by Sven M. Rutter

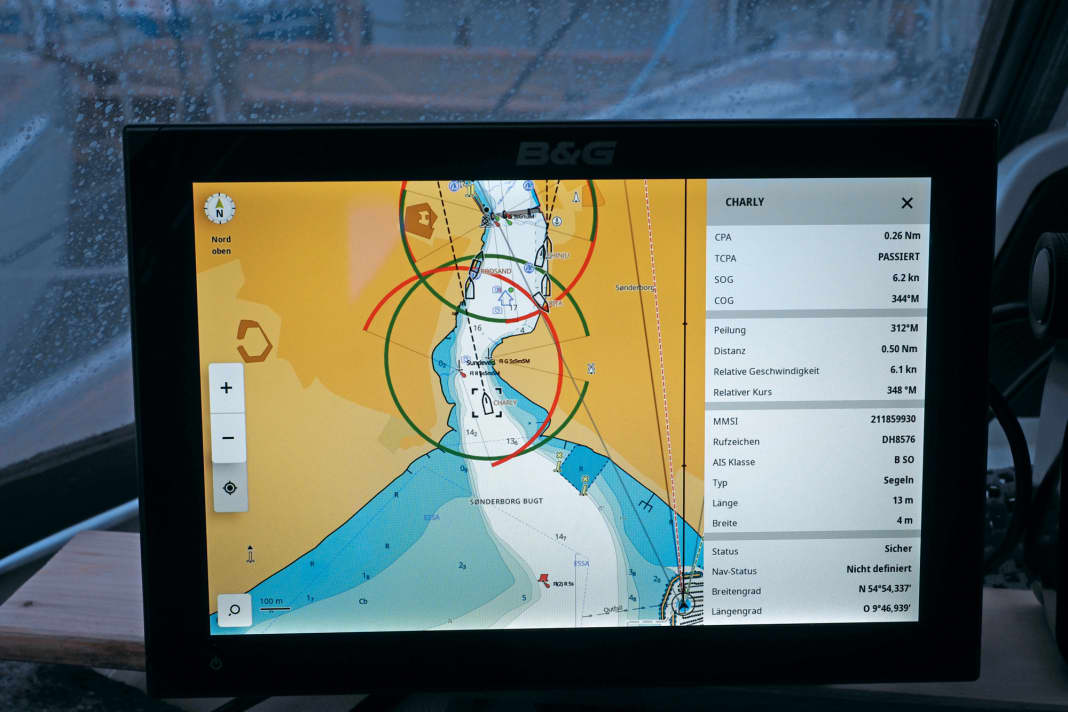

Hardly any other new technical development has spread as quickly in the maritime industry as the automatic identification system, or AIS for short - proof of its practical benefits, which many boaters have now also recognised. It is true that the position and movement of other ships can also be detected by radar, and the expected approach (CPA/TCPA) can also be checked using appropriate evaluation procedures (e.g. MARPA). However, it is not possible to recognise who or what you are dealing with. Not even the type and size of another vehicle can be reliably recognised in the radar, as the size of a radar echo ultimately only provides information about the reflectivity of the radar target. However, there does not necessarily have to be a direct correlation with the actual size of the target - keyword: plastic yacht. Not to mention indications of existing course changes and voyage-related data. In addition, reliable radar image interpretation requires a great deal of experience.

AIS data is cheaper to receive and less of a guessing game

In principle, a pure receiver on board is sufficient for traffic analysis using AIS, although this eliminates a significant advantage - namely, in addition to better "seeing", better "being seen" can also be realised. This advantage in particular can be decisive in critical situations, especially in uncertain weather. Because in order to appear reliably on the radar screen of other ships, even if the sea/rain filter is turned up, a certain amount of effort is required on motorboats. The frequently used radar reflectors in slim tubular form are hardly capable of this, as the latest test report in our sister magazine YACHT (issue 8/22) confirmed.

