Seamanship: Everything you need to know about anchoring - what to look out for and how to do it right

Christian Tiedt

· 24.08.2025

There's no question that lively harbours have their advantages: electricity at the jetty, restaurants and pubs right next door, proper shower cubicles in the marina. But that doesn't always have to be the case, does it? Fortunately, anchoring offers a tempting alternative, whether in or out of the harbour. Simply "hook overboard" and you might even have your perfect bay all to yourself, complete with the most beautiful natural surroundings.

And peace and quiet. So much for the theory. The prerequisite for this is that the "iron" holds - and the elements must also be taken into account: What are the weather, wind and current doing, and could the current conditions possibly change? With so much necessary seamanship, it is understandable that some skippers prefer the safe box at the end of the day. Anchoring is also just a matter of practice; routine and safety come naturally over time. We have therefore summarised below what you need to know and what you need to bear in mind - for beginners and experts alike.

Anchor types

There is a wide range to choose from: the right type of anchor usually depends on the prevailing anchorage ground in the local area. Plough and plate anchors and their sub-forms are well suited to the sandy and clay soils of coastal and inland waters that are common in this country, as they dig in under tension. They are particularly widespread in pleasure craft.

However, there are also real "specialists" for soft mud or sharp rocks. However, the storage space on board can also be a decisive factor in the decision: some models can be folded flat and stored to save space. For small boats, the folding jib is therefore also the preferred option. The material used is usually galvanised steel, but aluminium or (significantly more expensive) stainless steel are also used less frequently.

Anchor types to click through:

Anchor reasons

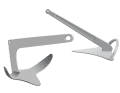

Anchor weight

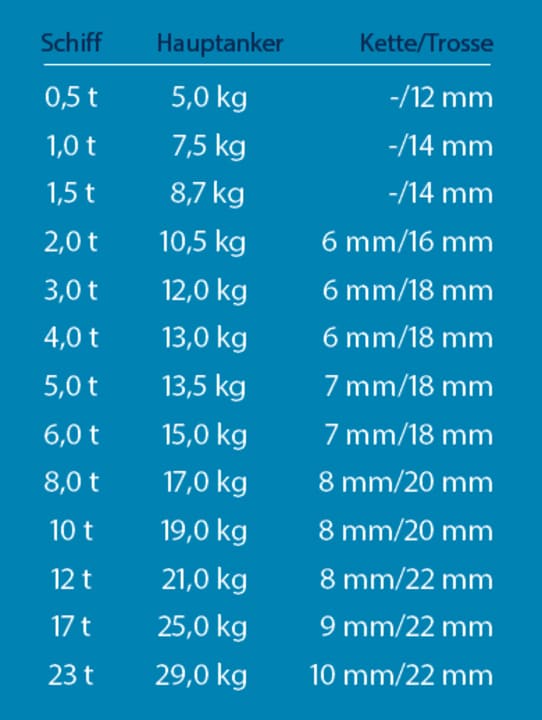

Anchor winches

While anchors on small boats up to around 8 metres in length can easily be deployed by hand and also retrieved by hand, this can easily become a sweaty (and dirty) affair with the heavy anchor of a larger boat. An anchor winch provides a remedy, either in a purely mechanical version for manual operation or with an energy-saving electric motor.

At the touch of a button, all the crockery is gradually brought on deck and disappears into the anchor locker. If necessary, the process is simply interrupted, for example to wash off silt or clay outboard with a hose or bailer. Depending on how the foredeck looks, a horizontal winch (with integrated motor) or a vertical winch can be installed on deck. The motor and gearbox are located inside the boat.

Anchor harness

A good iron alone is not enough; the rest of the anchoring gear must also be adapted to the boat in question and be in good condition. Only then can you rely on it if things get a little "choppy". Viewed from the bow, the anchor gear starts in the chain locker in the foredeck, which even small day cruisers already have. Even if it is often used to stow fenders or similar items, it only really has a place for the chain or line (which must be able to run out freely) - and possibly the anchor itself, if it fits. Otherwise, its place is on the bracket at the bow or (on larger boats and yachts) in the hawsehole in the hull.

