The main advantage of a long-sided berth is that you don't have to squeeze into a box first. You can moor up quickly and - if you wish - leave again quickly. So it's perfect for a short stop to take someone on board, for shopping, eating or bunkering. But of course you can also stay alongside for longer. The following pages describe how the mooring manoeuvre takes place in such a place - and it depends not only on external factors, but also on the boat and the type of propulsion. Important: If you are not yet fully familiar with the boat, the length of the mooring should be at least twice the length of the boat.

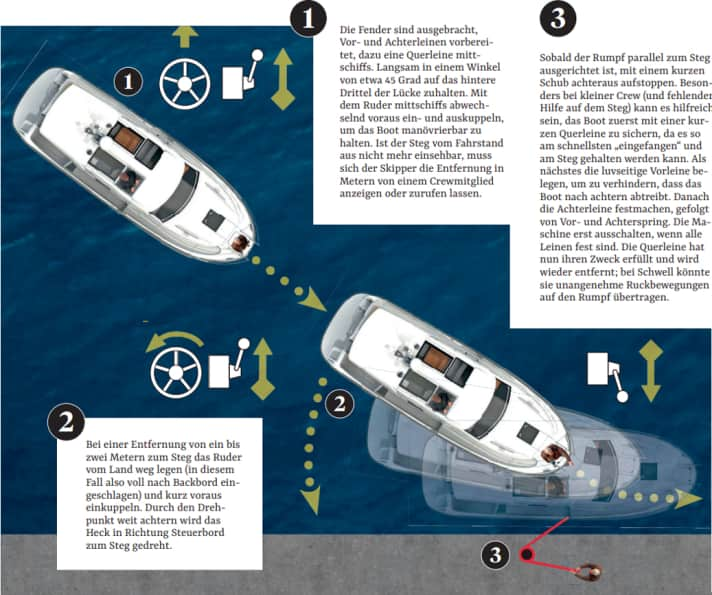

With shaft drive

Step 1

The fenders are deployed, fore and aft lines prepared, plus a transverse line amidships. Slowly manoeuvre towards the rear third of the gap at an angle of about 45 degrees. Alternately engage and disengage the rudder amidships to keep the boat manoeuvrable. If the jetty can no longer be seen from the helm, the skipper must have a crew member indicate or call out the distance in metres.

Step 2

At a distance of one to two metres from the jetty, turn the rudder away from the shore (in this case fully to port) and engage the clutch just ahead. With the centre of rotation far aft, the stern is turned towards the jetty on the starboard side.

Step 3

As soon as the hull is parallel to the jetty, stop with a short push aft. Especially with a small crew (and no help on the jetty), it can be helpful to secure the boat with a short transverse line first, as this is the quickest way to "catch" it and keep it on the jetty. Next, attach the windward lead line to prevent the boat from drifting aft. Then tie up the stern line, followed by the fore and aft spring. Do not switch off the engine until all lines are secure. The transverse line has now fulfilled its purpose and is removed again; in swell it could transmit unpleasant jerking movements to the hull.

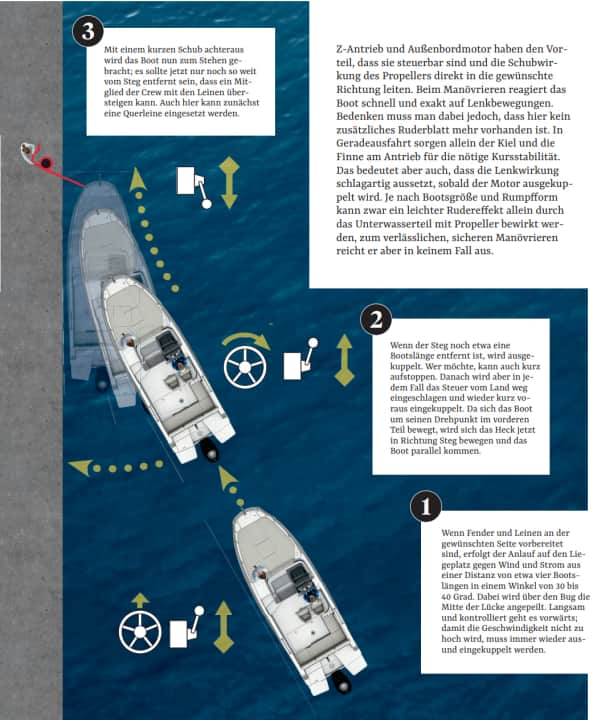

With Z-drive and outboard motor unload and load

The advantage of the sterndrive and outboard motor is that they are steerable and direct the thrust of the propeller in the desired direction. When manoeuvring, the boat reacts quickly and precisely to steering movements. However, it is important to remember that there is no additional rudder blade. When travelling straight ahead, the keel and the fin on the drive alone provide the necessary course stability. However, this also means that the steering effect stops abruptly as soon as the engine is disengaged. Depending on the size of the boat and the shape of the hull, a slight rudder effect can be achieved by the underwater part with the propeller alone, but this is never sufficient for reliable, safe manoeuvring.