With an AIS transponder, on the other hand, your own boat is almost certain to find the plotter screens of the big boats. The installation effort is manageable and the devices are significantly cheaper than a radar system. In addition to stand-alone models, combinations of VHF marine radio system and AIS transponder as well as black box versions are available. Which variant is most suitable depends on the conditions on board, the desired equipment and the financial investment.

But first a little theory about the AIS system. The functional principle is as simple as it is impressive: in order to identify each other and, if necessary, contact each other, all active participants regularly exchange their ship data - including ship name, call sign, vehicle type and size - via two VHF maritime radio channels reserved for the system. The MMSI number is also transmitted with each message, which can be used to call the sender directly via marine radio using digital selective calling (DSC) if necessary.

SOTDMA and CSTDMA process

To ensure that the AIS transmissions of the individual ships do not overlap, a sophisticated organisational principle was developed that does not require a moderator.

The Self Organised Time Division Multiple Access, or SOTDMA, method is used for Class A AIS transponders, as prescribed for ships that are required to be equipped. It enables participating vessels to reserve fixed transmission slots for their planned transmissions on the two VHF channels used by the AIS. In simple terms, a joint transmission plan or schedule is drawn up by mutual agreement. However, Class B AIS transponders designed for recreational boating were not initially intended to participate in the SOTDMA procedure. They had to make do with the so-called CSTDMA procedure. The abbreviation CS stands for "Carrier Sense". It means that these devices have to listen until a free slot is found for their transmissions. With very high traffic density, these devices therefore transmit according to opportunity rather than according to plan.

New standard: SOTDMA procedure also permitted for Class B AIS transponders

This prioritised AIS traffic for shipping requiring equipment over recreational shipping, which has several consequences. For example, the message from a CS transponder must fit into a slot, as there is no guarantee that the following slot will also be free. This in turn limits the scope of the information provided. The frequency of transmissions is also strictly limited for CS models. SOTDMA devices provide significantly more frequent updates for dynamic journey data.

Since an amendment to the relevant standard, Class B transponders are now also permitted to participate in the SOTDMA process. At the same time, the standard provides for more frequent updates of the sailing data for fast boats. At first glance, this may seem less relevant for slower touring boats, but with an SO device they also benefit from secure transmission locations and intervals as well as a slightly higher output of five watts. CS devices are only allowed to transmit with two watts. In practice, however, the range depends more on the position of the antennas than on the transmission power.

Integrated antenna switches are not available for all devices, but splitters simplify installation

When selecting a product, you should also consider the installation options in addition to the AIS standard. Especially with regard to suitable antenna locations. Every AIS transponder has a built-in GNSS receiver, for which a corresponding mushroom antenna must be installed on board. Some devices come with an integrated GNSS antenna, but then a location must be found for the transponder where the satellite signal can be received. Not all devices accept feeding in the GPS position via the network, so you should use the solution provided by the manufacturer.

In addition, a VHF antenna must be connected to each AIS transponder. There are basically two options here: the installation of a stand-alone AIS antenna or the use of a so-called splitter, i.e. an active antenna splitter. With the latter, an existing VHF marine radio antenna can also be used for AIS transmission and reception.

Devices with an integrated splitter are generally cheaper than the sum of the individual components and are also easier to wire. Some AIS transponders with an integrated antenna splitter also allow the connection of additional receivers such as radios or televisions.

What an AIS transponder needs on board

In terms of price, stand-alone appliances with their own controls and display mark the upper class. However, they are also ahead in terms of functionality, but require an easily accessible installation location. Black box devices are more frugal in this respect, but are dependent on the capabilities of the analysis software used: If the operating system of the multifunction display or plotter used for AIS evaluation does not support it, it cannot be accessed, which also applies to the corresponding apps.

For some functions, however, external accessories can be used, such as a separate alarm transmitter. Corresponding connection options on the transponder then become a further selection criterion.

More about electronics:

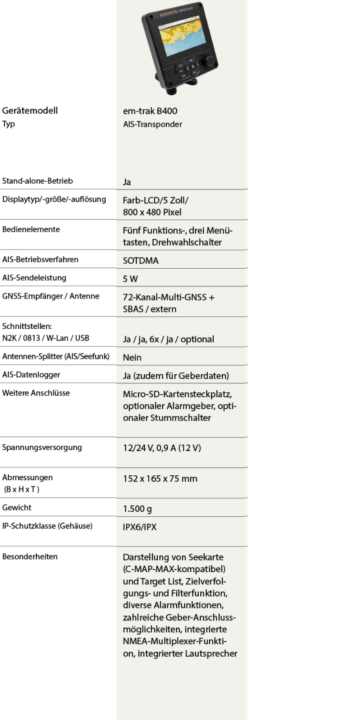

While stand-alone operation is a matter of course for Class A transponders, corresponding recreational marine products are few and far between. We have only found one such device that also supports the newer SO standard: It is the B400 from em-trak. There is also the MA-510TR from Icom, which only supports the CS standard. And then there is the Cortex-Hub from Vesper Marine, which as a combination device also offers the functionality of a VHF marine radio system.

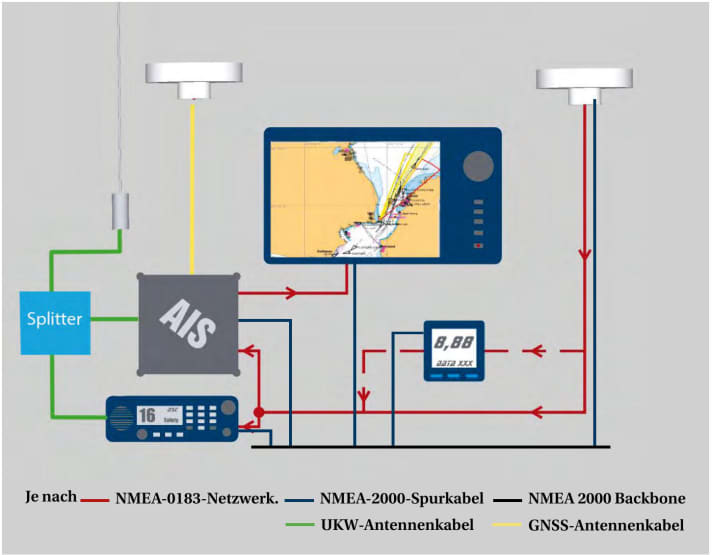

In the simplest case, an AIS transponder only needs power, a VHF radio antenna and programming to be ready for operation. However, if you are transmitting yourself, you usually also want to see the data of other yachts and ships on the plotter. Depending on the device and installation location, an additional GPS antenna may also be required.

On-board electrics: What you need to know about AIS

Owners who are less familiar with on-board electrics may be put off by the sheer number of connections required. However, the whole thing is not rocket science. Especially if the boat is already equipped with an NMEA200 standard network, because then the transponder can simply be coupled to the backbone. The same applies to SeatalkNG or Simnet networks; all you need is a suitable adapter cable, as the connectors are not compatible.

Older NMEA0183 systems are somewhat more complex. As the transponder has a lot to communicate to the plotter, AIS devices use the standardised NMEA data format, but at a speed of 38,400 bits per second (bps) instead of the normal 4800 bps. Devices that understand AIS data can also cope with this higher speed. However, many simple plotters only have one input for NMEA0183. If several data sources are available, things get tight - regardless of the speed.

As a remedy, practically all AIS receivers available today have a data multiplexer. This means that they receive the GPS data on one connection and output it together with the AIS data records on the other. The connected navigation device thus receives data from two sources via one input. In principle, this works regardless of where the data records come from.

It is rarely possible to avoid installing an additional GPS antenna

In practice, however, there are some models that only forward certain data packets from the GPS. This can cause problems if wind and water depth from the instrument system are also to be used on the screen. In this case, an external multiplexer is required.

With transponders, it is rarely possible to avoid installing the additional GPS antenna. Most devices do not work with position data fed in via the network.

The appropriate interfaces must be available for integration into the network on board

In principle, AIS devices can be easily connected to the on-board navigation electronics via a tried-and-tested NMEA0183 connection (in high-speed mode) - networking is primarily relevant for analysing the received data anyway, see box on the left. An NMEA2000 interface (N2K) is particularly interesting if the on-board navigation electronics are already integrated into a corresponding network. The AIS transponder can then be connected to the backbone. However, as with VHF marine radio systems, the power supply for AIS transponders is separate, as the N2K network does not provide the power required for transmission.

With proprietary network standards, it can also pay off to stick with the same manufacturer when choosing a device. Anyone navigating with a smartphone or tablet should look for an integrated WLAN module so that the AIS data can reach the mobile device without additional hardware. In the case of black box devices with WLAN, it is important to ensure that data reception is not impaired by concealed installation. A connection option for an external WiFi antenna can pay off here.

Most transponders come as a black box, the combination with the marine radio system is rare

With black box devices, the frequently available USB port is primarily used to programme the ship data during installation. This is usually done using a laptop and software provided by the manufacturer - but is sometimes also possible using a compatible plotter, a mobile device app or a browser-based tool. With stand-alone devices, programming is carried out directly via the transponder's user interface.

Some devices also have an integrated data logger that continuously records the received AIS information as well as its own GNSS data. Some devices are equipped with a memory card drive for this purpose.

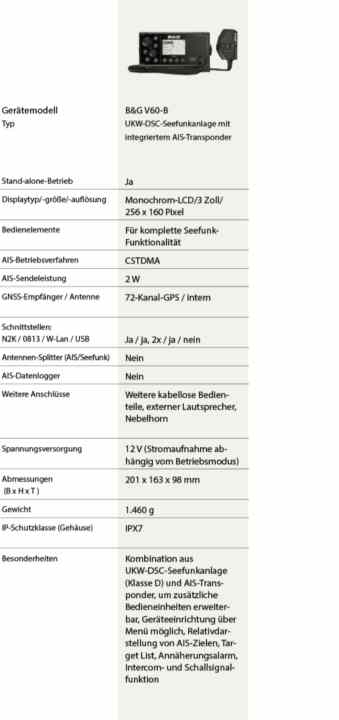

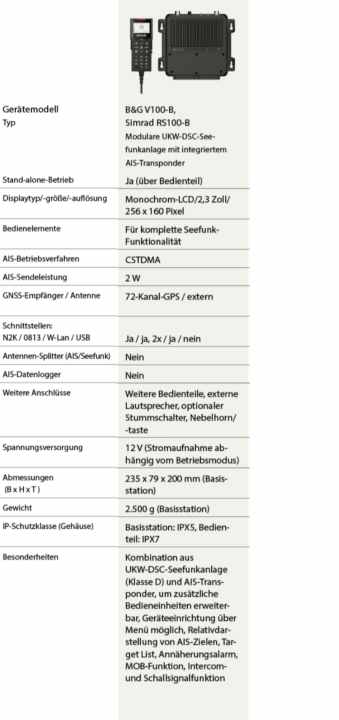

While VHF marine radio systems with integrated AIS receivers are now widely available, combination devices with integrated AIS transponders are still an exception. We only came across three during our research: the Navico B&G V60-B and B&G V100-B devices. The latter is also available as the Simrad RS100-B. There is also the Cortex Hub V1 from Vesper Marine. The Navico devices are available either as a stand-alone version or as a black box with a separate control unit. They are both VHF DSC marine radio systems with an integrated Class B AIS transponder, although they do not have an integrated antenna splitter.

The AIS transponders presented and their special features

The Cortex hub comes with an antenna switch, but is in a league of its own. Smartphone-like control panels with a touchscreen, a wide range of integrated sensors and the apps offered by the manufacturer with various monitoring and control functions, which can also be accessed remotely with an optional mobile phone connection, give the product several unique selling points. The Cortex Hub is available in two versions: under the model designation M1 as a black box AIS transponder, which can be converted into a stand-alone device with an optional control panel, and under the product designation V1 with an additional integrated VHF DSC marine radio system.