Back to the anchor locker: Many a chain and anchor have completely swung out and gone deep because they were not secured. There is usually a bolt in the anchor locker to which the end of the chain or line is attached.

There are three options for the actual anchor harness: pure chain, anchor line with chain leader (there are several metres of chain between the anchor and the line) or pure anchor line. The rule is that more chain on the bottom also means more weight, which keeps a larger boat better in position. Of course, the same kilos must then also be dragged on board during the journey. For smaller cabin cruisers and open sports boats, the options with a line are therefore more suitable.

When it comes to the type of chain, you can choose between galvanised steel and stainless steel. Although the latter is significantly more expensive, it runs more smoothly and is more durable. When choosing a line, make sure that it is a special anchor or lead line that sinks and does not float (as it can quickly end up in the propeller).

In order to keep the anchor's angle of pull as flat as possible and to dampen the pull into the chain in the event of swell, a riding weight can also be deployed on a safety line and hooked into the chain. A buoy connected to the anchor with a trip line not only indicates its position (which helps to determine the swell circle), but can also facilitate recovery.

Anchor watch

When the iron lies quietly at the bottom, the cosy part of the day can begin. But to avoid any nasty surprises, three things should not be forgotten. Firstly, if you need to cool off, make sure you know how to get back on board before jumping into the water - especially if the boat does not have a bathing platform. Secondly, as all kinds of situations can occur at anchor that require a quick response, at least one person on board should (or should be able to) intervene at all times. Thirdly, an anchor watch to ensure that your boat remains in position is actually an integral part of good seamanship.

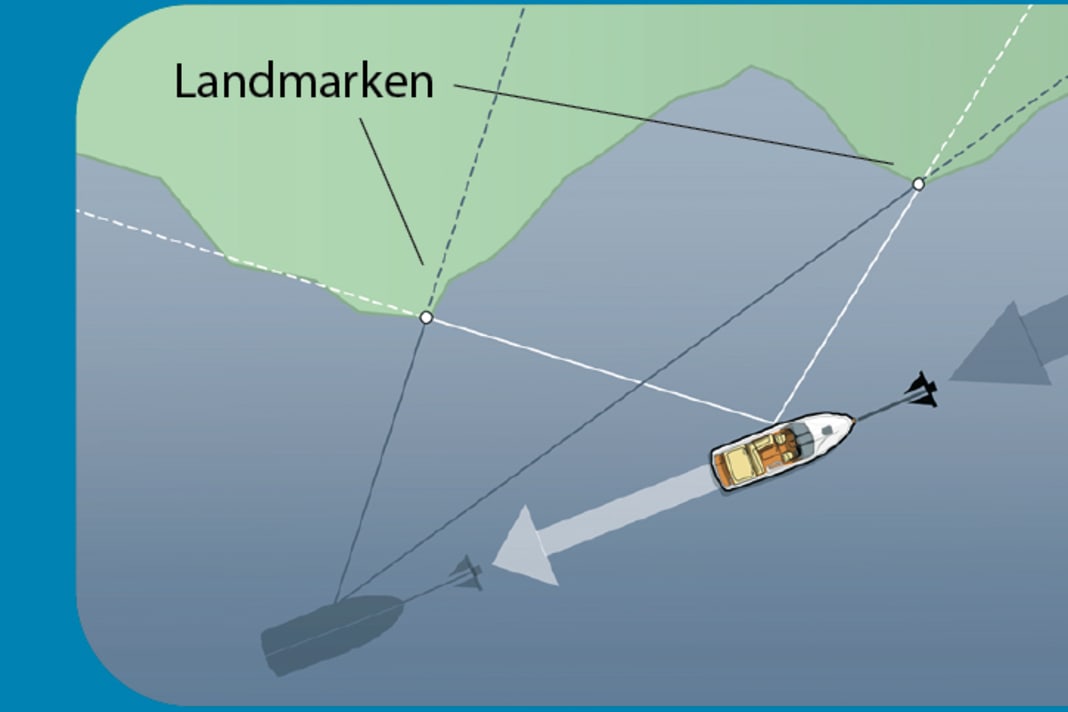

However, whether the watch also has to be kept at night depends on the respective conditions and especially on the weather. On a calm summer night, the situation is certainly much more relaxed than in changeable, stormy conditions. A device with a GPS anchor alarm can serve as a "helper" here, which is triggered when the boat leaves the predetermined area of its swing circle. Otherwise, the good old cross bearing helps to check the anchor position.

Anchorages

The search for the perfect place to drop anchor always starts with a look at the water chart, regardless of whether you are travelling inland or off the coast. Because as cosy as a bay may appear from on board, the decisive factor is what it looks like under the surface. The chart contains this information, from water depth to possible obstacles, and marks areas or sections where anchoring is not recommended or even officially prohibited. The illustration gives an impression of what this information looks like on recreational boating charts for sea waters. However, it looks similar on most inland waterway charts.

It is also helpful to consult the cruising or area guide, as the authors usually describe their personal experiences with the individual anchorages and tell you what to look out for or be prepared for - for example, how popular a bay is or what effect the swell from the nearby ferry dock has. You also need to bear in mind the influence of the elements: How do the wind and current behave at the desired anchorage? The wind should of course always blow offshore, especially if it is strong. If there is a persistent northerly wind, for example, a bay open only to the south would be a good choice, but the wind can shift. If you are surprised by this, you will have to move out of the way to avoid hitting a lee shore - this is the name given to the dangerous situation when, in the worst case, your boat is caught between the onshore wind and the nearby coast. The current weather forecast is therefore an absolute must. Current direction and water depth can also change, especially in tidal areas.

When you arrive at the anchorage, you should first get a general overview. Is there enough room? The swinging circles of all moorings must be taken into account. Another important point may be whether you can land well with the dinghy, if the plan provides for this.

If the map does not provide any further information about the nature of the bottom, you do not have to expect jagged, bare rocks, but obstructive vegetation is still possible. Depending on how clear the water is, "clean" areas appear light-coloured when viewed from above, while overgrown areas tend to be darker. If the water is cloudy - as is usually the case in our latitudes - it is worth a try. If the anchor is not holding, you should bring it up far enough to be able to check it. If there is "lettuce" hanging in the flukes, another spot may be better.

Salvage and breakout with an anchor

If the anchor is to be recovered, the harness is pulled in (by hand or winch) until it is perpendicular to the bottom. The anchor is then brought up. When it comes to the surface at the latest, it will become clear what "condition" it is in. Particularly if the bottom is clayey, the deck hose must be taken to hand and the iron cleaned properly before it can be taken on board and stowed away.

If the anchor does not come out of the bottom easily, it is either buried very deep or has become caught in an obstacle. One option is to "break out" the anchor: To do this, you must engage the clutch ahead and accelerate briefly if necessary. Be careful with the taut chain on the bow! If you don't succeed, you need to use your instincts. If you have deployed an anchor buoy, you can try to recover the anchor directly with the trip line. As the line is attached to the base of the shaft and not to its end, you have a different pulling point and the flukes are pulled forwards under the obstacle.

You can also make do with a line sling, which is guided up to the anchor on the harness and also grips the bottom of the shaft so that the anchor can be recovered upside down.

