A text by Christoph Schaefer

The harbours in the Mediterranean are full to bursting. It is becoming increasingly difficult for captains to find suitable berths. Owners are complaining about rising costs.

The anchorages are overcrowded and it's often like a campsite: people know each other, say hello, see what their neighbour has, what they're up to and try to outdo them. This naturally raises the question as to why there are so few yachts sailing around the world beyond these glamour ghettos.

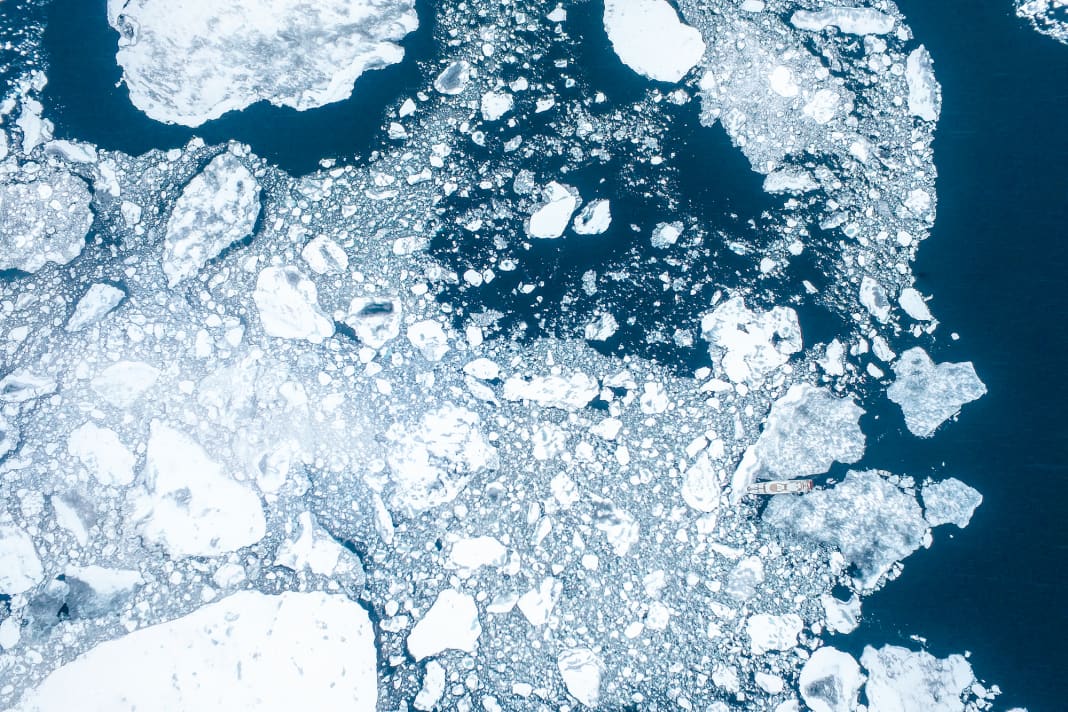

In yacht magazines, shipyards and brokers advertise with pictures of exotic regions; time and again we see explorers in the ice - but often only photomontages. The longing for adventure and secluded beaches is clearly an important marketing tool for our industry. And indeed, adventurous owners are drawn out into the wide world.

During a trip to the Caribbean in spring 2015, the owner approached me about the possibility of sailing to the Norwegian fjords on the condition that I would be back in the Mediterranean on 1 July. Although I had spent most of my time as a captain in the tropics, I felt that Norway was a dream destination that I really wanted to experience.

A journey into the unknown

However, the weather in the North Atlantic can be quite rough, and the prospect of travelling over 7500 miles under great time pressure to cruise through the fjords in Norway for a week was anything but appealing. I suggested Greenland as an alternative destination. For one thing, the route along the east coast of America offers a harbour of refuge every few hundred miles, and the longest passage is only 800 miles from St. Johns/Newfoundland to the coast of Greenland. On the other hand, Greenland offers a completely new experience: in addition to fjords and unspoilt nature - ice. In the search for Greenland activities, one of the options was heli-skiing, which was still possible in June and provided the decisive impetus to actually carry out this trip. This first trip to the Arctic Ocean was a journey into the unknown for me.