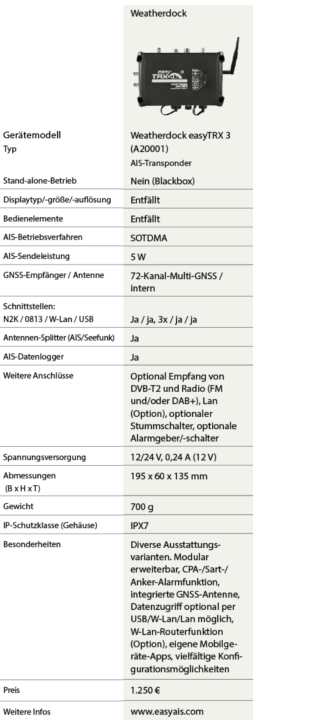

Meanwhile, the easyTRX 3 from Weatherdock, which is available in a wide range of equipment variants to meet all requirements and whose range of functions can even be expanded at a later date, is probably the most versatile device among the SO standard black box solutions.

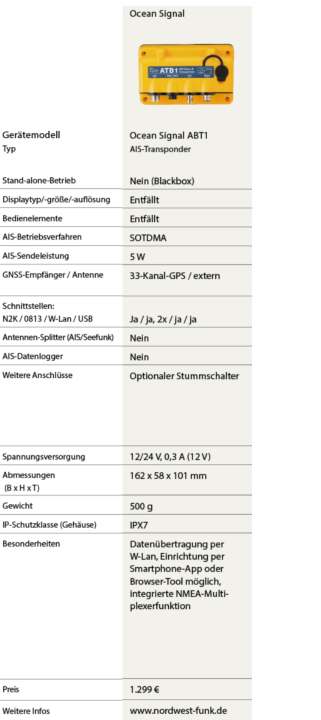

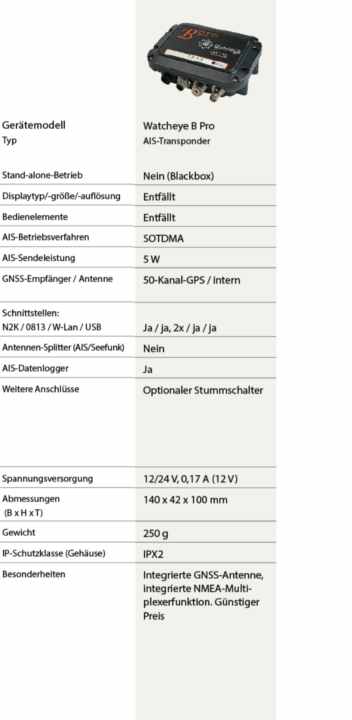

The AIT5000 from Digital Yacht also comes with numerous features and its own apps. Like the aforementioned devices, the ABT1 from Ocean Signal also comes with WiFi, but without a connection option for an external WiFi antenna and without an integrated FM antenna splitter. The same applies to the Watcheye B Pro, which has a very favourable price.

Safety through AIS: Be aware of the limits

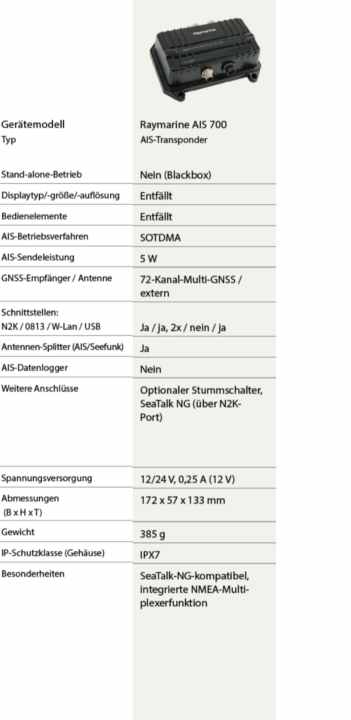

The well-known marine electronics manufacturers Furuno, Garmin and Raymarine also offer compatible black box transponders for their navigation systems in accordance with the SO standard (see table for details). Navico has a successor to the tried and tested NAIS-500, which still works according to "CS", in the pipeline (Simrad V3100). Thrifty customers who are interested in the same operating standard and additional features will find the AdvanSea TR-210 a favourable offer.