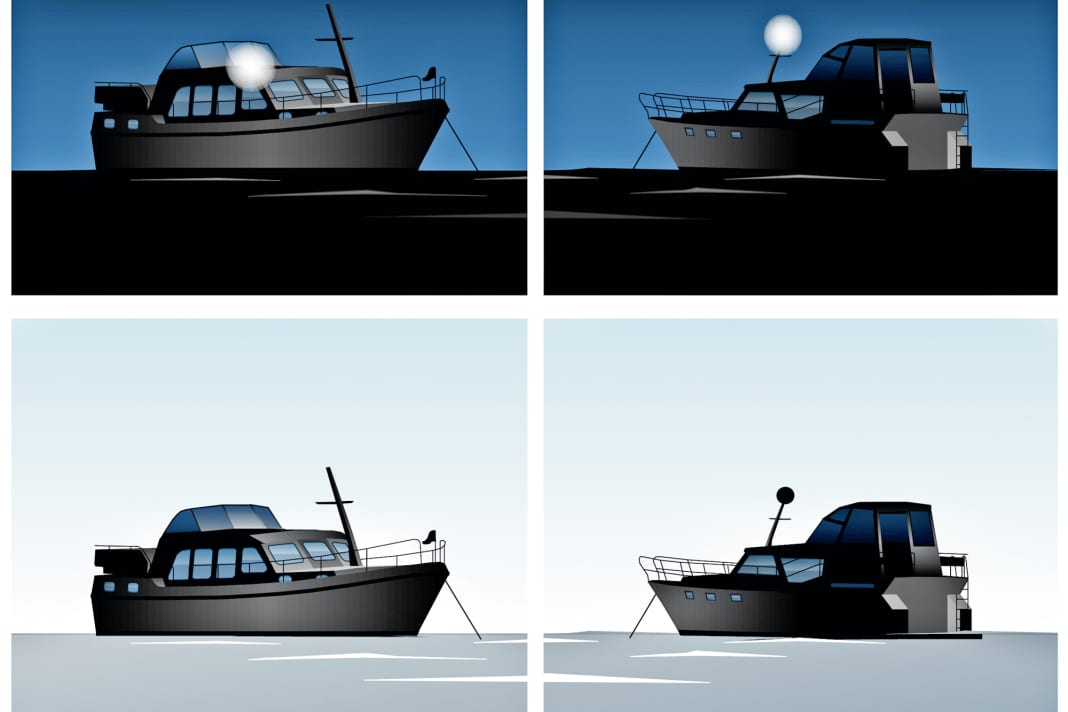

Anchor signals

Moorings must be clearly recognisable to other vessels: On inland waterways, a white, all-round visible light must therefore be displayed on the fairway side at night. At sea, a white all-round light is also required for vessels under 50 metres in length, but where it can be seen best: As a rule, it sits at the highest point, for example on the equipment carrier or in the masthead. During the day, on the other hand, the black anchor ball is mandatory in sea areas, naturally also clearly visible at the front of the ship. Inland, on the other hand, there is no need for a special signalling device during the day.

Anchoring in an emergency

Even if you rarely come to anchor, there is a good reason to always have the iron and harness ready for use - because when the going gets tough, it can be the last resort. This is especially true if the engine or steering system fails in critical situations, for example if the unmanoeuvrable boat is in danger of drifting into a fairway or onto the coast.

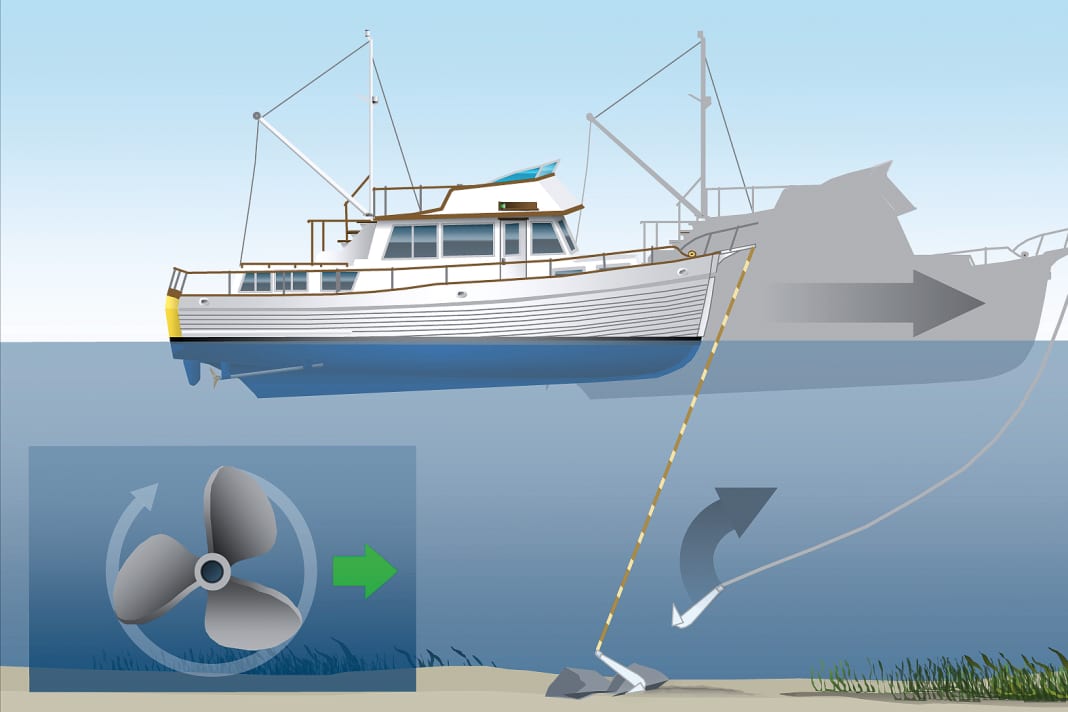

Manoeuvre with the anchor

Once you have found a suitable spot, it's time for the actual anchoring manoeuvre. Discuss the individual steps with the crew beforehand to ensure that communication between the foredeck and the helm position works.

When the anchor is ready to drop, move slowly against the wind or current (whichever has the greater influence on your boat) and stop above the desired position. Now slowly lower the anchor until it has reached the bottom. With a hand-held line, you can feel the grounding, with the winch you have to estimate. The depth of the water is revealed by the chart or echo sounder, the length of chain you have set out can be indicated by coloured markings.

Now let the boat drift astern or help it slightly with the engine. At the same speed, the chain is now evenly extended so that it runs as straight and evenly as possible over the bottom and does not build any "towers". Once the required remaining length is at the bottom (four times the water depth for pure chain, six times for line with chain lead, ten times for line), the chain is secured. Now engage the clutch aft and, if necessary, accelerate a little in a controlled manner so that the anchor can turn into the correct position and slowly dig in. Once this has happened, the anchor harness will tighten and the boat - depending on the forces used - will more or less noticeably "jerk" into the chain and come to a halt.

The chain itself can be used to check whether the anchor is really tight: With little wind or current, as soon as the boat has come to rest, it should lead almost vertically and loosely into the depths. If it is taut, trembling and leading at an angle, this is a bad sign. If the anchor is dragging even if the harness is long enough, you should retrieve it and try again. The bottom may not be suitable after all, so that the anchor cannot take hold. In this case, you should check the nautical chart again and try another spot nearby.

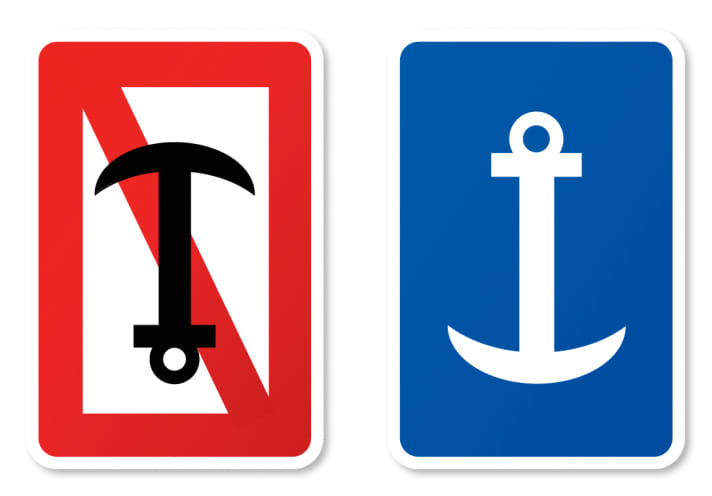

Anchorage prohibitions

The hook is not allowed overboard everywhere: on inland waterways, for example, this applies 50 metres upstream and downstream of the corresponding sign, as well as on canals, lock canals or on sections where anchoring is generally prohibited. Exceptions are then indicated by the second sign, which then only applies on the shore side with the sign. Only the prohibition sign exists in the area of the maritime waterways regulations, where the anchoring ban applies on both sides for 300 metres.

Buten und binnen also prohibits anchoring in narrow and unclear places and in the area of ferry routes and bridges - and of course not in the navigation channel either.