert in tidal navigation. "But you need the ebb current if you want to come through here from the east," he says. "On the other hand, if you have the current against you, you can be overtaken by a buoy - if it's visible. Because dense fog is also quite common." A good five nautical miles through the strait can then become a lengthy and uncomfortable endeavour.

But when the tide and weather are right and a window opens for the passage, when the current and wind are travelling in the same direction and the Atlantic is not rolling the after-effects of the last storm into the strait, then it is really fun. Then the short stage turns into a fast and yet safe episode - like in a lively whirlpool, in which tidal rapids drive the journey over ground to astonishing heights and huge whirlpools make the compass needle rotate. Then the destination, the Île d'Ouessant, is reached almost too quickly and the boat enters the Baie de Lampaul, the sheltered bay to the west. A huge rock juts out of its centre in solitude. Mooring buoys are laid out for mooring, there is no marina. Cormorants guard the entrance. Occasionally, dolphins even find their way into the bay.

The bay of Lampaul as a place of refuge

The same goes for the Atlantic swell. Although quite well protected from the wind, a constant swell rolls in from the open sea. The masts of the yachts dance ballet in an inconsistent choreography. Some sailors are simply seeking shelter from a storm here, others a quiet night after crossing the Bay of Biscay. You can see what some of them have been through as they clumsily and exhaustedly tie up to the mooring line, only to fall exhaustedly into their berth immediately afterwards. The island shore is not far away with the dinghy - at high tide, simply cross over; at low tide, it is better to stick to the buoyed fairway if you want to enjoy your dinghy for longer. A staircase at the old jetty is both a step up and a cleat.

Next door, in the small fishing harbour, boats are moored on dry land, each with a long line to the steep coast. Rusty ladders lead far down at low tide. Ships on a line are the local alternative to elaborate harbours. Even in the rather moderate summer, you can imagine how insensitive you have to be to heights, cold, wet and waves to get to your boat and go out here day in, day out.

The houses of Lampaul, the island's capital, stand close together on hills with narrow streets. They are built from the same grey granite on which they stand, colourfully framed by hydrangeas and asters, St. John's wort and lilies. Tourists linger in small shops and bistros with a view of the street life or the coast. Waiters with Nordic charm serve oysters and mussels, beer, wine and cheese. The village church watches over everything almost majestically.

The cliffs are just a few steps away from the village. Seen from the sea, it looks rather rocky and sparsely vegetated. However, hikes alternate between karstic rock and soft greenery, interspersed with flowering heather, dense grass and wild herbs of all kinds. The vegetation hides from the wind, trees grow almost exclusively in gardens. Some paths lead narrowly along steep cliffs, others across meadows and whole fields full of ferns.

The water is deep green, azure blue and turquoise at the edges

Changeable weather always brings new sights: subdued in the dull light, it shines in all colours on land as soon as the sun breaks through for a brief moment. The water in the bay then turns deep green, azure blue and turquoise at the edge. The high coast also allows a view into the distance, to the north into the distance, to the south across the strait and the offshore islets to the mainland.

It is hard to imagine that shipping traffic between northern and southern Europe travelled through this passage until the 1980s. It must have been the accident involving the oil tanker "Amoco Cadiz", which wrecked on a rock east of Ouessant in a storm and caused an oil spill of gigantic proportions, which led to a rethink. The island itself and the surrounding sea area are now a UNESCO biosphere reserve. Traffic separation schemes and shipping lanes run a fair distance from large algae fields and the habitats of dolphins and seabirds.

Small settlements with equally small farms characterise the island's interior. Stone ruins tell of the hardships that life was once full of where holidaymakers relax today. The former fields are surrounded by rough walls, and the wind probably left no seed to germinate. As the men went to sea, it was the women of Ouessant who cultivated these fields. They must also have been the ones who gave the windows and doors of the houses their fresh blue colour. It stands out everywhere on the old buildings against the grey-brown rock: Sea, sky and rock united in facades. But also the message: "Return!" Because blue symbolises Mary, the patron saint of sailors. Nevertheless, many remained at sea. Small wax crosses were then buried in their place. "Proella - back on land" was the name given to these witnesses to mourning, which were placed in a mausoleum in the cemetery, barely higher than the crosses around them. Some are said to be from the 13th century.

Day tourists hike and cycle across the island

From the sea, the coast in the north-east is the most impressive. It rises high and steep. At the top is the pretty Phare du Stiff, the oldest lighthouse in Ouessant. On the cliffs, a lonely house that looks as if it is about to plunge into the depths. Below it, mooring buoys lie in the bay, with the ferry harbour right next door. The harbour makes every effort to conceal the charm of the island. A concrete terminal, a few scattered houses and plenty of storage space exude pure practicality. Boatloads of day tourists are landed, quickly spread out across the island on foot or by bike and return to the mainland from here in the evening.

But just behind the next headland, just one cardinal buoy further on and a short turn from Fromveur, Port d'Arlan is already glowing in all the bright colours that a perfect day's holiday needs. A wide beach with a single mooring buoy in front of it. If you arrive in time, you have a very private spot for the night; there are no neighbours and anchoring is prohibited. Rocks and seaweed are exposed at low tide, opening the way to another beach. If you doze off here, you have to wait until the next low tide. It is correspondingly quiet.

The western end of the island, on the other hand, offers pure landscape drama. High, pointed rocks jut out against the sea in a peculiarly rugged manner. A lot must have meandered millions of years ago when the layers of rock folded diagonally towards the sky. It's a good 2000 miles to Newfoundland from here. The sea can gather, rise and pile up before crashing in with all its force. Sea and island compete to be the most beautiful at the "Finistère", the end of the world, as those who didn't know any better called it.

Five iconic lighthouses to guide navigation

The ships passing by in the distance look tiny; skippers respectfully keep their distance. Many crews have met a bad end here, at the western tip of France, at the entrance to the English Channel. To prevent this from happening, the Phare du Créac'h stands high above the roaring spectacle, straight as a die, ringed like a Breton shirt.

A favourite family photo backdrop, it is also known as the "Eiffel Tower of Île d'Ouessant". It sends its light 32 miles out to sea, further than any other lighthouse in Europe. In addition to it, there are four other lighthouses that guide sailors around the island and its treacherous shallows - a remarkable density of light, even for Brittany. Where, if not here, is it worth taking a closer look at the history of night-time navigation?

The Phare du Créac'h houses an exciting museum inside. With fire baskets, oil lamps and man-sized, carefully cut Fresnel lenses, it shows the development of the scope of light over the centuries in fast motion. It first shone from the towers of abbeys and churches, later from towers on land and finally at sea.

The monks, who lit the first fires on their church towers to show sailors the way, wanted to be close to heaven. Later, it was less convenient to work in the real lighthouses, which were built at great expense on rocks far off the coast and could only be reached by ship. Frequent shift changes were forbidden simply because of the dangerous journey to work.

La Jument lighthouse and the world-famous photo

For weeks, the guards remained alone with their lenses and lights, between alcove beds and cupboards, angularly fitted into the round, a table, a chair. They kept watch, made repairs and communicated with the outside world by radio while the surf gnawed at the base of the tower and gusts whistled around the masonry. It is hardly surprising that these towers in the sea were called "hell" by their inhabitants, those on uninhabited islands "purgatory" and those on land "paradise". The career ladder led from the former to the latter.

La Jument lighthouse, just under a mile off the coast, is another such "hell". Its keeper, Théodore Malgorn, came very close to becoming fatal. When he heard the roar of a helicopter in December 1989, he stepped outside the door of the tower. A huge wave roared behind him and burst white and foaming like angels' wings at the back of the tower. The photographer in the helicopter, Jean Guichard, pulled the trigger at that precise second and took the photo of his life, while the lighthouse keeper below unwittingly risked his own. Here, at the end of the world, the path between hell and heaven is often just a narrow ridge.