More about security:

Whichever solution you choose, in practice you should always be aware of the limitations of the system in addition to all the advantages of AIS. The most important limitation is that with AIS, you can only see those ships that also have a corresponding device and transmit AIS data - and that is by no means all of them. This means that there is always an element of uncertainty, especially when visibility is reduced.

What should you choose - are smartphone apps also an alternative?

AIS is therefore not able to replace the tried and tested radar, but it is an excellent addition. AIS promises additional benefits in MOB situations if the crew is equipped with appropriate AIS emergency transmitters.

Charterers can make do with a mobile solution if the charter yacht is not equipped with AIS. However, only a receiver solution can be considered, as a transponder would first have to be registered by the owner. Weatherdock, for example, offers a compact AIS receiver based on a Raspberry Pi computer. However, AIS smartphone apps that display so-called "live data" from other ships on the Internet do not offer an alternative. On the one hand, there is always the question of whether the positions displayed are up to date. Secondly, this data is recorded by shore stations, meaning that the detection of a vessel depends on its distance to the nearest receiving station and not to the vessel itself.

Market overview: These AIS transponders (class B) are available and what they offer

Stand-alone and combination appliances

Navico B&G V60-B

- Price: 1.367 €

- bandg.com

Navico B&G V100-B

- Price: 1.873 €

- bandg.com

Vesper Marine Cortex M1

em-trak B400

- Price: 2.005 €

- marinetechnik-nord.de

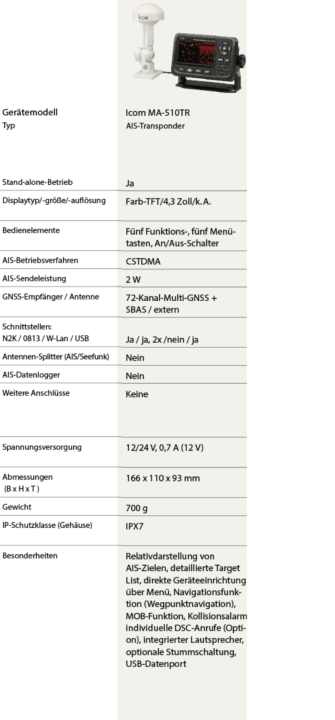

Icom MA-510TR

- Price: 1.080 €

- icomeurope.com

Black box devices

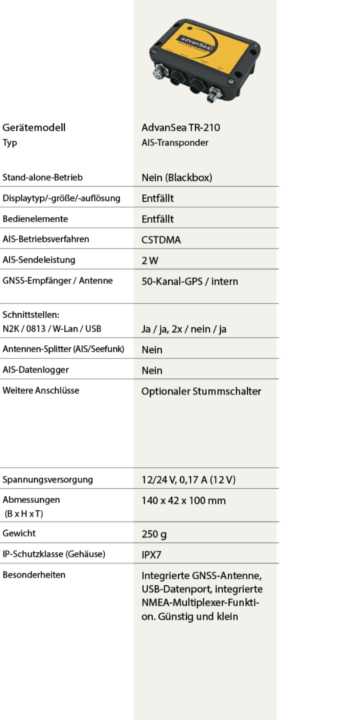

Plastimo AdvanSea TR-210

- Price: 1.211 €

- bukh-bremen.de

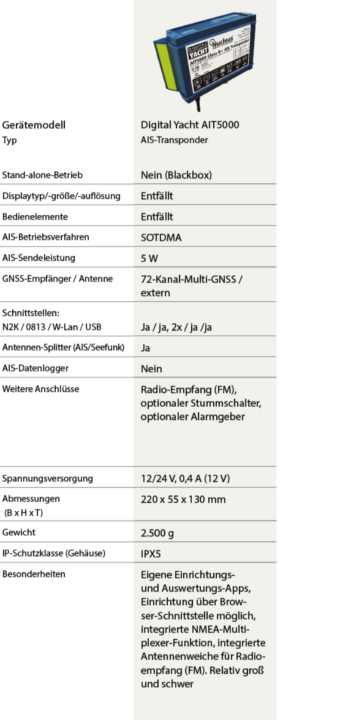

Digital Yacht AIT5000

- Price: 1.848 €

- digitalyacht.com

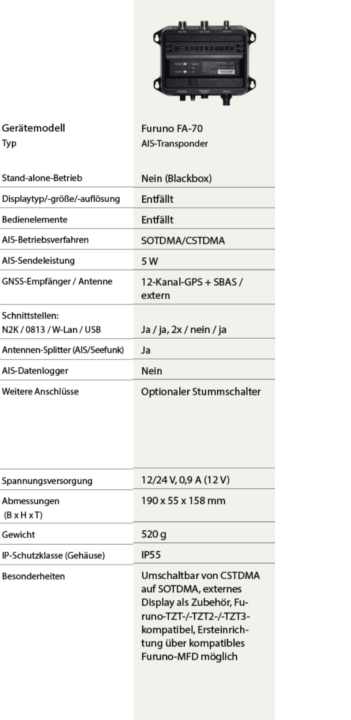

Furuno FA-70

- Price: 1.015 €

- furuno.com

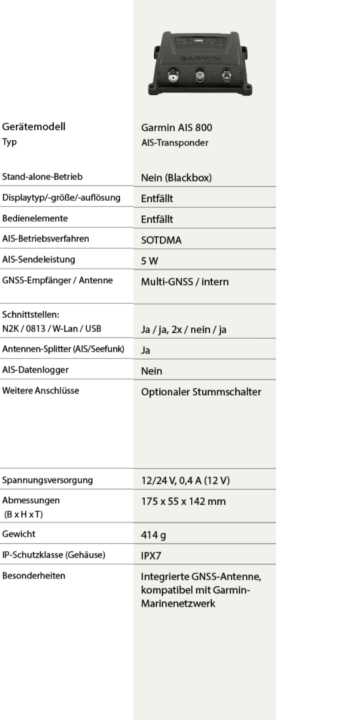

Garmin AIS 800

- Price: 1.049 €

- garmin.com

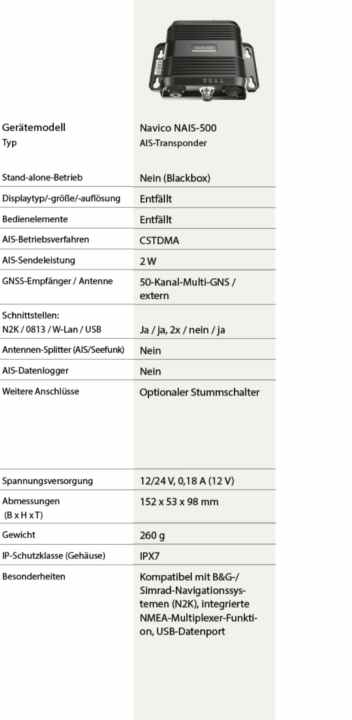

Navico NAIS-500

- Price: 939 €

- simrad-yachting.com

Ocean Signal ABT1

- Price: 1.299 €

- nordwest-funk.de

Raymarine AIS 700

- Price: 1.422 €

- raymarine.com

Watcheye B Pro

- Price: 898 €

- busse-yachtshop.com

Weatherdock easyTRX3 (A20001)

- Price: 1.250 €

- easyais.com

Note: The market overview refers to the current range of yacht-compatible AIS transponders. Products that are currently not available are not included (as of 08/2023)

Installation diagram - how to wire an AIS transponder

Establishing an AIS connection - how it works