Boat trim: The 3 most important motorboat types and their trim angle

Fast boats are getting slower, comfort and safety are decreasing, only fuel consumption is showing an upward trend. The cause is always the same: incorrect trim. This includes terms such as trim bolts, power trim, trim tabs, constructive waterline, heel and trim angle. What seems clear and understandable to one person may be a source of despair to another. But proper trimming is not a scientific task. The designer does it on the computer. He places the engine, tank and fittings in the right place and determines the (design) waterline based on the calculated weight. The owner then "only" has to make sure that his boat floats on the pre-drawn line in the water. This means that it should not be overloaded, stern-heavy or bow-heavy.

The trim angle

When motorboat experts talk about the trim angle, they are not talking about a special tool for engine or gearbox repair, but about geometry. This refers to the angle that the longitudinal axis makes to the water surface.

Measure trim angle

The easiest way to do this is with a clinometer, a Heeling meterto its destination. It is important that this is not mounted crosswise, but lengthwise. Also Pendulummounted in front of a scale, or a float (spirit level principle) show quickly and clearly how the trim is.

There is another possibility that many of us always carry with us. This is the Smartphonewhich, with the corresponding app, acts as a kind of spirit level and even displays the corresponding angle.

Effect of different trim angles

Displacer

Key fuselage features

Displacement hulls often have a moderate draught and rounded hull shapes. Instead of gliding over the water, they move through the water and displace it in the process. The keel ensures a smoother and more manoeuvrable ride.

speed

Displacement hulls can never planing and are limited to the hull speed. Regardless of the engine power used, the boat can never exceed this speed. The hull speed depends on the length of the boat's waterline. The longer the hull of the boat, the higher the hull speed can be.

Calculate speed

We have a special Speed calculator programmed for the three main types of displacer, glider and semi-glider. Simply enter the values and be amazed!

Driving behaviour

Displacement hulls are known for their stability and seaworthiness. The hull shape seems to be the key to the relatively easy ride against the waves.

Fuel consumption

At its hull speed, a displacement hull requires around 95 to 100 per cent of its engine load. It is very efficient at a constant, slow speed, but loses this efficiency if an attempt is made to exceed the hull speed.

Trimming of displacers

Displacers must lie horizontally on the water at rest, with the underwater side of the water pass or the upper edge of the underwater coating clearly visible. If either is below the waterline, the boat is overloaded. Lightening is the order of the day.

In contrast to low nose weight (up to 1°), which is perfectly acceptable with a sufficiently powerful engine (usually lifts the bow slightly), something must always be done about stern weight. This increases drag and therefore fuel consumption enormously. The trim angle should not be greater than four degrees for displacement boats. It is often sufficient to stow equipment and provisions from aft to forward. This weight shift can also help to prevent unwanted heeling.

Advantages and disadvantages of displacers

Reliable in rough water

Good fuel efficiency at cruising speed

Limited to torso speed

Typical rolling at anchorages

Glider

Key fuselage features

A glider is lifted by hydrodynamic buoyancy and floats on the water, allowing it to reach high speeds. At low speeds, they tend to yaw (the bow swings back and forth on its own).

speed

Gliders are extremely fast and manoeuvrable. Depending on the engine power and design, they can reach speeds far in excess of the fuselage speed.

Driving behaviour

Instead of travelling "through the water", gliders move over the water surface and are therefore more exposed to the condition of the water surface, i.e. waves.

Fuel consumption

At low speeds, the glider also requires very little fuel. Fuel consumption increases significantly in the transition range from displacement to planing speed. At planing speed, the fuel consumption in litres per nautical mile is reduced again and you are travelling economically.