Step 1

Once the fenders and lines have been prepared on the desired side, the approach to the berth is made against the wind and current from a distance of about four boat lengths at an angle of 30 to 40 degrees. The centre of the gap is aimed for via the bow. The boat moves forwards slowly and in a controlled manner; to prevent the speed from becoming too high, the clutch must be disengaged and reengaged repeatedly.

Step 2

When the jetty is still about a boat's length away, disengage the clutch. If you wish, you can also stop briefly. Afterwards, however, the rudder is always turned away from the shore and reengaged shortly ahead. As the boat moves around its centre of rotation at the front, the stern will now move towards the jetty and the boat will come parallel.

Step 3

The boat is now brought to a standstill with a short push aft; it should now only be far enough away from the jetty for a member of the crew to cross over with the lines. A transverse line can also be used here first.

Further topics for beginners:

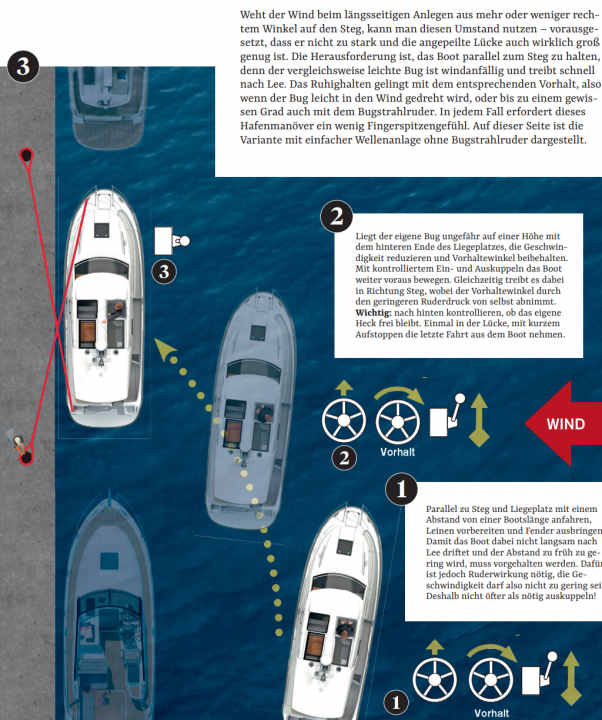

Onshore wind: take off and moor with shaft drive

If the wind blows from a more or less right angle onto the jetty when mooring alongside, you can take advantage of this - provided that it is not too strong and the gap you are aiming for is large enough. The challenge is to keep the boat parallel to the jetty, as the comparatively light bow is susceptible to wind and drifts quickly to leeward. Keeping the boat calm is possible with the appropriate lead, i.e. by turning the bow slightly into the wind, or to a certain extent with the bow thruster. In any case, this harbour manoeuvre requires a little dexterity. This page shows the variant with a simple wave system without a bow thruster.

Step 1

Approach parallel to the jetty and berth at a distance of one boat length, prepare the lines and deploy the fenders. To prevent the boat from drifting slowly to leeward and the distance becoming too small too soon, you must keep ahead. However, this requires rudder action, so the speed must not be too low. Therefore, do not disengage the clutch more often than necessary!

Step 2

If your own bow is approximately level with the rear end of the berth, reduce speed and maintain the lead angle. Move the boat further ahead by engaging and disengaging the clutch in a controlled manner. At the same time, it will drift towards the jetty, whereby the lead angle decreases automatically due to the lower rudder pressure. Important: check to the rear to ensure that your own stern remains clear. Once in the gap, take the last drive out of the boat with a short stop.

Step 3

Ideally, the boat will now be almost parallel when it drifts with the leeward side onto the jetty. But even if the alignment is not quite perfect, the wind will do the rest by itself. The main thing is that the entire side of the boat is well fendered. Handing over the lines or climbing over is no longer a problem.

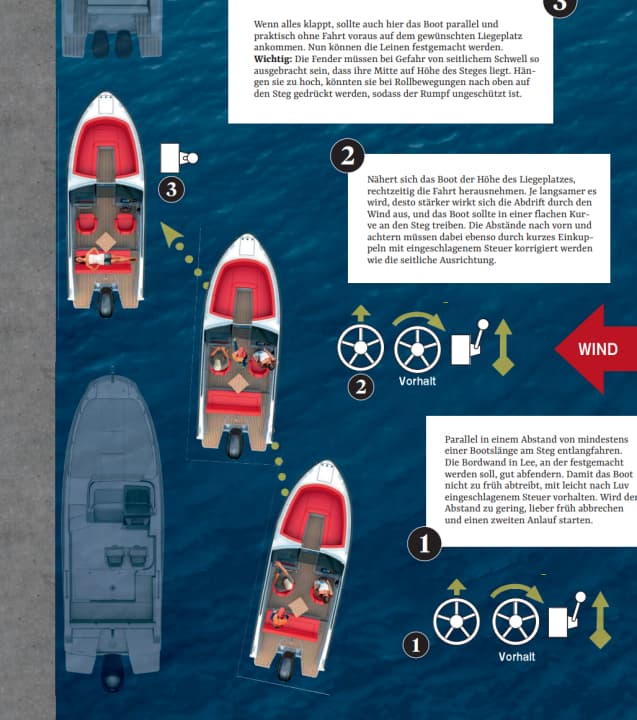

Onshore wind: with sterndrive and outboard motor

Step 1

Travel parallel to the jetty at a distance of at least one boat length. Anchor the leeward side of the boat to which you want to moor. To prevent the boat from drifting too early, keep the helm turned slightly to windward. If the distance is too small, it is better to abort early and make a second attempt.