Although I had prepared myself as best I could, I was well aware that I had very limited experience in ice. My biggest concern apart from icebergs was the icing of the superstructure in strong winds and temperatures below freezing. This icing has a negative effect on stability. The weather forecast when we left St Johns was not good at all, but at least it promised temperatures above freezing.

A low-pressure system with wind force 8 to 9 threatened to catch up with us. Weather forecasts are difficult in this area, low pressure systems build up quickly, merge into a perfect storm or collapse again. Ice fields are strongly influenced by the wind and surface currents. In general, the southern fjords of Greenland are full of pack ice in spring and are not navigable. The pack ice drifts from north to south along the east coast of Greenland. On 31 May, we were fortunate to find open drift ice with icebergs and ice floes smaller than 100 metres in the south of Greenland.

Our destination was the capital Nuuk, where the owner wanted to board on 7 June. With the low pressure area and the expected wind force 8 to 9, it didn't seem advisable to keep to this date at all costs. Four days later, after a relatively calm crossing, we entered the Arsukfjord to wait for better weather. As predicted, we found the Arsukfjord to be ice-free. Only a few minutes after the anchor was set, the wind reached us.

Onward journey to Nuuk with "Kamalaya"

On 4 June, the southwesterly wind had not only driven the ice field around the southern tip of Greenland, but had also thickened the drift ice to an ice cover of 6/10. The weather forecast had already improved significantly by the evening of 5 June. A window opened for the onward journey to Nuuk.

I think it's quite normal for the crew to gather on the bridge on every yacht when embarking and disembarking. However, a new experience north of the Arctic Circle, where we had 24 hours of daylight, was that the crew didn't want to go to bed at all. This was repeated on the Svalbard voyage a year later. Again and again I had to ask the crew to get some rest and go to sleep.

Also interesting:

In Nuuk, we were greeted not only by some colour, but also by deeply relaxed authorities. The berth reservation was made when we entered the harbour. Customs stopped by without any obligation. The police asked me to appear whenever it was convenient for me.

In Nuuk we also met our two ski guides for the first time, Arne and Adam from Greenland Extreme, both experienced skiers. Adam was part of the Olympic team for Greenland, and both are hunters and trappers. Together with the heli pilot, they discussed the plan for the next week. As is often the case, the weather didn't play ball and the owner's arrival was delayed by another 24 hours.

Greenland only has an airfield with a runway suitable for a large jet in Kangerlussuaq. This airfield is located high on the edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet and is usually free of fog. From there, smaller aircraft fly to the few towns along the coast, such as Nuuk, Maniitsoq, Sisimiut and Ilulissat. These coastal towns are often covered in fog, which severely affects air traffic. This should not only cause problems on the day of arrival, but also on the day of departure. Instead of waiting for an improvement in Nuuk, we travelled to Maniitsoq. As the weather forecast predicted, the aircraft was able to land there. From now on, our journey took us steadily northwards.

Back to the Arctic Ocean

The monochrome landscape we had seen so far changed abruptly on day two, when we anchored in the Evighedsfjord. A cloudless blue sky gave us ideal flying weather for heli-skiing. During these days we saw neither another ship nor any people. There was not a vapour trail to be seen in the sky, no noise except the whispering of our generators, all in bright sunshine and temperatures of up to 10 ºC, which motivated our guests to go water biking and swimming - in dry suits. We travelled as far north as Sisimiut, from where the owner and his guests flew home. Unfortunately, we had to cancel our next trip north to Disko Bay as the pack ice was still too thick for "Kamalaya". However, it was clear that we wanted to return to the Arctic Ocean on another trip. In spring 2016, we made our way to Norway.

We had learnt a lot on our trip to Greenland. So this time we were in a much better position. Before we set off from Holland on course for Spitsbergen, we took the precaution of buying a polar bear costume so that we could effectively counter any disappointment on the part of our guests. More important, however, were the tenders. In Greenland the year before, we had only had our two standard tenders on board, a 6.60 metre open boat from the Meyer yacht yard and a 6.40 metre Pascoe Rescue Boat. Longer journeys in these open boats without wind protection had been a torture before Greenland.

This time we towed our Wajer Osprey 38' from Holland to Svalbard and back to the Mediterranean. In addition to the wind-protected cockpit, the Wajer also has a heating system, which made a significant contribution to comfort. Another bonus was that the bow wave pushed ice to one side, clearing a path for the Pascoe Rescue Boat. We needed this to land our guests on the shore. In future, I would even take a small inflatable boat with an outboard motor with me to make landing manoeuvres easier, especially in swell. A large, heavy tender can be a problem in adverse conditions.

Home to 3000 polar bears

And then we headed for Svalbard, as Spitsbergen is now called in Norwegian. Svalbard is home to around 3000 polar bears. We wanted to find them. At least that was our goal.

This time we hired Jason Roberts as our guide. Jason is the man behind the camera for much of the polar bear and penguin footage for the BBC series Planet Earth and Blue Planet, Frozen World and The Hunt, for example. There is probably no one better at tracking polar bears in Svalbard than Jason and his team. It was a great pleasure to have Jason as my guide for this Svalbard trip. When I asked him what our chances of actually finding polar bears were, he said that he couldn't guarantee a number, but that we would see some without a doubt. Jason turned out to be right, and we saw polar bears on several days, including a mother with two cubs who had just caught a seal.

Icebreaker clears the way for "Kamalaya"

As "Kamalaya" has no ice class and we wanted to go as far as the pack ice limit, we chartered a small icebreaker, the "Havsel", a 35 metre-long seal catcher under the command of Captain Bjorn, who had been at sea in the Arctic Ocean for 40 years. This not only gave us the opportunity to navigate in ice fields that would no longer have been passable for us under the Polar Code, but we could also draw on the "Havsel" captain's many years of experience.

On "Havsel" we also transported additional equipment that we needed for this trip: ten snowmobiles to search for polar bears on the vast ice fields of Nordaustlandet, the second largest Svalbard island. "Havsel" also took on board rescue equipment that would allow us to survive at least five days off the yacht on the ice. We also completed the drill prescribed by the Polar Code with our guests to practise survival in the ice.

What surprised me on both trips was the fact that the cold played a much smaller role than I had expected. Of course, it was exhausting for the deck crew to wash "Kamalaya" at temperatures around 0 ºC.

Water sports were also limited, but neither the guests nor the crew complained about the cold. Low temperatures are part and parcel of travelling to the Arctic Ocean. One of our biggest problems was getting the jacuzzi up to temperature. The water in the tanks had cooled down to 2 ºC and we had completely underestimated how long it would take to reach a temperature of 38 ºC. Any other worries? One or two flanges in our fresh water system had to be tightened and loosened again when we reached warmer waters. And nobody expected that the ice maker for the drinks on the sun deck would be the only piece of equipment that wouldn't survive the cold: a plastic part in the water pipe crumbled. We fixed the problem with a chainsaw and a block of ice.

Apart from these events, "Kamalaya" did extremely well on both trips. Nevertheless, some colleagues were reproachful: this is how you destroy a paint system. But: "Kamalaya" did not suffer a single scratch to its paintwork!

The charts we used for Greenland and Svalbard were Transas TX-97 and MaxSea with Jeppsen alongside charts from the Danish and Norwegian Hydrographic Institute. I was impressed by their accuracy. And climate change? The retreat of the glaciers is enormous. Extreme caution is required when leaving the mapped lake areas. In any case, it is advisable to have a forward-looking sonar on board or, what I personally prefer, a WASSP, a Wide Angle Sonar Seafloor Profiler, a multibeam depth gauge that is installed on the tender and transmits the data directly to the bridge of the mother ship via a wireless link.