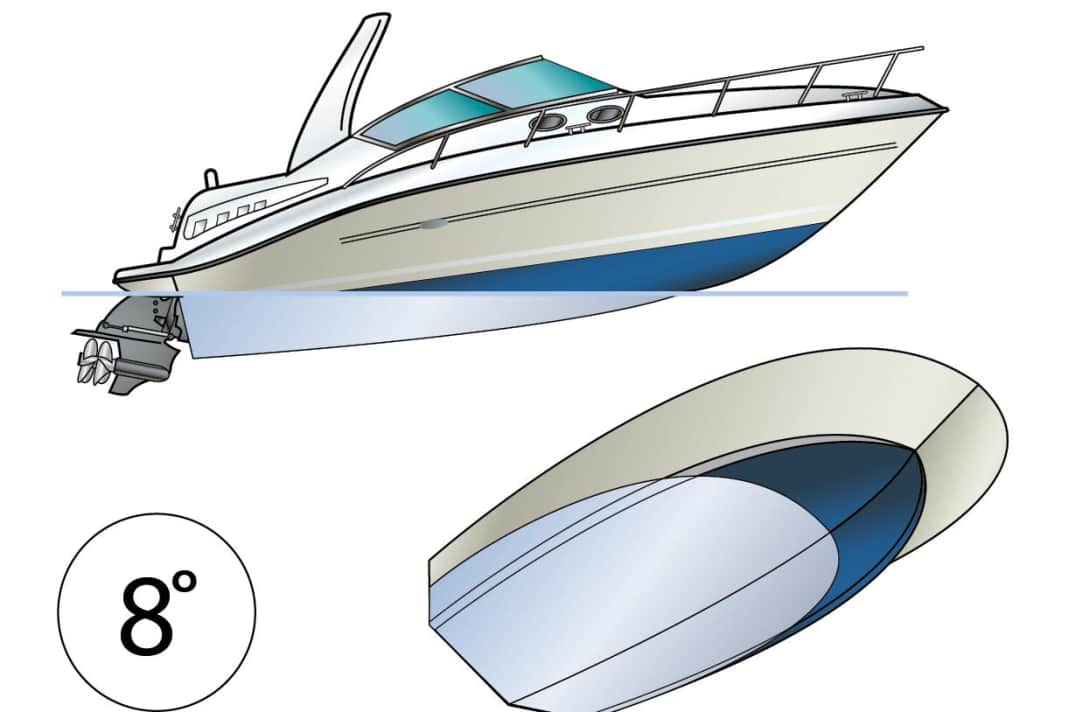

Trimming of gliders

If the hull shape and motorisation are right, gliders overcome their own bow wave and glide on the surface of the water. The trim at rest and at displacement speed is actually of secondary importance for them. There are quite a few gliders that suffer from stern-heaviness when moored and at displacement speed. This is usually due to heavy engines that have to be mounted in or at the stern. Fast day and sports cruisers are 90 per cent powered by outboards or built-in engines with sterndrives; shaft systems with reversing gear or pod drives are used, with a few exceptions, in fast boats from around ten metres. In addition to engine power and propeller tuning, the weight distribution on board must also be right so that the boat can easily switch from displacement to planing at any time when accelerating. Fast gliders sail best and most safely with trim angles between two and four degrees.

Advantages and disadvantages of gliders

High speeds possible

Excellent manoeuvrability

Uncomfortable fast ride in rough water

High fuel consumption during the transition to gliding

Semi-glider

Key fuselage features

A semi-planing hull combines features of the displacement hull and the planing hull. It displaces water at low speeds, but can generate a certain dynamic lift at high cruising speeds, making it faster.

speed

The speed of semi-planing hulls lies between that of displacers and planing hulls. They can reach higher speeds than pure displacers without achieving the full glide of a glider.

Driving behaviour

Semi-gliders are often heavier than pure gliders and travel at slow speeds like a displacer. If you step on the throttle and sail in the half-glider range, they are usually stable on course but with a raised bow.

Fuel consumption

At low speeds, the semi-glider generally consumes little fuel, which increases noticeably at high speeds.

Trim of semi-gliders

The compromise between displacer and glider places special demands on trimming. Half-glider fuselages are particularly sensitive to weight distribution and trim. Half-gliders should also not stretch their nose (bow) too far up into the sky if possible. Trim angles over six degrees fall into the category of "uneconomical".

Advantages and disadvantages of semi-gliders

Combination of speed and comfort

Flexibility: economical at low speed, fast when needed

Requires a more powerful motor than a displacer of the same length

Less comfortable than gliders at very high speeds

More articles on the subject of boat trim:

- The 3 most important motorboat types and their trim angle

- To adjust the trim bolt

- How to achieve the power trim

- How the power trim works in practice

- Trim tab systems and the advantages they offer

Lars Bolle

Chief Editor Digital