Step 2

As the boat approaches the mooring, slow down in good time. The slower it gets, the greater the drift caused by the wind, and the boat should drift in a flat curve towards the jetty. The distances forwards and aft must be corrected by briefly engaging the clutch with the helm turned in, as must the lateral alignment.

Step 3

If everything goes well, the boat should arrive at the desired berth parallel and practically without travelling ahead. The lines can now be tied up. Important: If there is a risk of side swell, the fenders must be positioned so that their centre is level with the bridge. If they are too high, they could be pushed upwards onto the bridge during rolling movements, leaving the hull unprotected.

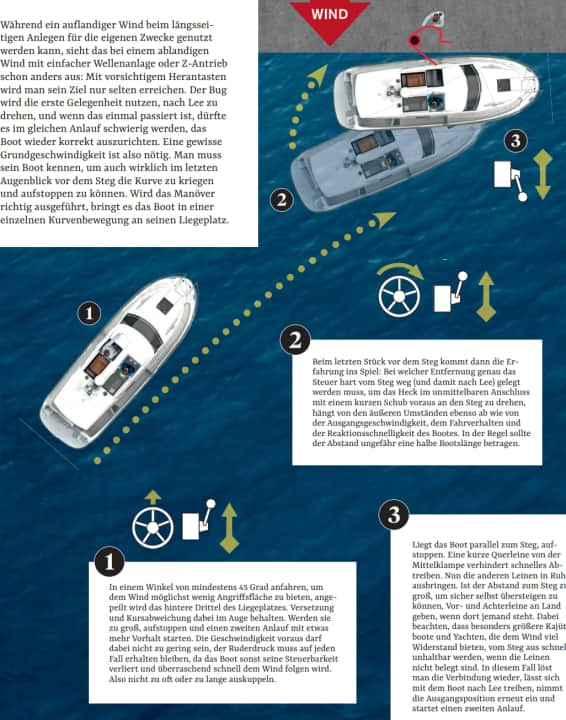

Offshore wind: take off and land with one machine

While an onshore wind can be utilised for your own purposes when mooring alongside, the situation is different with an offshore wind with a simple wave system or Z-drive: You will rarely reach your destination with a cautious approach. The bow will take the first opportunity to turn to leeward, and once this has happened, it will be difficult to get the boat back on course in the same attempt. A certain basic speed is therefore necessary. You need to know your boat to be able to turn and stop at the last moment before the jetty. If the manoeuvre is executed correctly, it will bring the boat to its berth in a single turning movement.

Step 1

Approach at an angle of at least 45 degrees to minimise the wind, aiming for the rear third of the berth. Keep an eye on displacement and course deviation. If they become too large, stop and start a second run with a little more lead. The speed ahead must not be too low and the rudder pressure must be maintained at all times, otherwise the boat will lose its manoeuvrability and follow the wind surprisingly quickly. So do not disengage the clutch too often or for too long.

Step 2

Experience then comes into play for the last stretch before the jetty: the exact distance at which the helm must be turned hard away from the jetty (and thus to leeward) in order to turn the stern immediately afterwards with a short push ahead to the jetty depends on the external circumstances as well as on the initial speed, the sailing behaviour and the reaction speed of the boat. As a rule, the distance should be approximately half a boat length.

Step 3

If the boat is parallel to the jetty, stop. A short transverse line from the centre cleat prevents rapid drifting. Now take your time deploying the other lines. If the distance to the jetty is too great for you to be able to cross safely yourself, pass the fore and aft lines ashore if someone is standing there. Note that larger cabin cruisers and yachts in particular, which offer a lot of resistance to the wind, quickly become untenable from the jetty if the lines are not secured. In this case, release the connection again, let the boat drift to leeward, take up the starting position again and make a second attempt.

Sideways wind

Sideways to the berth? This not only works in onshore winds, but also when the wind and/or current are parallel to the jetty. The boat speed is adjusted so that the speed ahead and the displacement astern cancel each other out, i.e. a standing bearing ashore is created. This requires some practice with the throttle, but has the advantage that even comparatively small gaps can be utilised.

Move sideways

Step 1

The approach is made at a distance of about one to two boat lengths from the jetty. If the boat is level with the berth, reduce the speed ahead so far that it only compensates for the displacement aft and the boat practically comes to a standstill over the ground (although of course it is still travelling through the water).

Step 2

Now all you need to do is turn the helm slightly towards the jetty. The boat will now move slowly in this direction. However, before the bow gets too far round, correct it slightly in the other direction. Once the boat has reached the jetty with its lateral drift, hand over the fore and aft lines. Only then disengage and switch off the engine.