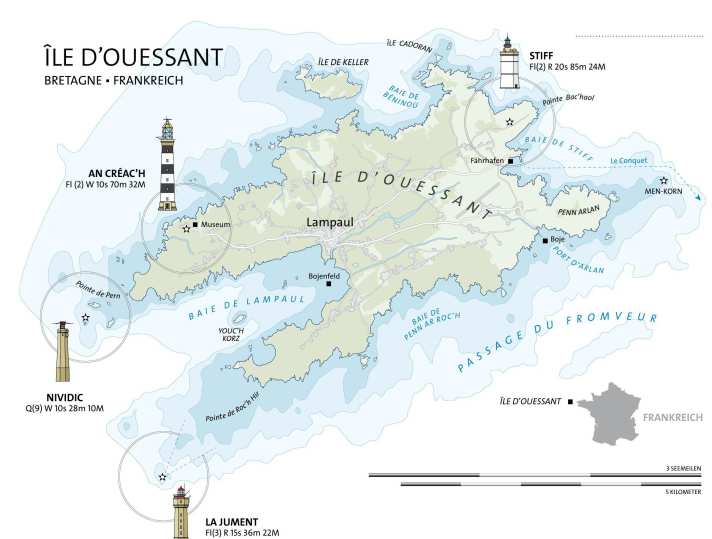

Les Phares: The lighthouses off Ouessant in Brittany

The island is of outstanding importance to seafarers - in the past as an often tragic obstacle, today as a navigation marker by day and night. A number of serious accidents in the dangerous and busy sea area off Ouessant led to the construction of several lighthouses. They are spread around the island and are still in service today.

- The brightestis the Phare du Créac'h (also known as Ushant Lighthouse), built in 1863. No lighthouse in Europe surpasses the scope of its light. Coming from the Bay of Biscay, it is the first visible lighthouse and the most important sea mark for entering the English Channel. Height of fire: 70 m, range: 32 nm

- The most famousThe Phare de la Jument, built on a rock off the coast in 1904 and in operation since 1911, was built following an accident on the cliffs off Ouessant in 1896, which claimed the lives of 243 people with only three survivors. It was here that the famous photo of the lighthouse keeper was taken, with the waves crashing down behind him. Height of fire: 36 metres, range: 10 nm

- The eldestis the Phare du Stiff. It was completed in 1700, making it the oldest lighthouse on the French side of the English Channel. All shipping traffic in the surrounding sea area is also monitored via a transmitter next door. Height of fire: 85 metres, range: 24 nm

- The most unusualis the Phare de Nividic, built on the open sea between 1912 and 1936. After only four years, its light went out at the beginning of the war. It was only relit in the 1950s. The lighthouse keeper initially reached the tower by cable car, later by helicopter. Height of fire: 28 metres, range: 10 nm

Area information Île d'Ouessant

The island of Ouessant(BretonEnez Eusa,EnglishUshant)belongs to Brittany and lies a good ten nautical miles off the coast on the northern edge of the Bay of Biscay. The westernmost settlement in France - apart from the overseas departments - marks the western entrance to the English Channel, just like the Isles of Scilly on the opposite British side.

Celts, Romans and Christiansfound their way here. They left their mark on the language and culture, as they did everywhere in Brittany (Breton:Breizh):Christian crosses can be found on churches, and triskele can be seen everywhere else. These swirling, three-armed crosses symbolise the three elements of earth, fire and water - the Celtic heritage of the Bretons.

If the residents livedFormerly dependent on fishing, seafaring, smuggling and agriculture, today it is mainly tourism and services that ensure a modest livelihood. Most holidaymakers only visit the island for a day and there is little accommodation. The number of inhabitants is steadily decreasing; in 1968 there were just under 2000 people, but today around 800 live here - in summer. Many spend the winter on the mainland.

Skippers can use their yachtsmoor at mooring buoys in the Baie de Lampaul and the bay near the ferry harbour. The island does not have a marina. There are shops in the island's capital Lampaul. There are also a number of pretty bistros and good restaurants.