In this article:

Laminating, filling, gluing or priming - epoxy resin is suitable for almost any work on the boat and is often even the first choice. The material owes this versatility to its structure. The resin consists of a polymer with so-called epoxy groups. These highly reactive carbon-oxygen compounds cross-link with the hardener and produce an extremely stable, densely packed macromolecule that is virtually impossible to dissolve chemically.

Once cured, a thermoset is created, which means that thermal moulding is no longer possible. In contrast to polyester systems, epoxy polymers do not require any solvents to evaporate during curing. Depending on the resin system, solvents may be present to change the consistency, but these react during curing. Together with the compact molecular structure, this ensures the watertightness that is important in boatbuilding. Hydrolysis and the associated osmosis damage are ruled out if processed correctly. The absence of vapours also means that no respiratory protection or ventilation system is generally required during mixing and application.

The advantage is the very good adhesion to wood and almost all other materials

Nevertheless, the material is not completely harmless. Above all, contact with the skin must be avoided, both with regard to the resin and the hardener (see occupational safety). Depending on the manufacturer and formulation, the hardener can also have a strong, pungent odour.

Another advantage, however, is the very good adhesion to wood and almost all other materials, which is why practically all two-component primers are based on epoxy resin and almost everything can be bonded with epoxy. Difficulties only arise when bonding thermoplastics such as ABS and PVC, but there are also specially formulated resin systems for this. If the plastic surface is additionally pre-treated and activated by scarfing, nothing stands in the way of a resilient bond. The universal properties of the epoxy can be further optimised for the respective application. For example, as a low-viscosity laminating resin that impregnates the reinforcing fabric particularly well and has a long processing time, or as specially matched resin-hardener combinations for vacuum infusion processes through to prepreg systems that must be stored in a cool place until processing to prevent them from hardening prematurely.

Another option is viscous adhesive mixtures to bond the hull and deck and to glue highly stressed components such as bulkheads and entire floor assemblies into the boat. The market therefore offers a virtually overwhelming selection of epoxy resins for professional users. In addition, there are so-called bio-epoxies such as the Entropy series from West System or Greenpoxy from Sicomin, in which some of the carbon compounds usually obtained from crude oil are extracted from linseed or waste products from biofuel production. Currently, around 30 to 40 per cent of the resin-hardener system can be produced without fossil raw materials. The bio-resins are technically on a par with the best standard products, but cost around 15 per cent more.

Private users are best served by universal systems such as the 105 series from West System

They are, so to speak, the basic chemistry kit for boat builders and can be adapted to the working conditions by selecting the hardener. The ambient temperature and the desired processing time are the key factors here.

If structural bonds or reinforcements are to be produced, fillers and glass fibre come into play, as the strength of the resin alone is not sufficient. Epoxy is not very picky when it comes to reinforcing fibres. Depending on the desired properties, the resin can be processed with glass, aramid or carbon fibres. However, materials that currently appear more exotic, such as flax or basalt, can also be combined well with epoxy. In contrast, the classic standard mat from polyester accessories is unsuitable. It consists of relatively short glass fibre sections that lie on top of each other in a disorderly manner. To prevent the approximately 6.5 centimetre long glass filaments from falling apart when dry, they are glued together with a so-called binder. As long as you are working with polyester, this is not a problem because the binder is dissolved by the styrene and the resin can enclose the fibres. With epoxy, the binder does not dissolve, which is why the resin cannot soak the mat properly and no strong bond is created. Epoxy should therefore always be combined with fabrics or scrims. In the latter case, the fibre strands are held together by warp threads so that no chemical binder is required.

Coating wood is visually appealing and creates an extremely robust surface

The resin serves as a primer. This has several advantages: Firstly, the wood is very effectively protected from moisture and scratches, and secondly, once the resin has hardened, it no longer shrinks, so the primer does not sag even after years and the surface remains even.

When working with the wet-on-stick method, the complete primer build-up can be completed in just one day. Working wet on sticky means that the next layer is applied as soon as the substrate has hardened to such an extent that the finger test still leaves an impression, but no more material sticks to the glove. In this state, the layers chemically bond together, creating the best possible molecular bond without the need for intermediate sanding. Incidentally, this method works just as well for laminating as it does for gluing.

As a comparatively thick layer is applied when priming with epoxy resin, a beautiful depth effect is created with subsequent clear lacquering. Sealing with a two-component lacquer is absolutely essential here, as the only weak point of epoxy resin is its low UV resistance. Without the lacquer coating, the epoxy coating would turn a strong yellow colour after just a few years in the sun.

Basics of epoxy processing 1

Mixing ratio

In contrast to polyester, where the hardener is actually a starter, the two components combine with each other in epoxy systems. The mixing ratio must therefore be adhered to exactly. Otherwise, the material will not achieve the desired properties or will not cure at all. The easiest way to achieve the correct dosage is to use suitable pumps. Important: prime the pumps when using them for the first time - pre-pump with small strokes until resistance is felt. Only then should a full stroke be made. Tip: Always alternate between one stroke of resin and one stroke of hardener, then you won't get mixed up and only have to follow the sequence. Alternatively, resin and hardener can be dosed using a scale or disposable syringes. Caution: The mixing ratios between volume and weight may vary depending on the manufacturer. Values between 5:1 and 10:1 are common, but there are also special cases such as five-minute epoxy with a 1:1 mixture.