And the communication?

The last few years have seen a radical change in communication. Everyone, whether owner, guest or crew, now gets nervous quite quickly when internet access is lost. In the high latitudes, the already vexing issue of VSAT becomes even more difficult. The satellites are so low on the horizon that it is easy to lose sight of the geostationary satellites in the fjords. Iridium satellites In low Earth orbit, the data connections are unfortunately still very slow and almost unusable.

However, this fortunately changed in the same year with the next generation of satellites that were installed in 2018. Iridium is also expected to achieve GMDSS certification, which will make the upgrade to GMDSS A4 much easier for yachts.

"Kamalaya" is ideally positioned for voyages to the Arctic Ocean

Through my work for the SuperyachtGLOBAL team, I have now enabled more owners to experience a polar voyage. Although it has become somewhat more difficult to travel to the polar seas since 1 January 2018, the Polar Code certification for yacht and crew is unproblematic. The experience for the owners, their guests and the crew in the Arctic Ocean is fantastic. Every one of our customers has given us the feedback that this trip was the best they have ever done with their yacht. These are experiences that are simply impossible in the Mediterranean and the Caribbean.

Incidentally, "Kamalaya" was the first Amels LE180 to achieve its Polar Code Certificate of Compliance in January 2018. The crew also has their Polar Code STCW endorsement. "Kamalaya" is now ideally positioned for voyages in the Arctic Ocean.

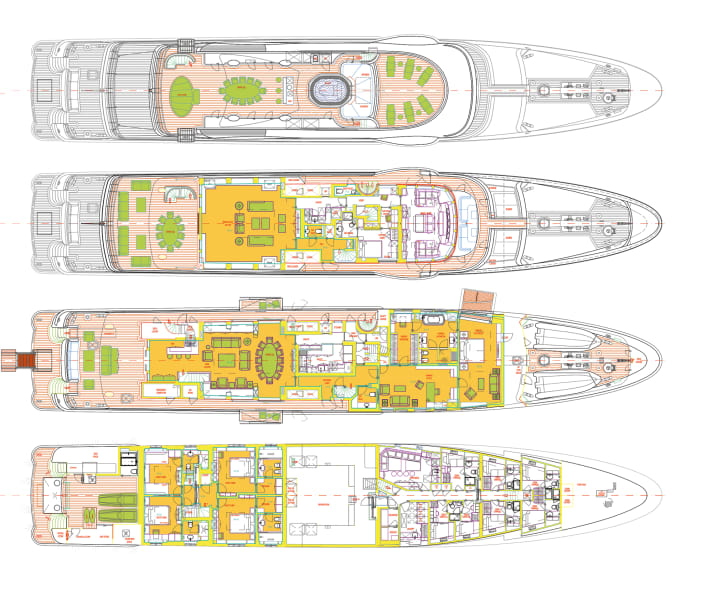

Technical data

- Length over everything: 55,00 m

- LWL: 48,90 m

- Width: 9,00 m

- Draught (100 %): 3,35 m

- Displacement (100 %): 740 t

- Gross tonnage: 671 GT

- Material: Steel, aluminium

- Motor: 2 x MTU 16V 2000 M70

- Engine power: 2 x 1050 kW

- Speed (max.): 15.5 kn

- Speed (travelling): 13 kn

- Fuel: 115 000 l

- Range: 4500 nm @ 13 kn

- Generator: 2 x Northern Lights, 150 kW

- Water: 17 000 l

- Guests: 12

- Crew: 14

- Construction: Amels

- Styling: Tim Heywood

- Interior design: Owner

- Flag: Grand Cayman

- Classification: Polar Code

- Shipyard: Amels, 2013

This article appeared in the 02/2018 issue of BOOTE Exclusiv and has now been revised by the editorial team.