Potting and processing time

Curing starts as soon as the hardener is added. The pot life is crucial here. It describes how long the mixture can be processed and ranges from a few minutes to several hours, depending on the system. It is important to note that the time is not determined by the quantity of hardener, but by its properties. As a rule, the specification refers to a temperature of 25 degrees. This is good to know because, as a rule of thumb, the pot life doubles or halves for every ten degrees of temperature change. This must be taken into account when selecting the hardener. As heat is released during curing, the amount of resin also has an influence on the pot life. Large quantities should therefore be mixed in smaller batches and processed from a flat tray so that the heat of reaction is dissipated over a large area.

Mixing

Stir slowly and evenly, also wiping the walls. Stirring quickly will only result in air bubbles. After stirring, decant again and do not use from the mixing cup

Basics of epoxy processing 2

Occupational safety

Epoxy resins hardly evaporate any solvents, so respiratory protection is not absolutely necessary when mixing and working in large rooms. Gloves and overalls are essential, however, as contact with the skin should be avoided. If contamination does occur, do not use solvents! They do more harm to the skin than good. It is better to wash off the fresh resin immediately with soapy water. Tip: Wear two pairs of gloves on top of each other so that the contaminated outer layer can be changed quickly and easily when working. Always wear respiratory protection when sanding epoxy.

Tear-off fabric

The fabric is applied as the final layer when laminating or gluing. It is made of nylon and is impregnated with a release agent so that it does not bond with the resin or laminate. After curing, it can be removed (torn off) relatively easily. It fulfils several tasks. Excess resin is absorbed by the fabric. It also ensures an even laminate surface. The dreaded amine redness also disappears when it is torn off. Cleaning is not necessary; work can continue immediately without intermediate sanding.

Amine blush

During the curing of epoxy resins, a waxy layer can form on the surface. This is a reaction residue of the hardener, which occurs primarily at high humidity and low ambient temperatures. Depending on the hardener and climate, the appearance can range from almost invisible to a dull and greasy surface. Amine reddening becomes a problem during further processing. When sanding, the paper becomes clogged extremely quickly and practically slips off. Furthermore, the wax layer can severely hinder the adhesion of epoxy resin, lacquers or primers. The formation of the residue can hardly be avoided, especially when working outdoors or indoors. However, there are two ways to get round the problem: Either wash the laminate with lukewarm soapy water and a scouring pad and then dry the surface with paper towels. Or you can use peel ply as the final layer.

Robust coating of wood - step by step:

Bonding with groove for clicking through:

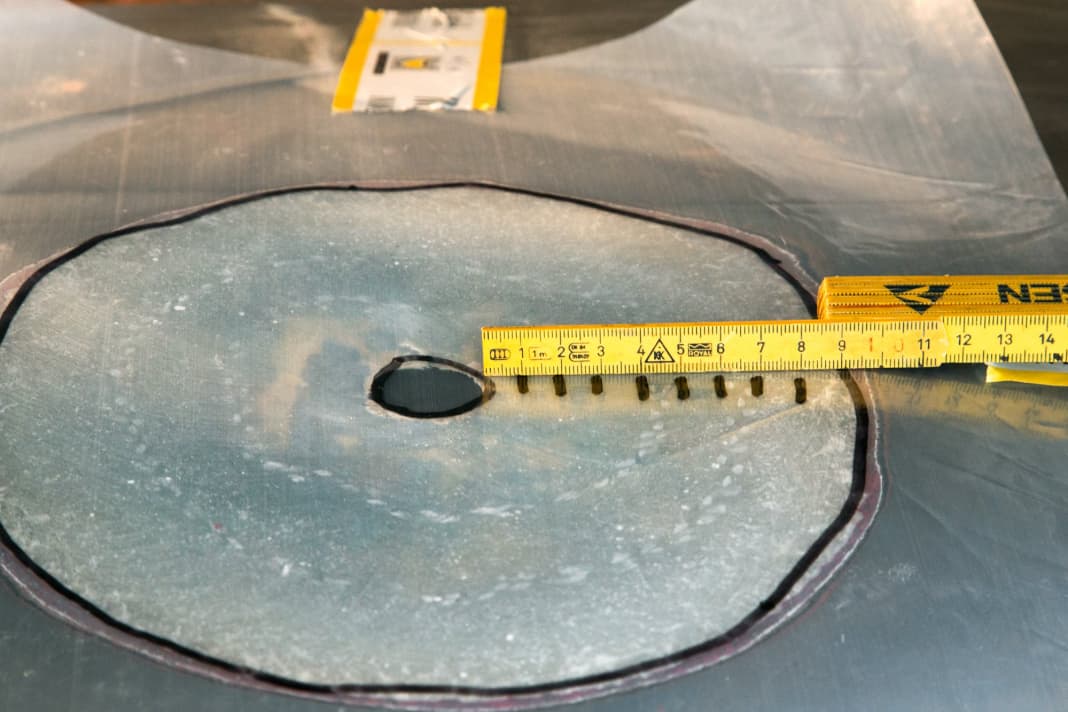

Hole plugging explained: